Premium

Why bandits won’t stand down in the North Rift

Security troops readying for an operation to flush out armed bandits from Malaso escarpments in Samburu County.

What you need to know:

- As widows and orphaned children bear the scars inflicted by armed raiders, who will heed their cry?

- Did they deserve to die?

Attacks by bandits are often reduced into mere statistics by various reporting agencies, completely masking the faces whose lives ended so brutally.

From politicians to security officers, peace activists, teachers, businessmen, villagers and school children, many have fallen victim to banditry. No group is unaffected.

In Kerio Valley (Elgeyo Marakwet), West Pokot, Baringo, Laikipia, Turkana and Samburu counties, banditry has caused untold suffering, with numerous deaths and injury.

Drought, that often triggers cattle rustling and banditry, compounds the situation in areas like Samburu, Baringo, and other Northern Kenya counties.

Despite successive government interventions, the situation persists, resulting in violent displacement, disrupted livelihoods, and a sense of hopelessness. Schools and other learning institutions are often forced to close, further impacting the affected communities.

The recent killing of Paul Leshimpiro, the Angata Nanyekie Member of County Assembly, on February 25, in Samburu North, has once again highlighted the rising insecurity in the region.

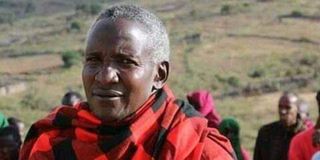

Late Paul Leshimpiro, Angata Nanyekie, Member of County Assembly.

Leshimpiro, a vocal advocate for peace, had pleaded with President William Ruto to personally intervene to put an end to the deadly bandit forays just days before his tragic death.

“Which special person will die for you to take action against banditry? Mr President, have bandits overpowered you? Are your forces less armed than bandits?” Mr Leshimpiro posed on January 29, during the burial of a police reservist in Morijo area, in his ward.

The government’s failure to protect innocent citizens in Samburu, Baringo and Laikipia counties has sparked outrage among leaders.

Samburu Senator Steve Lelegwe and MP Eli Letipila mourned Leshimpiro emphasising the devastating impact of banditry on the ground.

“The government has failed to protect its people. The military has not had any impact. In fact, their deployment has led to the displacement of many families and livelihoods have been disrupted,” Dr Lelegwe said.

“The impact of banditry on the ground is devastating. Homes and businesses have been destroyed, schools closed and people have fled their homes to settle in temporary camps. It is sad to see their leader laid out in mortuary (by the very malady he fought),” he added.

Residents have petitioned the Senate to address the rampant bandit activity in Samburu West, and highlighted the number of deaths and injuries caused by the attacks.

“What will we do since the government has failed, leaving our souls to bleed for every loss?” Mr Letipila posed on Sunday.

Three days ago, a man and his three-year-old son were killed by suspected bandits in Lolmolog village, Samburu.

The Suguta Valley's unique landscape which is now attracting tourists in Samburu North.

On February 10, a blind primary school head teacher was shot dead by bandits at Ngaratuko area in Baringo County.

And on January 25, suspected bandits pumped 15 bullets into Laikipia-based rancher Lucy Wambui Jennings’ car, leaving her to nurse gunshot wounds on her head and arm.

Ever since she moved into her 4,000-acre ranch in Rumuruti in the 1970s, it has been invaded by illegal grazers several times.

Just like the nearby Laikipia Ranching Conservancy and Mugie Ranch, Ms Jennings has suffered for years at the hands of illegal grazers.

She fled for her life after bandits raided the ranch in 2010 and drove away with 400 cattle.

Four years ago Ms Jennings’ chief security officer, Joseph Lokurchan, was also shot dead by bandits who drove away with 30 cattle.

To date, hundreds of people have been killed in a span of one year, in various parts of the insecurity prone parts of North Rift, even after deployment of military troops in the region.

The daring broad-daylight attacks have now become a routine in the region, despite intensified security operations by the police, who are backed by military soldiers.

In Samburu for instance, bandits always take advantage of the bushy areas along the roads, from where they hide and lay ambush on security and passenger vehicles plying the road.

Whenever gun-toting groups stage attacks, they often retreat into bushy, rocky areas, making it impossible for security troops to trace them.

Security troops readying for an operation to flush out armed bandits from Malaso escarpments in Samburu.

The Baragoi-Maralal road, where the MCA was killed, is mostly rocky and rugged, and most parts are not covered by mobile communication networks. These terrain seems to work to the bandits’ advantage.

Attackers have also reportedly turned Malaso Valley into their ‘operation territory’ as they continue to stage raids across Samburu West.

The edges of the Rift Valley connecting these ravines and gorges is hard to access as the land surface consists of sharp, rocky and mountainous relief, populated with thorny shrubs and cacti.

Recently, Samburu West residents petitioned the Senate to intervene and address rampant banditry activity in Malaso and Lorroki divisions.

It still remains unknown what the government is planning to do to address the deteriorating situation in the North Rift. Bandits are brazen enough to attack even in the presence of a military contingent operating in the hotspots.

From the bandit-prone Mukutani village on the border of Baringo South and Tiaty sub-counties to Pura in Samburu West, Baragoi in Samburu North, Kerio Valley in Elgeyo Marakwet, Lodwar in Turkana and parts of West Pokot, many women have been widowed and children orphaned by killer bandits.

The in the insecurity-prone areas are evident as most families have been impoverished following constant theft of livestock and killing of home-guards by bandits since February last year.