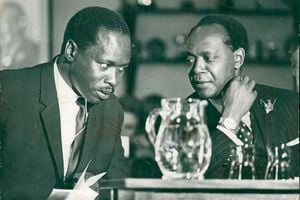

Former Attorney-General Charles Njonjo and Deputy President Rigathi Gachagua.

In the turbulent months between April and June of 1983, Kenya was engulfed in a fervent debate that revolved around one towering figure — Charles Mugane Njonjo, the man now branded as a “traitor”. His dramatic fall from grace finds uncanny echoes in the current political disarray surrounding Deputy President Rigathi Gachagua, a man whose isolation mirrors Njonjo’s lonely descent from power.

Last week, as Gachagua awaited his parliamentary reckoning, he appeared dishevelled — haunted, as though burdened by the weight of his political fate. The once-brash confidence, the aggressive bluster with which he lambasted rivals, had vanished. Now, those he had campaigned alongside were preparing to orchestrate his political crucifixion. Much like Njonjo before him, Gachagua found himself a pariah in the very arena he once dominated, his towering figure reduced to an object of ridicule. In Parliament, Gachagua had become a vulnerable target, much as Njonjo had been when Elijah Mwangale audaciously declared him the “traitor” destined for a higher office.

The similarities between these two men are striking: Both cut arrogant, imperious figures, each with a veneer of self-assured superiority. Yet, beneath their pomp, when struck by the winds of political change, they deflate like pricked balloons. While Gachagua enjoys a last gasp of backing in Mt Kenya, Njonjo could not boast such grassroots strength. His power derived not from popular support, but from his iron grip over the judiciary and security apparatus. And like Gachagua, Njonjo was known to wield a knife when necessary, betraying allies to safeguard his own ascent.

Gachagua was virile when he attacked former President Uhuru Kenyatta – even when unprovoked. On the day he and President Ruto took power, it was Gachagua who decided to humiliate Uhuru before dignitaries. More so, he continued with his attacks long after he was in power.

Mwai Kibaki, Central Kenya’s most senior politician when Njonjo was being haunted out of power, delivered a fateful blow to Njonjo when he declared that the “traitor would be shown no mercy”. It was more than an opportunistic strike; it was a calculated move to bury Njonjo politically, leaving Kibaki as the region’s dominant figure. Yet, Kibaki’s stance was not without complexity. Like Moi before him during Kenyatta’s reign, Kibaki wrestled with defending his own constituency, a task that often earned him the disdainful label “General Kiguoya” — the “Coward General”, bestowed by his fierce rival Kenneth Matiba. In the cutthroat world of Kenyan politics, survival demanded tactical retreat as much as bold action.

For Gachagua, the next chapter remains unwritten. Will he, like Matiba in 1992, play the victim card to rally support? Or will he find himself contained, as Ruto manoeuvres with the precision Moi once used to isolate Njonjo? As Gachagua prepares to face the Senate, Njonjo’s ordeal stands as a chilling precedent. Njonjo’s refusal to relinquish his power had become a national sticking point, with Bungoma South MP Lawrence Sifuna capturing the national sentiment with his biting query: “Why are we afraid of Njonjo? Is Njonjo God?”

One question pundits are asking is what President Ruto is up to. It is known that Moi’s handling of the “traitor” saga was far from haphazard. His goal was precise: Dismantle the entrenched power base within the Mount Kenya region, leaving only a handful of figures with any real influence. Aligning himself with Kibaki, Moi deliberately distanced himself from the Kiambu elite led by the likes of Dr Njoroge Mungai, Mbiyu Koinange, and Njenga Karume. Having weakened their grip early in his presidency, Moi’s final betrayal of Njonjo came as no surprise, despite Njonjo’s pivotal role in his rise to power.

Ultimate humiliation

Njonjo’s undoing was swift and merciless. While abroad, Moi had hinted at a harambee in Kisii that foreign forces were grooming a puppet for the presidency. This veiled accusation hung over Njonjo like a dark cloud. Unlike Gachagua, whose ambitions are confined to being Mount Kenya Kingpin and mediating between President Ruto and Central Kenya, Njonjo’s sights were set on the world stage, his elitist persona drawing admiration and disdain in equal measure.

Moi, and the longevity in politics helped, deftly wielded the failed 1982 coup as a tool to dismantle the remaining fragments of Kenyatta's inner circle. As rumours of Njonjo's presidential ambitions simmered beneath the surface, Moi, ever vigilant, had no intention of surrendering his hard-won power. Whether by Njonjo’s own hubris or Moi’s calculated machinations, Njonjo’s fall was inevitable. As historian Charles Hornsby noted, “Whether Njonjo truly coveted Moi’s seat or Moi simply tired of being manipulated may never be known. But Njonjo’s exit was a foregone conclusion.” The same can be said of Gachagua.

Njonjo, once so close to Moi that he would deliver him Savile Row suits from London, experienced a chilling rejection. His requests for an audience with Moi went unheeded. Gachagua, too, claims he has been shut out, his attempts to contact President Ruto blocked by lower-level officials. His ultimate humiliation arrived when he was reportedly locked out of a WhatsApp group containing the president’s schedule.

Njonjo’s remaining allies, sensing the storm brewing, scrambled for safety. Among the casualties was Deputy Speaker Moses arap Keino, who was compelled to resign after denying Parliament a chance to debate Njonjo’s crisis. The clamour for Njonjo’s resignation reached a fever pitch, with MPs demanding his removal. Yet, in a testament to either loyalty or defiance, a few — most notably Robert Matano and GG Kariuki — stood by Njonjo, even as the weight of accusations mounted against him. His Central Kenya MPs brutally left him to sink, the same way they did to Kenneth Matiba, later on.

The climax of the traitor saga unfolded on 29 June when Martin Shikuku dramatically laid before Parliament damning evidence of foreign payments made into Njonjo’s accounts. Allegations flew fast and furious — business interests in apartheid South Africa, arms smuggling, and bribery of MPs. The “Duke of Kabeteshire” was now on trial in the court of public opinion. But where Njonjo once commanded the nation’s legal and security machinery, Gachagua’s power pales in comparison. Njonjo faced allegations of being involved in coups and grand political schemes, while Gachagua's name is tied to the Gen Z uprisings — a movement branded by the government as an attempt to destabilize the nation.

On July 22, Moi dissolved Parliament in anticipation of the September 1983 election, a purge designed to cleanse the political landscape of Njonjo’s loyalists. It was not merely an election — it was the next phase in Moi’s consolidation of power, a step toward securing his dominance and ensuring his grip over Kenya’s future. Njonjo’s dramatic fall offers a cautionary tale for Gachagua. Both men, proud and unyielding, found themselves isolated, the victims of their own hubris and overreach. Whether Gachagua will follow Njonjo’s path or carve out his own destiny remains to be seen.

In their ascent to power, both Charles Mugane Njonjo and Rigathi Gachagua, much like Icarus of ancient lore, flew too close to the sun, their hubris fueling their downfall. Njonjo, once the untouchable “Duke of Kabeteshire”, wielded influence with the calculated precision of a chess master.

Yet, as his ambitions soared beyond the bounds of caution, his wings — crafted from the wax of political alliances and patronage — began to melt under the unforgiving heat of Moi’s scrutiny. Similarly, Gachagua, riding high on the waves of regional support, has found himself ensnared by the same perilous trajectory. His meteoric rise, once fueled by bravado and defiance, now threatens to end in the same flames that consumed Njonjo.

@Johnkamau1