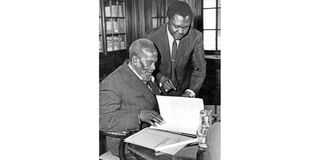

Jomo Kenyatta (left) and Tom Mboya attend the Lancaster House Conference in London.

In 1970, as economic discontent and tribal animosity heightened just a year after the assassination of Tom Mboya, Joseph Daniel Owino, alongside many others, capitalised on the situation to plan a coup against the government of Mzee Jomo Kenyatta.

However, all the plotters were arrested, tried and jailed for periods between seven and 10 years after their plan leaked.

Delivering his sentence before a packed court, Magistrate SK Sachdeva described Owino as “the brain of this infamous conspiracy”.

Mzee Jomo Kenyatta and Tom Mboya share a joke at the 1962 independence conference in London.

During his interrogation, Owino had revealed every detail of the plot and implicated senior government figures such as Chief Justice Kitili Mwendwa and military chief General Joseph Ndolo, among many others.

The statements and confessions collected from plotters had also mentioned him as the key planner. After serving his nine-year prison term, Owino fled to London where he remained until his death in 2012.

According to recently declassified files seen by The Weekly Review, Owino, while living in London, wrote a letter to the British Minister for Overseas Development in which he claimed his woes began in 1969 after the government realised that he knew “everything about the conspiracy to kill Tom Mboya”, and also knew the killers.

“Mr Mboya knew before he was killed that there was a clique around President Kenyatta who were plotting to kill him and (Mboya) had decided to employ me as his professional bodyguard,” Owino wrote.

He went on to inform the British Minister that a Catholic priest who had witnessed Mboya’s murder was deported while himself and other friends who had details about the assassins were arrested.

“After his death, when the authorities learned that we, the four of us, Mboya’s friends and supporters had seen the priest, and probably knew everything about the conspiracy to kill Mr Mboya, the Catholic priest was immediately arrested and deported… (and) three of my friends were rounded up and shot.”

But just how true were Owino’s allegations? For starters, Owino joined the military in 1956 and was assigned to the East African Education Corps as a clerk.

President Jomo Kenyatta (left) with Kanu secretary-general Tom Mboya after a three-hour National Executive Committee meeting at State House, Nairobi. The meeting was also attended by all provincial Kanu vice-presidents and vice-president Daniel arap Moi.

In 1962, in a bid to Africanise the military as Kenya geared towards independence, he was sent for further training at Lanet, promoted to a Lieutenant, and posted back to Lanet as an instructor.

That same year, he was accused of breaking military discipline by inciting junior soldiers to rebel against their white commanders. To avert rebellion, the military leadership transferred Owino to Kahawa, but just three days after his posting, junior soldiers at Lanet mutinied, demanding his return. The colonial government acted quickly by crushing the mutiny and arresting all the rebelling soldiers.

From Templer Barracks Kahawa where he was based, Owino continued to communicate secretly with the imprisoned soldiers, encouraging them while at the same time praising them.

In one letter, dated March 1963, he wrote: “I saw Mr Mboya and your beating stopped yesterday. Mr Mboya promised me that he will do everything he can to help you so do not worry.” This letter indicates his earliest connection with Mboya if indeed his claims were true.

President Jomo Kenyatta, Tanzania President Julius Nyerere and Tom Mboya engage in a light banter at the Nairobi Airport on March 30, 1968. Tom Mboya was assassinated on July 5, 1969.

This letter was secretly delivered by Lieutenant JB Nyagah. Nevertheless, the military saw Owino and Nyagah’s action as a serious breach of military discipline, especially from serving military officers.

They were subsequently arrested, court-martialed, dismissed from the military and sentenced to seven years in prison. Luckily for them, independence was just around the corner and they didn’t serve their full prison terms for they were among prisoners pardoned by the new Prime Minister Jomo Kenyatta, who would later become the founding President.

Owino would later get a job as an assistant District Officer, but this was short-lived for he was arrested and jailed from 1965 to 1968 on allegations of forging an official document.

According to Owino’s secret letter to the British Minister, in 1969, Mboya, who was concerned about his life, hired him as his professional bodyguard owing to his military background.

Again, did Owino really serve as Mboya’s professional bodyguard? While Ouma Nisa was Mboya’s known bodyguard, some of Mboya’s American friends had actually advised him to hire a professional bodyguard after they became concerned about his life.

This could be confirmed from an interview given by Mboya’s American friend Frank Montero in July 1969. In March 1969 Just four months before his assassination, Mboya visited New York to attend a United Nations conference, and confided in some of his friends about the danger towards his life. The meeting took place in the house of Robert Gabor on Long Island, New York.

Frank Montero claimed they asked Mboya whether his bodyguard, Ouma Nisa, was competent, but he replied that he wasn’t and that he needed $120 to hire a professional one.

They immediately agreed to raise money amongst themselves to enable him to hire a professional bodyguard. Even though it is not certain whether Mboya went on to hire a professional bodyguard, there could be some truth in Owino’s claims that Mboya hired him as a professional bodyguard on June 15, 1969.

This is based on the fact that it was just three months after Mboya’s friends agreed to raise money to enable him hire a professional bodyguard. Adding to the twist was the arrest of Owino on security grounds just after the assassination of Mboya.

Addressing this in his letter, Owino wrote that after the assassination and after the government became aware that he knew the killers, “three people came in my house and shot me leaving me for dead, I lost one of my kidneys; eventually I was arrested, brutally tortured and later imprisoned”.

He remained in detention until 1970 when he was released. Just after his release, he became a central figure in the 1971 coup plot which had a very strong Mboya element.

It did not only implicate Mboya’s widow, Pamela, but also many of his friends, some of whom had worked with him in politics and trade unionism from as early as 1955.

They included Gideon Mutiso, Oyangi Mbaja, Dennis Akumu, Jesse Mwangi Gachago. Also mentioned was Irving Browne an American trade unionist, and a long-time friend of Mboya who had funded his activities in 1950s.

The plotters had approached him for funds but he never gave any commitment.

One surprising thing is that despite his prominent role in the coup plot, Owino conveniently avoided mentioning this in his letter to the British Minister. Instead, he only talked about his imprisonment from 1971 to 1980. According to him after being held in solitary confinement for all those years, he was allowed to seek further treatment in Britain in 1981.

This was only granted after he made an undertaking that he wouldn’t engage in politics during his stay in Britain. He wrote: “Two of my friends, Dr Robert Ouko, Minister for Foreign Affairs and Mr Kitili Mwendwa, Kenya’s first chief justice, guaranteed in writing to President Daniel arap Moi, that while in Britain attending medical treatment I will not involve in any activities against the Kenya government.”

“Both of them have since been killed, but saved my life by advising me to apply for political asylum and I owe them a debt of gratitude,” Owino wrote.

Owino claims, although startling, should also be taken with a pinch of salt for he could have exaggerated them to attract British sympathy and support as he sought to return to Kenya to vie for a political seat in the 1992 multiparty election.

In this regard he had informed the minister, “As a political refugee. I have approached the UNHCR’s representative in the UK for help to enable me return to Kenya, they offered to give me a return air ticket to Kenya plus £80 repatriation allowance, but advised me to seek help from the British government on: a valid Kenyan passport, some guarantee that Kenya authorities wouldn’t arrest me on arrival and financial support to help me settle in Kenya.”

On the latter issue he explained: “I have been technically outside Kenya over the last 22 years and need a temporary support while I look for other alternatives.”

Owino died in 2012 in London where he was also buried.