Uganda President Idi Amin is welcomed by President Jomo Kenyatta when he visited the country in the 1970s.

On July 4, 1976, immediately after Israeli war planes cruised into the Kenyan airspace after a daring rescue operation in Entebbe, Uganda, the then US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger sent a message of appreciation to Mzee Jomo Kenyatta for Kenya’s role in the operation.

US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger gives a speech at his arrival at the Orly airport, on September 6, 1976 for an official visit in France.

Kissinger was very forthright in his instructions to the US Ambassador who was to deliver the message. He had to deliver the message personally to Mzee Kenyatta and in case the president was not around, to a senior government official who had the president’s “absolute confidence.”

“You should immediately get the following oral message to Kenyatta personally, and if that is not feasible, to Koinange or possibly Njonjo, whoever has Kenyatta’s absolute confidence and was probably involved in Israel operations,” Kissinger instructed, according to documents declassified by the US State Department.

Just before the rescue operation, the National Security Council, in a memorandum to the US President’s Assistant for National Security Affairs, had advised that Kenya risked being attacked by Amin if its role in the operation was to be known. This almost turned out to be the case when Amin, on learning that the Israeli war planes had refuelled in Nairobi, began making plans to invade Kenya.

The American spy agency, CIA, which was closely monitoring activities in Uganda, reported receiving credible information that Amin had approached President Julius Nyerere of Tanzania to request him not to intervene if Uganda invaded Kenya for its assistance to the Israelis. Fearing that a Ugandan attack on Kenya was imminent, officials at the US Department burnt the midnight oil brainstorming on how the US could come to Kenya’s rescue.

What prompted this flurry of activities in East Africa and Washington was an operation code-named Operation Thunderbolt, which was carried out by Israeli commandos to free hostages at Entebbe Airport, Uganda. The hostages had been passengers aboard an Air France Flight 139 from Tel-Aviv to Paris, France, when it was hijacked just after taking off from Athens, Greece, where it had stopped for a scheduled layover.

Among the new passengers who boarded the planes at Athens were Wilfred Bose and Brigitte Kuhlmann of the German Revolutionary Cell guerrilla group and two Palestinians from the Popular Front of the Liberation of Palestine.

As the aircraft began its onward journey towards France, the two Germans stormed the cockpit, threw out the co-pilot and commandeered the plane southwards. Their demand was the release of 53 prisoners held in five different countries.

After a brief stop in Libya, the aircraft eventually landed in Entebbe, Uganda, where the hijackers separated Jews from non-Jews. Driven by his sympathies towards Palestinian causes and the desire to project himself as an international negotiator before the world, President Amin ordered Ugandan soldiers to assist the hijackers in detaining the Jewish hostages.

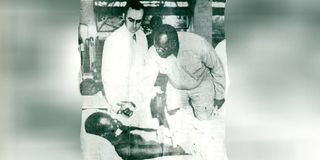

Ugandan President Idi Amin checks on one of his soldiers injured during the Israeli commando raid to free 104 hostages at Entebbe Airport in 1976.

Meanwhile, back in Israel, there was a growing sense of urgency to stage a rescue operation before it was too late. Any little information about Uganda and Amin came in handy and was quickly analysed by the intelligence and the planners of the rescue mission. Some Israelis who had trained with Amin revealed to the planners that Amin loved praise and recognition, and that a message should be sent to him that if he could successfully negotiate with the hijackers, then a Nobel Peace Prize was his to win. This was before they realised that Amin was colluding with the hijackers.

The most important information, which became central to the entire operation, was drawings from an Israeli engineer who had constructed Entebbe Airport’s new terminal in which the hostages were being kept. The Israelis then sought Kenya’s cooperation through Charles Njonjo, the then Attorney General of Kenya. Njonjo sought approval from Mzee Kenyatta, who agreed but warned that if anything went wrong, he (Njonjo) would take the blame.

Arriving in Nairobi to coordinate the Kenyan end of the operation was Lieutenant General Ehud Barak who later became Israel’s 10th prime minister. According to him the first plan was for the commando rescue team to sneak into Uganda from Kenya through Lake Victoria on speedboats. But the Mossad warned that although Kenya was prepared to cooperate tacitly, they would not agree to “such explicit participation.” In the end, the Israelis decided to conduct the operation by air.

Consequently, on July 3, 1976, four Hercules military planes carrying 200 soldiers left Tel-Aviv for Entebbe Uganda. They were accompanied by two Boeing 707 jets that were to serve as a field hospital and a command post. The planes flew extremely low to avoid radar detection, and after eight hours, landed in Entebbe in pitch darkness, catching Amin’s soldiers and the hijackers by surprise. After an intense firefight, the Israelis freed the hostages, albeit with a few casualties among them, Yoni Netanyahu the commander of the operation, and led them to the waiting planes. Within no time, the planes were already in the sky, cruising towards Kenya, where they made a stopover to refuel.

As the planes entered the Kenyan airspace, Kissinger who was following the operation keenly with regular updates from Tel-Aviv instructed the US Ambassador in Nairobi to deliver a special message of appreciation to Mzee Jomo Kenyatta and in case Kenyatta was not available, “to Koinange or possibly Njonjo, whoever has Kenyatta’s absolute confidence and was probably involved in Israel operations.” Kissinger informed Kenyatta, “I have just learned with satisfaction of the rescue of passengers on the Air France flight hijacked earlier this week. I wanted you to know that, Mr President that should Kenya require support in the days ahead, the United States stands ready to cooperate fully.”

The American Ambassador delivered this message personally to Kenyatta, who was at State House, Nakuru.. He also revealed in his report that Kenyatta, who was visibly moved, asked him to read the message twice, then told him, “I cannot find words to thank him (Secretary Kissinger).” Kenyatta then sought to know how the US could help Kenya if Idi Amin chose to retaliate. But the diplomat told him that the response would depend on the situation.

When Kenyatta pressed him further to speculate, the diplomat said that in his personal views, “US could possibly position ships off Kenya's shore which would be interpreted as support; or could speak on Kenya’s behalf with other nations.” The diplomat went on informing his seniors at the State Department, “I asked Kenyatta for his views on the present situation. Did he believe Amin might be so annoyed at Kenyan cooperation with Israel that he might attack Kenya?” And Kenyatta’s response was, “maybe, it is quite possible.”

The diplomat then sought to know whether Kenyatta or his confidants such as Njonjo or Koinange, would be keeping the US Embassy and Kissinger updated about the situation, but Kenyatta said he would handle the matter himself without involving the two. “The president said he would handle the matter and would reply if necessary to Secretary Kissinger through me himself.” Despite Kenyatta’s insistence that he would handle the matter himself, the diplomat secretly informed Washington that he thought it wise to also put Njonjo and Koinange in the picture about his discussion with Kenyatta and the contents of the special message delivered to him.

Former Ugandan president Idi Amin Dada.

As the diplomat prepared to leave, Kenyatta bade him farewell by saying, “I cannot find words to thank him (Secretary Kissinger). It is the true friends who come to our help when we are in need, that is when true friends are known.” In concluding his report to Washington, the diplomat noted, “Kenyatta appeared weak but alert during the meeting. His eyes looked somewhat glazed, perhaps from medication.

The US diplomat returned to State House, Nakuru, the following day, July 5,1976, for another meeting with Kenyatta and again on July 8, 1976. During one of the meetings, Kenyatta again expressed the fear of Amin attacking Kenya, saying, “I don’t know what this man Amin may decide to do.” He also urged the diplomat that their conversation and plans should remain a secret, adding that he would command Geoffrey Kariithi, the Permanent Secretary in the Office of the President and Jeremiah Kiereini, the Permanent Secretary in the Ministry of Defence, to maintain utmost confidentiality.

As Idi Amin heightened his war rhetoric, the Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs told his boss Kissinger, “A possibility exists that President Amin may order a retaliatory strike either ground or air against Kenya to avenge the Israeli raid on Entebbe airport and to bolster his own prestige. Following the Israeli raid on Uganda’s Entebbe airport on July 3/4, tensions between Kenya and Uganda greatly increased.”

A confidential report by the CIA around that time indicated that Idi Amin had sent a delegation to President Julius Nyerere with one special request. He wanted an assurance from Nyerere that in case he attacked Kenya, Tanzanian forces would not intervene and side with Kenya. But in his advice to Kissinger, the Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs observed, “ Reports differ as to whether the delegation was received or turned back, but it is unlikely Amin got much satisfaction from Nyerere with whom he has always been on bad terms.” In a later meeting with the US Ambassador in Dar es Salaam, Nyerere told the diplomat that nobody feared Amin and that Tanzania and Kenya were capable of dealing with him without external support.

Nevertheless, one of the main questions in the US State Department as Amin’s invasion became a possibility was “how the US should respond to any such Ugandan action.” To deter Amin, the US had already sent 2 p-3 planes, with two more on their way. Also, two warships were scheduled to call at Mombasa, while a carrier task force was already positioned between the Seychelles Islands and Diego Garcia. These were only to serve as a deterrence, but in case Idi Amin went ahead and invaded Kenya, there were other options that the US was looking at.

One was “Diplomatic Support only”. This was to involve the US supporting Kenya’s diplomatic initiatives, eg In the Security Council. But still, the Americans were to continue positioning their naval and air units in the area and also urge the UK to supply more arms to Kenya. The advantage of this option, according to the US State Department, was that it could show US support to Kenya without the US “being in front”, and that it would draw little criticism from other African countries. The disadvantages were that Kenya could regard the support as insufficient and that the UK could decline to take the lead, fearing Amin’s retribution on British nationals in Uganda.

In the second option, the US was to provide Kenya with both diplomatic and logistical support, such as supporting diplomatic initiatives, providing emergency military assistance to Kenya. The advantage of this was that it could indicate greater support and commitment to Kenya. The disadvantage was that it could trigger criticism from radical African countries and risked attracting similar support from the Soviet to Uganda, thus prolonging the conflict.

The third option was diplomatic support and direct intervention. The advantage of this was that it would be the strongest possible indication of US support to Kenya. The disadvantage was that it would evoke a negative response from other African countries, put the US in direct confrontation with the Soviet and could evoke strong criticism in the press. Fortunately, Amin never attacked Kenya.