Premium

“Even in Mathare, people have a right to life”

When Victoria Wambui agreed to meet me at the offices of the Mathare Social Justice Centre, I pictured a sad, craven woman, wearing her pain on her face.

But when we meet, she is lively and matter-of-fact. She closed her business today, she tells us, because we were coming. She speaks in an easy Sheng, although like many here, her command of English is better than she lets on.

“I sell michugi (chicken heads),” she tells me. “It has good profits here in Mathare."

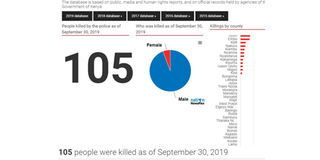

Newsplex, the data journalism project of the Nation Media Group, has been looking into police killings. Mathare, in particular has come under scrutiny for the number of people killed by police. According to the Mathare Social Justice Centre, up to 80 people have been killed in Mathare this year, though many cases are difficult to document properly.

Human rights groups in Mathare complain that police often kill people who are often unarmed and pose no risk, or who have surrendered and can easily be arrested.

Newsplex has come to Mathare to report on a tragedy that happened here nearly three years ago in which three men were shot dead by police, even if people here say, only one was being pursued. Only Victoria, who was sitting with them that day, survived.

On October 17, 2013, she did not open her business as she usually did. Instead, she went to her four-year-old son’s school, to settle his kindergarten fees. She remembers it was a Thursday.

FRESH START

Then she accompanied her ex-boyfriend to a chemist she knew; he had been feeling unwell. Brian Wachika or Brayo, went by the name “Ombiji Live” on Facebook, and their relationship had ended in 2006. Victoria admits Brayo alikuwa anaenda round, which is sheng for being a thief.

But she says, he had made a fresh start, gotten married, moved to Kayole and opened a shop there. His mother and sisters still lived in Mathare though, and Victoria thinks he had come back that day to visit them.

She was at home when Brayo called again. He wanted her to join him at the “base”, where he was sitting with his friends. When she joined him, she found two other men.

Silas Muthini, or Sila, worked as a carrier in Eastleigh, earning about Sh20 per load. He and Victoria had grown up on the same plot, and he was about three years older than her. He was a member of many community groups in Mathare, including an artistic peace initiative called Stop the Bullets, founded after post-election violence had rocked Mathare in 2007.

His Facebook timeline, which is still up, shows a fun-loving person, posing in soccer shirts, and enjoying himself at the beach. Victoria recalls that when he joined them that day at around 2:30pm, he told her business had been scarce and he had only made Sh180.

“Tito” was the third man. People we spoke to say Tito, whose real name Newsplex still does not know, had served time in prison. Moreover, he had lapsed back into crime after his release, and the police were hunting for him.

“Tito had moved here recently, but Brayo and Sila were our friends from before. Brayo had asked me to come and chill with the boys, which was a normal thing. I went, and we talked for long, from twelve, one, two and three.”

It was around four when everything changed. “I heard, to my shock, guns being cocked,” she says. Because she was seated on a stool at an angle to the three men, she saw the three policemen before they did. They were wearing kabuti za maziwa (dairy overalls), carrying pistols.

“Tito alikuja kama ameshikwa hapa na polisi mmoja, akachapwa ya kichwa. (Tito was grabbed here by one policeman, and shot in the head),” she says, holding her neck and making a shooting motion to her forehead with her left hand.

“Sila was shot here. Brayo was shot here too,” she says, pointing to her back.

Tito had died instantly but Brayo and Sila were still alive. Desperate and wounded, they fled towards a nearby gate which opened onto a staircase and safety, but Sila never made it. “Sila was shot twice and died there, as he entered that gate. He died on the spot.”

Brayo had also been shot twice at the gate, but more muscular than the rest, he could still move and made it up the stairs, onto the unfinished third storey.

Hearing the police behind him, Brayo jumped onto a house below, plunging through the iron sheet roof. His pursuer, guessing correctly that he would be too stunned from the fall to flee, ran down the stairs and found him in the house. “He came round, entered that house and found Brayo. He was not dead. He shot him between the eyes and another one here. He was shot nearly five times,” she says, pointing to the side of her neck.

His body was moved out. All this time Victoria, still untouched, sat watching, stunned. “I was still sitting there. No-one said anything to me. I did not move. I was in shock, just watching everything happen,” she said.

By that evening, news of their deaths had spread on social media. At 10pm, Dennoh Muatha M, commented on Brayo’s profile picture on Facebook: “ombiji joh!!!!!!! i have lost a brother”, Thirteen minutes later Klyrico Hassan wrote on Sila’s Facebook wall: “woie jo....Silas..hina kaa maneo... mola akulaze mahali pema....”

Victoria looks away, her eyes welling up. “I am very grateful to God that I am a woman, because had I not been a woman, I would have died. It’s as if they had been told, these people are here, they’ve been here for this long, and there’s three men and one woman. So there were three policemen, and each shot his person.”

PLANTED KNIFE

She is adamant that none of the three men were armed and says, she saw police plant weapons on them. “Sorry to say this, sijui kama itanihappenia vibaya. (I don’t know if something bad will happen to me). Each of them had a weapon planted on them by police).”

She suspects the police plant weapons on the suspects they kill because they are asked to account for the killings by their superiors.

“Sila aliwekelewa kisu (They planted a knife on Sila),” she says her voice taking on an urgent tone. “He didn’t have it, by the way, he didn’t have it. Brayo had that little pistol planted on him, but he didn’t have it. I cannot speak for them and say they weren’t armed, but I saw, I saw with my own eyes, those weapons being planted. So that really hurts”.

Human rights groups in Mathare complain that police often kill people who are often unarmed and pose no risk, or who have surrendered and can easily be arrested.

“But I would say, just to be honest, they should have been ordered to surrender, because we were seated. There was nowhere anyone could have run to, no escape route. If you’re ordered to surrender at gunpoint, you know, you comply since you can’t escape.”

Victoria’s voice rises. “I don’t deny that young men in Mathare steal. They do, but they also have a right to life. Every person has a right to his life. The police haven’t found you at the scene of a crime, they found you just sitting down,” she says, leaning back to demonstrate. “They should tell you to surrender, you will surrender. If you resist then maybe something might happen. But mtu apewe tu hiyo haki yake,Mathare (But just give us that right to live, here in Mathare).”

Residents in Mathare know their rights, but poverty limits their options. “Mothers here in Mathare don’t have the money to hire a lawyer. We can’t a hire a lawyer to prosecute the policemen who shot these people,” she says. She adds that Sila’s brother had begun following his case up, but then stopped. The whole thing went quiet.

“Can you imagine? Someone working for Sh180 a day has been killed, because he sat near someone the police were looking for. He was not a bad person.” Nothing was done for Tito and Brayo either.

Many people might ask what an innocent person would be doing with criminals. Victoria says she did not know Tito well, but heard he had been jailed for 10 years. After his release, it was clear he had not reformed; he was stealing, kidnapping and carjacking. “Hapa tu, alikuwa anahijack gari (Just here, he used to do carjackings),” she says, pointing towards Juja Road.

In the slums, she says, it is not always possible to avoid people you know are breaking the law. “If someone is your friend, he may be doing wrong things, but you can’t chase him away. Maybe they had come to speak about how he could leave crime. He’s your friend, and you’re seated there talking.”

Victoria is demanding that police apply the law equally regardless of social class. “But I keep saying this, I don’t think in Kileleshwa people are shot this way, or in Runda. We should also have our rights. Vijana wapewe hiyo right ya kuishi. ”

Arrest him. Take him to jail for five or six years. Maybe he’ll come back changed. Maybe he won’t, but he’ll learn something. He’ll learn why was he was imprisoned, so when he comes back down here, he’ll know he shouldn’t do this and this and this. Maybe he can start a business, join a group, anything. He can change.”

I ask her if she knows the policemen who shot the three. “Yes, we know them. But what can you do? You can’t shout louder than the government. Si serikali ndiyo kila kitu? Sorry to say this, but of you point out a policeman, your life is over. Your life ends there."