The 1988 Seoul Olympics 5,000 metres champion John Ngugi.

On a hot and humid evening on October 1, 1988, at the Seoul Olympics Stadium in South Korea, John Ngugi of Kenya earned the title of ‘King John I’.

Ngugi won the 5000 metres gold medal for Kenya to cap an extraordinary Olympics which saw the country finish first in Africa, and 13th overall with nine medals (five gold, two silver, and two bronze).

Paul Ereng (800m), Peter Rono (1500m), and Julius Kariuki (3,000m steeplechase) won Kenya’s other gold medals from athletics. Welterweight boxer, the late Robert Wangila, also made history as the first African boxer to win a gold medal in the Olympic Games when he triumphed in the welterweight category.

Ngugi, who was born in Kigumo in Murang’a County, before his family later relocated to Nyahururu, went to Seoul as a three-time World Cross Country champion, as well as the 1987 African Games 5000m and 1985 African Championships 1500 winner, soon after joining the Armed Forces.

President Uhuru Kenyatta (right) meets with heroes and heroines during the celebrations of Kenya @50 at at State House, Nairobi on December 12, 2013. Pictured from left: David Okeyo, Kipchoge Keino, Tegla Loroupe and John Ngugi. President Uhuru later gave the group a flag to take to Mt. Kenya where Ngugi later took the flag to the then Nyeri Governor Nderitu Gachagua and both joined others to plant trees in Mt. Kenya.

It is from this background that Ngugi admits that he is a person of interest in the Paris Olympics, especially, on August 7 when the heats for men’s 5000m will be held, followed by the final on August 10 at Stade de France.

Nation Sport caught up with Ngugi in the company of his friends, former rally driver Patrick Njiru, and John Gachau on Friday at his Kitengela residence resting, after a week-long stay in hospital where he had been admitted on Wednesday following a road accident.

“I am fine now, thanks to the care and financial assistance I received from Athletics Kenya, who also footed my medical bill,” the five-time World Cross Country champion said.

“I almost expired, but thank God I will be able to watch the 5000m. I hope Kenya will win it. It is not difficult,” the father of two boys added.

Lotto Chief Executive Officer Joan Mwaura (centre) with two five times World Cross Country champions John Ngugi (left) and Paul Tergat during Athletics Kenya 70th Anniversary celebrations at Nyayo National Stadium in Nairobi on December 15, 2020.

"My advice to our teams is just train hard, run easy and the gold is yours," said Ngugi, 62.

Kenya will be represented by the World 5000m bronze medallist, Jacob Krop, national trials winner Ronald Kwemoi, and Edwin Kurgat, who are rookies, but the best prospects of medals, according to Ngugi.

The trio was not born when Ngugi was making history, but he said they are on the right side of history and should run as a team.

They will face stiff opposition from Ugandans, Ethiopians, and Norwegians. Olympics champion Joshua Cheptegei of Uganda is eyeing his second gold after his exploits in Tokyo three years ago.

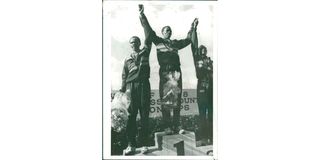

A worthy example to emulate: John Ngugi (centre) raises the arm of compatriots Paul Kipkoech (right) and Kipsubai Koskei after the trio took the top three positions in the 1988 World Cross-Country Championships.

He will hope to follow in the footsteps of Finnish Lasse Viren (1972 and 1976) and Briton Mo Farah (2012 and 2016), as the third man in history to win back-to-back Olympic golds in the distance.

The Ethiopian charge is led by 2016 bronze medallist, Hagos Gebrhiwet, the second fastest man over the distance with a personal best time of 12 minutes and 36:73 seconds, hoping to emulate compatriots Miruts Yifter (1980), Million Wolde (2000) and Kenenisa Bekele (2008). World 5000m champion Jakob Ingebrigtsen of Norway will also have a say in the 12-and-a-half lap race.

Ngugi intimated that the Kenyans can borrow a leaf from his game plan.

Ngugi recalls the disappointment of missing out on gold at the 1987 World Athletics Championships in Rome, spurned him to gold in Seoul. Poor finishing cost him victory which was within his grasp.

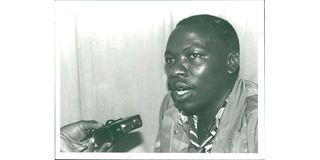

In this undated file photo, John Ngugi, the five-time world cross-country champion and former Olympic 5,000 metres champion, speaks after being allowed to compete again after the International Amateur Athletics Federation (IAAF) lifted their four-year ban on him. The ban was imposed 27 months ago after Ngugi refused to take a random dope test in his rural home of Nyahururu in February 1992, saying the IAAF test team had not properly identified itself and was not accompanied.

Due to his cross-country reputation, Ngugi caused considerable surprise when he won his 5000m heat in Rome in a new championship record of 13 minutes and 22.68 seconds.

He lined up at the start of the final as the hot favourite, who had won the African Games gold at home, and the World Cross Country title in Christchurch, New Zealand.

But this final went wrong. Ngugi took the lead during the second kilometre and started to push the pace. Despite his front running tactics, he was unable to establish a break on the field, and when the sprint for home started just before the bell, Ngugi was overwhelmed, dropping from 1st to 9th in the space of 200 metres, and eventually fading to a 12th place at the finish.

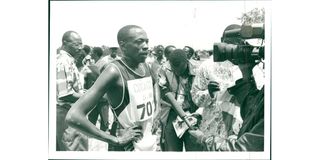

John Ngugi is interviewed after the senior men's race during the National Cross-Country Championship at the Ngong Racecourse on Feb 17, 1996. Ngugi finished 96th out of 261 athletes but officials and athletes described his performance as promising.

This result made Ngugi change his training tactics, especially at the Kasarani Training camp, where he had secretly drawn his training regime running parallel with what head coach Mike Kosgei had prepared before the 1988 Olympics.

"I used to train secretly at night alone, sneaked back to camp, and joined the rest for the official programme," said Ngugi.

This training and painful experience of Rome prepared a different Ngugi who stunned the world in Seoul.

In an attempt to counter the finishing sprints that had let him down in Rome, Ngugi said that he had to try a new, different, and courageous tactic in Seoul.

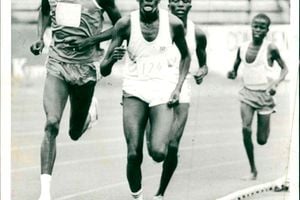

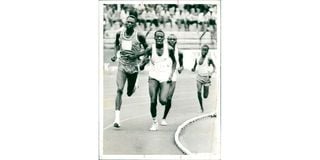

John Ngugi (right) leads Moses Tanui in a local race on June 17, 1988.

Just before the pack reached the 1km in a respectable 2min and 42.8 seconds, Ngugi moved up quickly from the rear of the field, took the lead, and then sped through the next kilometre in an extraordinary 2 minutes and 32.2 seconds.

Not surprisingly, no one else decided to follow this seemingly suicide pace, and by the end of 2km, Ngugi had a 50m lead.

Ngugi maintained this lead during the ensuing laps, and although his lead was reduced when the expected sprints came in the last lap, he still had enough left in the tank to lope through a final lap of 60.8 seconds to win by 30 metres in the year's fastest time of 13 minutes and 11.70 seconds.

He did the same in the 1992 Boston World Cross Country Championship, under snowing and cold conditions, before failing to qualify for the Barcelona Olympics later that year.

Ngugi's career came to a disappointing end on February 18, 1993, at only 31 after he was barred from competing in the Kenya National Cross Country Championships for failing to take an out-of-competition dope test willingly, forcing doping officials of the International Amateur Athletics Federation (now World Athletics) to impose an automatic four years suspension.

The Kenya athletics fraternity appealed to the IAAF, which lifted the suspension after 23 months.