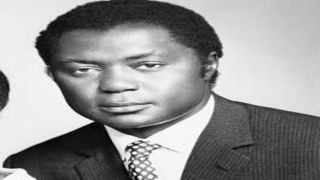

The late Tom Mboya (left) who was gunned down in Nairobi on July 5, 1969.

| File | Nation Media GroupNews

Premium

The obsolete American device and the untold story of Tom Mboya’s death

On the death of Tom Mboya on July 5, 1969, there is the less talked story that was so scandalous that the Western media shied away from it. Even when the matter was brought up in a US congress committee chaired by Senator Edward Kennedy, it appears that no major media outlet picked it up and as such the story of Res-Q-Aire died like Tom Mboya.

While the question on whether Mboya would have survived the gunshot wound is now an exercise in futility, it is important, lest we forget, to put the story of Res-Q-Aire out so that Kenyans can have a better perspective — and perhaps, a closure.

This, however, does not absolve the known and unknown killers of Tom Mboya.

On the day that Mboya was shot, city photographer Mohamed Amin was at his flat on Nairobi’s Mfangano Street when the call came.

“Tom Mboya has been shot,” Amin later recalled the caller saying.

“Location?” he possibly asked.

“Government Road.”

Recording history

Amin picked his camera, a Bolex, and dashed out. Within minutes, he was recording history as an era was coming to an early end. He found Mboya still sprawled on the ground, at the doorstep, but inside Chhani’s Pharmacy on today’s Moi Avenue. The pharmacy was operated by Mr and Mrs Sehmi Chhani – a Mboya family friend. As the ambulance was called, another of Mboya’s friends, Dr Mohamed Rafique Chaudhri, arrived and tried a mouth-to-mouth resuscitation.

Mboya was still breathing when the ambulance arrived with what was thought to be the state-of-the-art resuscitation machine. As Mboya was lifted and fitted into the machine, Amin jumped in and clicked away, while the ambulance sped towards Nairobi Hospital.

If anybody realised the ambulance was fitted with a banned Res-Q-Aire device – then they kept quiet. It was going to embarrass the US government on how a device that had been banned was sold to African countries.

Although the USA’s Food and Drug Administration had found Res-Q-Aire to be ineffective, a shipment of an estimated 10,000 devices found their way into Africa. An FDA report listing the various violations of the ban within the US tends to summarise all that was wrong with Res-Q-Aire.

What we now know of this plastic accordion-shaped resuscitator was that it was a product of Machsa Incorporated and it was being distributed by Crown Products, a division of Chilcote Company. The manufacturer had promised those who bought it that it could provide enough oxygen in an emergency. The label read: “For Every Breathing Difficulty … Res-Q-Aire Emergency Respirator.”

False and misleading

The FDA concluded that “the statement on the carton label, accompanying brochures, and attached card were false and misleading as to the adequacy and effectiveness of the article as a means of resuscitation and for emphysema, asthma, strokes and other therapy; the labelling lacked adequate directions for use, and such could not be written, since the article was neither effective nor safe for its intended purpose; the labelling lacked warnings against use involving obstructions … infants or children where the volume of air would be excessive.”

The FDA had thus ordered the destruction of all Res-Q-Aire products. But how they found their way into Kenya is a mystery.

In the July 1970 issue of Scouting magazine, the scouts were informed that the FDA had found Res-Q-Aire was a “danger to health” and “will not effectively replace mouth-mouth rescue breathing. Therefore, (we) strongly recommend that Scout units discontinue further use of this device.”

While the dumping of Res-Q-Aire had not made it into major newspapers, the death of Tom Mboya would emerge during the Senator Kennedy chaired Committee on Labour and Public Welfare. US Senate records indicate that the matter was raised by Dr Joel Nobel, the director of the Emergency Care Research Institute when he appeared before a congressional committee discussing obsolete medical devices.

Dr Nobel told the committee that so ineffective was Res-Q-Aire that it “would have been banned under even the most casual premarket clearance programs”. But as Dr Nobel said, “10,000 of the units were, reportedly, exported to Africa. Television film clips of the 1969 assassination of Tom Mboya, a major and pro-Western political figure in Kenya, showed futile efforts to resuscitate him with a Res-Q-Aire (device). Whether or not he would have survived with the best of medical attention and equipment is not an issue. If enough people believe that he could have been, and know that the resuscitator was banned in the United States but exported to their country, this, in itself, reflects both on the quality of American medical products, the integrity of the manufacturer, and our own government.”

And Dr Nobel said something that could have led to the silence of Western media on the Res-Q-Aire dumping.

“What are foreign consumers of US-made medical equipment likely to conclude when they learn that they had been sold equipment by a US exporter and a local importer which is considered unsatisfactory for initial use or continued use in the United States?”

It is not clear whether Tom Mboya’s death jolted the Senate to push for the 1973 Medical Device Amendments. But Dr Nobel asked the Kennedy committee not to pass the medical device regulation laws since it would hurt American companies. He also suggested that the FDA should not publicise recalls.

“How widespread is the practice of dumping shoddy American products in foreign countries?” Kennedy asked.

“We have three or four cases that we can point out … but there are diplomatic repercussions on occasion such as the effect – of using a defective American made resuscitator following the assassination of an African political figure.”

The Tom Mboya issue would surface again in the US House of Representatives when Ms Anita Johnson was tabling a report on the continued use of Depo-Provera in Africa – though it was said to cause cervical cancer in women. Again, it had not been approved by FDA. Ms Johnson was an activist from the Environmental Defense Fund, and was testifying against export of Depo Provera at the committee hearings and she said: " The US government should not pay for this unapproved use overseas through its aid programme … If this drug has been determined to be not properly tested for American use, we face Third World accusing us of a double standard in drugs – first-class drugs for Americans and second-class drugs for developing countries.”

“Tom Mboya was shot down in a street in Nairobi a number of years ago. He was what many people consider to be the great promise of democracy in Kenya. American news films showed people bending over Mr Mboya with Res-Q-Aire resuscitator. A Res-Q-Aire resuscitator is an ineffective devise manufactured in the United States … were we involved? Was it our responsibility that that resuscitator was sold to Kenya? I would say we were.”

Looking back, it is hard to know why the Res-Q-Aire saga, especially as it touched on a figure like Tom Mboya did not receive attention.

Koigi’s concern

In Kenya, the only time it was raised was through a comment in Parliament by Koigi wa Wamwere, who had read a tiny article in the Mother Jones magazine, connecting Mboya’s death to the ineffective Res-Q-Aire. Certainly, Koigi, who was moving a Motion on dumping of drugs and medical equipment, did not know about the previous US Senate proceedings.

More so, MPs hardly picked up Koigi’s concern and it is only the Minister for Energy John Okwanyo who released a press statement asking the MP to let Mboya rest in peace. He also called Koigi a “political opportunist”.

That week, Wamwere took to the floor of the House and said that Mboya was “a national leader. Therefore … learning from the circumstances that led to his death is neither opportunistic, criminal nor offensive to his family. It is, in fact, a duty to all of us. It is not fair that the late Tom Mboya’s family should be used as a means of preventing people from speaking the bitter truth about our past and present.”

And that was the only time that Res-Q-Aire was ever discussed in Kenya. How a banned equipment found its way to Kenya and who was involved was never resolved. How many other people may have died due to the use of such a defective device is not known.

But that a banned device was sold to Kenya and used in a futile attempt to resuscitate Tom Mboya has been one of the stories that few want to talk about. It was the American scandal on Mboya’s death. It is our scandal, too.

@johnkamau1