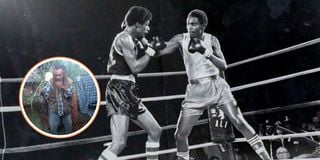

Peter Kamau Wanyoike (right) fights Denis Armstrong of the United States during the Muhammad Ali Boxing team when Kenyan boxers toured the US in 1980. Inset: Wanyoike at his home in Kiambu County.

The saying, “It’s not the size of the dog in the fight, it’s the size of the fight in the dog” which is often credited to American writer Mark Twain and former US president Dwight D. Eisenhower could as well have been aimed at Peter Kamau “Pipino” Wanyoike, one of Kenya’s most accomplished boxers who now lives in obscurity at his Komothai home in Kiambu County.

“Pipino” Wanyoike ranks as high up as Philip Waruinge, Stephen Muchoki, Robert Wangila, and Ibrahim “ Surf” Bilali in Kenyan boxing, yet he lives in obscurity despite having accomplished so much for the country.

Wanyoike’s simplicity can easily deceive anybody, especially those who thrive in criminal activities especially at night. Kamau has been a victim, but he often ensures he turns tables on his attackers, leaving them battered, bruised and helpless, thanks to his boxing experience. He believes former boxers should take charge of their destiny by doing a lot in their active years so as to secure their future in retirement.

The retired welterweight boxer worked for Kenya Prisons Service from 1975 to 2009 when he retired as a senior sergeant. After 34 years at Kenya Prisons Service, he let his hair grow unrestricted into dreadlocks.

For 34 years, he was a member of Kenya Prisons Boxing Club, one of the top boxing clubs in Kenya. His father, the late George Wanyoike Kamau, was a prisons officer who had encouraged him to participate in boxing from way back in 1970 when the young Wanyoike was in Class Seven at Lang’ata Road Primary School in Nairobi.

His father realised he had talent after he won in the bantamweight category (54 kilograms) in Kenya Junior Boxing Championship at Pumwani Social Hall, Nairobi.

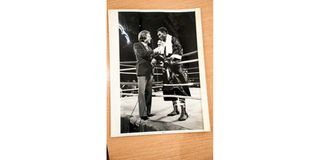

Kenyan boxer Peter Kamau ‘Pipino’Wanyoike (right) is congratulated by NBC commentator in April 1980 after fighting American boxer Denis Armstrong in Washington.

He went on winning fights till he joined Jamhuri High School in Nairobi, where he sat his Form Four exams in 1974. In all his boxing career in Kenya, he represented Kenya Prisons Boxing Club. As a Form Two student, he had already won Kenya Junior Bantamweight boxing title.

The media publicity he received earned him a lot of respect from other students, and at the same time kept him from quarrels, although he was generally humble.

In 1975, Wanyoike joined Kenya Prisons Service as a recruit, his experience in boxing being an added advantage. At Kenya Prisons Service, he competed against other boxers in bantamweight category, and qualified to join Kenya Prisons Amateur Boxing Club, the top amateur boxing club in Kenya, having beaten other reputable boxing clubs as Kenya Breweries, Armed Forces, among others.

Wanyoike’s first and only loss to a Kenyan boxer was as a light-welterweight against Philip Mathenge, who had joined the Armed Forces Boxing Club from Kenya Prisons Service. Kamau had beaten Mathenge twice, and his loss at Desai Memorial Hall in Nairobi was met with a lot of booing from fans who believed he had won convincingly.

Wanyoike says there are times when boxers encounter bad moments, but that should not deter them from aiming higher. He recalls the day he missed a medal at the 1984 Commonwealth Games in Melbourne, Australia.

He had qualified for 1984 Los Angeles Olympic Games but failed to enter the ring for his opening bout following a jaw injury during a spurring session. Kenya was among the countries that had supported the USA-led boycott of the 1980 Moscow Olympic Games.

To reciprocate, USA sponsored a major boxing tournament in Nairobi where many countries that had boycotted the Moscow Olympic Games, took part. Kamau represented Kenya, and fought Don Carry of USA in the welterweight final at Kenyatta International Convention Centre (KICC).

Kamau lost narrowly and won Kenya a silver medal. That was the only loss he had suffered against an American. Carry later turned professional and became World Welterweight Boxing champion.

Wanyoike was born in 1957 at Kiganjo Police Training College in Nyeri, where his father, George Wanyoike Kamau, worked a police officer and a sportsman of rare combination talents in various sports.

The Kenya Olympic Association Handbook for The XVIth Olympiad in Melbourne, Australia, 1956, describes Wanyoike Kamau G. as “A police officer aged 32, a Kikuyu born in Kenya, married with 3 children, had represented Kenya since 1948 at 880 and later 440 yards at Inter-Territorial and Indian Ocean Games.

Some of the medals retired Kenyan boxer Peter Kamau Wanyoike won during his boxing career.

He had also boxed for Kenya, and took part in 400 metres and 4x 400 metres relay. He later left the police and joined the prison service..”

Wanyoike is estimated to have fought about 350 bouts since the early days in primary school before retiring from boxing in 1988. He retired in 2009 as a senior sergeant after serving the Prisons for 34 years, and is married to Lucy Wangari.

They are blessed with three children - two boys and a girl, all grown ups. Steve Kamau Wanyoike, 30, lives in Germany with his family, Shirlene Wanjiru, 22, works in West Pokok while Ian Wanyoike, 20, works in Nairobi.

On the status of local amateur boxing, Kamau says boxers should put more effort in building their careers without relying much on the officials running the sport. He says officials mostly ride on boxers’ personal effort without caring about the boxer’s welfare.

“Even as you show respect to the officials and coaches, tune your mind and sharpen your skill knowing that only those who are impressed with your effort during your international fights can help you turn professional to better your life. No official will come to you to ask what kind of help you need to make you do better,” he says.

Kenya’s “Hit Squad” that dominated amateur boxing and made Kenya be among the best in the world is now hardly remembered.

Wanyoike says that although economic pressure has affected many institutions where some upcoming boxers would be employed, many are left wondering how to survive after training. The focus is more on survival. Without employment, boxers have struggled perform the way they would like to.

Wanyoike engages in farming to survive. He grows a variety of crops such as avocados, bananas, maize, beans and vegetables. He also rears chicken. His farm is not big, but it keeps him busy.

“Do the best you can with what you have. Don’t rely on anybody for your survival. It is between you and your God. Those who feel you are worthy of recognition, let them do what they feel is better for you, but let your record speak for you,” he says.

At some point in Wanyoike’s boxing career, Boxing Illustrated, American magazine which used to be an authority in boxing and was regarded the bible of the sport, placed eight Kenyans among the top ten best amateurs in the world.

They were led by Kenya’s captain, southpaw Wanyoike who had won gold medal in the prestigious Thailand King’s Cup three successive times.

kiboihenry2@gmail.com