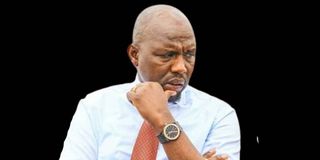

Transport Cabinet Secretary Kipchumba Murkomen.

Perhaps the anger was because of the Sh8.7 million Octo Finismo watch that the President wears, and which has become Kenya Kwanza’s symbol of opulence. Or the Sh5 million watches some of the Cabinet Secretaries now flash in public – for all to see – that angered wananchi. It could as well be the President’s Sh400,000 belt with the signature SR gold buckle. It could also be due to the “Highway” Secondary School alumni Oscar Sudi's continued donations of millions of shillings every week.

That State officials and politicos close to the President are living large is no longer news. That no one is living on a salary alone is no longer in question. When they were elected, they all claimed to be worth hundreds of millions of shillings such that we shall never question their opulence – after all, didn’t Musalia Mudavadi say he was worth Sh4 billion? Didn’t Moses Kuria tell us that he was worth Sh750 million? In total, the 24-member CSs were worth Sh15. 25 billion, according to the figures they gave when they entered office. And that is minus President Ruto's and Deputy Rigathi Gachagua’s multibillion-shilling empires.

Kenya's history of opulence is long. It started with Jomo Kenyatta, as prime minister, when he started acquiring status symbols to validate his entry into power. First, Kenyatta ordered a £7,500 Rolls-Royce car with a Coat of Arms ahead of the 1963 Uhuru celebrations. Kenyatta had ordered the vehicle after he visited a motor show in London during the October 1963 Lancaster talks. For instance, the American business community presented Kenyatta with a Lincoln Continental limousine at a ceremony conducted at the American consul general's residence in Muthaiga.

Rolls Royce

At the same period, the new Nairobi Mayor, Charles Rubia, ordered a black Vanden Plas Princess limousine – which was then a status symbol of the British Royal family. Initially, Rubia had ordered a Rolls Royce, but this caused a near-riot in City Hall as Nairobians debated why they should be subjected to such extravagance. While Rolls Royce represented the highest status symbol, the £3,400 Vanden Plas Princess was also a mark of excessive opulence.

During this period, a post-Uhuru Wabenzi culture emerged – an elite generation thrilled by luxury Mercedes Benz cars, listened to Rock n Roll, and loved Jimi Hendrix. They loved cigars and pipes, mini skirts and bohemian styles. By taking over the privileged spaces occupied by white settlers, these educated Kenyans (and some African business honchos) had membership in elite organisations, lived in exclusive estates and controlled the various pillars of the government. The Ndegwa Commission then gave them the right to do business as they wished. That is how they made their money as tenderpreneurs, or through licit and illicit trade networks where ivory, coffee and Zanzibar cloves dominated.

The death of President Kenyatta did not change the culture. Moi introduced new pests within the political State food chain and sought to undermine the Kikuyu hegemony. However, unlike Kenyatta, who had resources to give away without taking away, Moi continued to use state resources to buy power and built a multi-billion-shilling enterprise by pilfering the treasury. During Moi's time, Harambees became a platform to show-off – and fueled the sleaze market. Photos of unsophisticated civil servants such as Kuria Kanyingi donating millions of unexplained cash started to appear as the fine line between public and private was breached. Senior government officials syphoned off billions of shillings in a bogus Goldenberg diamond-and-gold-export scam.

Wealthy businessmen

It was the wealthy businessmen of the Moi era who would sustain him in power. Moi was not frugal. Though he was not as lavish as Zaire's Mobutu Sese Seko, he would also not mind gold bar donations. Once, his askaris stole his gold cockerel worth millions of shillings. Again, his love for Savile Row suits was well documented. Despite his devious character, he would still order BBC TV's Sunday religious programme, Songs of Praise, and had it flown out to him in the diplomatic bag.

During his foreign trips, Moi would take a KQ plane and pack it with busy bodies as part of the entourage. As his biographer Andrew Morton wrote, “During a visit to the Commonwealth Summit in Melbourne, Australia, in 1981, he accidentally dropped and broke the ivory rungu as he walked down the steps of his aircraft during a stopover in Los Angeles. He was so disconcerted to lose this essential prop that a replacement had to be specially flown out.” Moi would swap his Mercedes Benz for an old VW Kombi to hide his excesses as he continued accumulating wealth.

Overnight millionaires

The Moi regime created many overnight millionaires – a new class of wabenzis who were rough and unsophisticated. They grabbed public land and state properties and openly engaged in sleaze, as pointed out in the Ndungu Report. The rich and the privileged now controlled the politics and business and drove everywhere in new SUVs as their symbols of might. This class wielded influence through backroom deals and blunt coercion rather than finesse. If there was an age of wanton destruction of Kenya's economy, the Moi regime had the upper hand and had its mastes of murky dealings. Interestingly, he was not flashy and posed an ardent Christian unconcerned with wealth. That was until his estate was later laid bare.

Mwai Kibaki was mean. Age had left him sober. But in his days as Kenyatta’s Minister for Finance, he joined hands with his colleagues to establish an investment company, Heri Limited, which was quickly snapping properties in Nairobi thanks to its dealings with the government. While his presidency would be marked by economic growth, an attempt to tame the Wabenzi would flop. Once, Kibaki's Minister for Finance, Uhuru Kenyatta, tried to limit the engine capacity of the ministers' official cars. But the wabenzis were determined to frustrate the Finance minister.

If Goldenberg defined Moi's presidency, the Armenian brothers Artur Margaryan and Artur Sargsyan debacle in which privileged members within the Kibaki circle were involved in sleaze defined Kibaki's presidency. The rich flashed their flashy jewellery as an indication of wealth or status. So connected were these Armenians that a report of the Commission of Inquiry was never made public leaving Kenyan guessing on the infiltration of the security system. That those close to Kibaki could get away with such criminal activities illustrated how power was exercised by a coterie of privileged souls and their unshakeable impunity. Some of the most powerful of the Kibaki men openly flashed their new wealth. As prime participants in the money-minting Anglo-Leasing scandals inherited from Moi, they didn't seem to care.

The Uhuru presidency had its share of drama as the multi-billion projects created a new cycle of elites. The gravity of the thefts and corruption witnessed during Uhuru's presidency has yet to be fully tabulated. What is clear is that some of the money borrowed for infrastructure projects was swindled. Uhuru Kenyatta and his deputy, William Ruto, never explained their fallout, leaving Kenyans guessing it was out of the infrastructure deals. For a period of ten years, Kenya was tragically transformed and now we have a country teetering on the edge of economic collapse.

The Ruto regime is not helping either, as top leaders display status symbols while Kenyans struggle to put meals on the table. When Gen Zs say they are angry, it is all about these excesses that illustrate how we use taxpayers’ money. Again, we don’t seem to punish the Wabenzi. Instead, we have created institutions whose prime purpose is to protect their impunity as they stage crocodile tears and masquerade as poor and as people in touch with commoners. The Gen Zs have spotted the lie. The mischief.