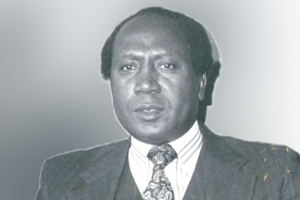

The late former cabinet minister Robert Ouko.

My name is Mervyn Maciel. I live in the United Kingdom and as I approach my 95th birthday with my memory still intact, I am writing a series of articles for The Weekly Review remembering some of the remarkable people I met during my almost 20 years in Kenya’s colonial-era civil service from 1947.

In the first instalment I wrote about my friendship with Daudi Dabasso Wabera, who I first met in 1949 when he worked as my assistant in Marsabit.

In this second article, I write about Robert Ouko and my interactions with him from the mid-1950s when we both worked in Kisii.

His assassination in February 1990 remains one of the most high-profile unresolved killings in Kenya’s history.

From 1947, when I joined the colonial-era civil service, I mostly worked in the provincial administration in various districts.

I started as a clerk and left as an executive officer in the Ministry of Agriculture. Over the years I worked in Mombasa, Voi, Kisii, Lodwar, Marsabit, Kitale and Kapenguria among others.

Also Read: How Ouko’s death shook Moi to the core

** * ** * ** *

I met Robert Ouko when he was working in the Revenue Section of the District Commissioner’s office in Kisii in the mid-1950s. The man who was born in Nyahera, Kisumu, later told me that he was previously a primary school teacher.

From our very first meeting, I got to admire this young man. He had such a friendly disposition, and I can still hear his hearty laugh almost 70 years later. He was bubbling with life and always smiling.

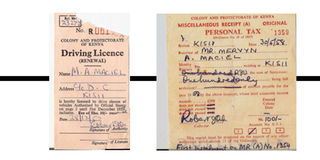

Mervyn Maciel’s documents signed by Robert Ouko, then working in the Revenue Section of the District Commissioner’s office in Kisii.

In the years I interacted with him, I never once saw Ouko angry or downhearted. I think his positive attitude was an inspiration to many of his junior colleagues as he exuded enthusiasm since joining the department in 1955.

Although Ouko and I occupied different government offices, we met quite often as I always had occasion to visit the Revenue Section. This was where I paid my personal tax and renewed my driving license. Whenever I approached Ouko, he was courtesy itself. Nothing was too much trouble for him and he was always willing to help.

For almost seven decades, I have kept some of my official documents filled in by Ouko and bearing his signature as a colonial-era government officer based in Kisii. One of the documents is my personal tax receipt of May 30, 1958 when I paid Sh100 for that year.

The other is the renewal of my driving license dated December 28, 1957 that allowed me to drive until the end of the following year at a fee of Sh10. Both were issued by Ouko — in the first instance as a tax collector and in the other as the authorising official — on behalf of the “colony and protectorate of Kenya”.

From my first conversations with him, I realised that Ouko was a very intelligent man who must have felt quite ‘humiliated” to have been given a mundane clerical job by the colonial government when he must have known that he could do much more important work.

He never complained, but in his quiet and relaxed manner decided to study in his spare time so as to prepare himself for a much better position in life.

In 1958, he enrolled with the Haile Selassie University in Addis Ababa, four years later obtaining a degree in Public Administration, Economics and Political Science. I was so thrilled when I heard of his progress and knew he would not remain long in the Civil Service doing clerical work.

Wanting to improve his prospects, he later went to Makerere College in Uganda, studying for a Diploma in International Relations and Diplomacy. This qualification must have been a great asset when he was years later made Minister for Foreign Affairs in the Daniel Moi administration, a job he conducted with great efficiency.

Ouko had obviously also by this time become a Member of Parliament. After independence he had held senior positions in President Jomo Kenyatta’s government, including serving as a Permanent Secretary.

I can still recall how, when my family and I were caught up in the Zanzibar Revolution of 1964, Ouko made enquiries on our behalf. On returning safely to my post in Kenya, I wrote a ‘thank you’ letter to him and even informed my friend and colleague at Njoro, Festus Ogada, who also knew Ouko well. We occasionally kept in touch even after I moved to the UK.

You can well imagine my shock and horror in February 1990 when I heard of his assassination in Koru. Whoever decided to kill him, did so in a most cruel and brutal manner.

I was truly stunned and saddened that such a young and promising man, with a great future ahead of him, and with a desire to do everything in his power to uplift his people, had met with such a brutal death.

This became one of the Moi regime’s worst nightmares. I have no doubt that this was a political assassination and till today I mourn a great friend and devoted son of Kenya — a politician unaffected by ambitions or greed, but a genuine desire to see the common mwananchi uplifted.