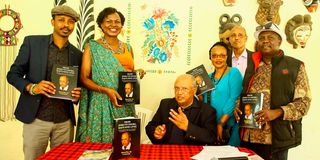

Former Director of Public Prosecutions Sharad Rao autographs his book 'From Jomo to Uhuru, Rao's Nine Lives' at his home in Muthaiga Nairobi on June 15, 2024.

A book by a former long-serving public prosecutor in the State Law Office reveals intrigues during some of Kenya’s most pivotal moments since independence.

Mr Sharad Rao, a lawyer since 1960, worked closely with the country’s first two presidents – Jomo Kenyatta and Daniel arap Moi – given the role he played at the State Law Office.

He also interacted with the third president, Mwai Kibaki – who made him the chairperson of the Judges and Magistrates Vetting Board – and had engagements with Mr Kibaki’s successor, Uhuru Kenyatta.

In From Jomo to Uhuru, Rao’s Nine Lives that was launched in Nairobi on Saturday, June 15, he gives insights into dramatic moments.

For instance, when he was the Director of Public Prosecutions from June 1982 to September 1983, he wanted to peruse files relating to Pio Gama Pinto and Josiah Mwangi Kariuki.

“I asked to see the files to find out who was behind the murders of Pinto and Kariuki, but the authorities concerned came up with excuses and I was never given access to the files,” he says.

Both assassinations were during the Jomo Kenyatta regime, with Pinto’s happening in 1965 and JM Kariuki’s 10 years later.

The role Kenya played in the 1976 Entebbe Raid gets new insights through Mr Rao’s book. He was the assistant DPP, working under Attorney-General Charles Njonjo.

Mr Rao talks of a meeting he attended at Njonjo’s Muthaiga house alongside Police Commissioner Ben Hinga and General Service Unit head Ben Gethi.

While there, he writes, they were addressed by Israeli special forces commando Ehud Barak, who revealed the plans to raid Entebbe airport in Uganda to rescue Israeli hostages. Mr Rao says the president was kept in the dark.

“President Kenyatta was ailing and it was decided not to inform him of the plan, so that he could later rightly claim that he had no knowledge of the arrival of the Israeli planes,” he states.

“Njonjo said, if asked, would deny knowledge of the plan and say they were asked at the last minute for permission to refuel in Nairobi and they agreed as a humanitarian gesture.”

However, Njonjo later informed the president, who reportedly replied: “If something goes wrong, I shall deny knowing anything about it….and if it goes wrong, you and the others will burn your fingers alone.”

Mr Rao was only two months in office as the DPP during the August 1, 1982 botched coup. It is this event that led to a fallout between President Moi and Njonjo.

Former DPP Sharad Rao during the launch of his memoir ‘From Jomo to Uhuru, Rao’s Nine Lives’ at his house in Muthaiga, Nairobi, on June 15, 2024.

Mr Rao reproduces transcripts from some of the hearings during the coup investigations. They show Mr Raila Odinga being forced to write and rewrite statements, apparently because he failed to implicate Njonjo.

“Inspector Mwaniki Muriithi and three other GSU officers visited Odinga in his cell at 11pm. Gethi ordered that Odinga be given pen and paper and told Odinga to write all he knew about the disturbances of August 1, 1982 and his role in it. Odinga then wrote what he called a truthful and detailed account of what he knew. The statement was handed to Gethi who tore it, saying it was rubbish,” Mr Rao writes.

“He ordered that Odinga be given fresh paper to write a ‘proper’ statement. This was repeated four times, with the same result. Odinga said Gethi’s reason for tearing the statements was that he objected to the reference to Njonjo.”

Corridors of justice

The book serves up history about Kenya’s corridors of justice, attempting to show how the independence of judicial officers has evolved. It touches on the 1960 case of Peter Harold Poole, a 28-year-old soldier who was the first and only White person to be hanged in Kenya after being tried in court. He had killed his servant, Kamawe Musunge, who had thrown a stone at one of his dogs that had bitten him.

The book touches on the trial of the Kapenguria Six, revealing that while the lawyers who represented them did so for free, one of them – Achroo Kapila – would demand payment.

Years after becoming president, Jomo Kenyatta allowed the prosecution of Kapila for flouting cash exchange rules.

Mr Rao says the real intention was to get at Kapila for associating with a group that wanted to change the law to prevent Moi from succeeding Jomo Kenyatta.

Mr Rao says he was reluctant about charging Mr Kapila, a member of the Kenyan-Asian community, until a 6am call from Jomo Kenyatta.

Prosecution

“I picked up the phone half asleep but the voice...Instinctively made me jump out of bed and stand to attention. ‘This is Kenyatta,’ he said. There was no mistaking that authoritative tone. He made no mention of my refusal to prosecute. Instead, he continued, ‘I have sanctioned prosecution against Kapila. I will lose faith if the prosecution fails. You have handled major criminal cases and always done a good job. I want you to prosecute this also… I will tell Njonjo that I have ordered you to do so,’” writes Mr Rao.

It also gives a glimpse into the circumstances under which Kenya’s first crop of lawyers operated: Argwings Kodhek (the first African Kenyan to practise law in Nairobi), Njonjo (the second African Kenyan to be called to the Bar after Kodhek), SM Otieno (who caused ripples posthumously due to a burial dispute), Jean Marie Seroney (who presented the Nandi Hills Declaration and became Kenya’s first prisoner of conscience), among others.

The book is not short on humour about the early cases Kenyan courts handled. Mr Rao writes of a lawyer friend of his, Maharaj Bhandari, who was charged for keeping a cow in his compound.

European magistrate

“He appeared before the city court presided over by a European magistrate. My friend and his wife had six children, all girls. They badly wanted a boy, and an Indian astrologer had advised them to keep a cow. They did and the next child born was a boy,” he writes.

“At Bhandari’s request I looked up the by-laws. I discovered that while a ‘bull’ was listed as a prohibited animal within the city boundary there was no mention of ‘cow’. Bhandari defended the case on that basis, arguing that a cow did not fall within the definition of the by-law.”

“The magistrate was not impressed. He said: ‘A bull must include a cow.’ Bhandari countered: ‘Your Honour, you can bully me but I will not be cowed’. The phrase drew headlines the next day. In acquitting him, the magistrate said: ‘No wonder they say the law is an ass’.”

The implied fact in the book is that the Executive has some dread for the Judiciary. Mr Rao says presidents fret about chances of success of cases that go to court, especially on criminal matters.