Weekly Review

Premium

How multibillion edible oils plan became the elites’ new gold mine

Commodity imports and trading are clearly emerging as the new frontier for the rent-seeking elite in Kenya, The Weekly Review has established.

Trends suggest that the UAE capital of Dubai is the node and core of the activities of the elite.

Consider the following recent case: An analysis of Kenya Revenue Authority import entries – which are accountable documents – of three large consignments of cooking oil that were brought into the country by a Dubai-based entity under the government’s duty-free import programme, not only uncovered red flags of rent-seeking behaviour but revealed how big bucks are being made by these well-connected traders.

Rent-seeking is an economic concept that occurs when privileged groups and the well-connected seek to gain wealth without no reciprocal productivity in the economy.

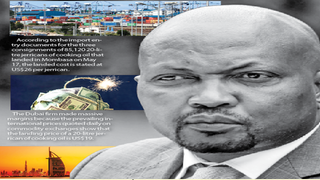

According to the import entry documents for the three consignments of 85,120 20-litre jerricans of cooking oil that landed in Mombasa on May 17, the landed cost is stated at US$26 per jerrican.

The Dubai company made massive margins because the prevailing international prices quoted daily on commodity exchanges such as the Kuala Lumpur Commodity Exchange show that the landing price of a 20-litre jerrican of cooking oil is US$19.

Clearly, the nouveau rich of the duty-free cooking oil imports game are making tidy margins. Even more revealing in the import entry documents is the fact that the origin of the cooking oil is stated as Malaysia while the exporter and the invoices are from a Dubai-based entity by the name Multi Commerce FZC whose address is stated as Sharjah, UAE.

The Kenya National Trading Company (KNTC) is named in the documents as the final consignee of the cooking oil. Thus, the big bucks were made in Dubai by the exporter of these three large consignments of cooking oil, which were subsequently sold to the KNTC.

If you do the math, the Dubai-based entity made a cool US$595,840 in profit from the three consignments.

Direct imports

Billions are at stake because the government has tasked KNTC to import 125,000 tonnes of cooking oil, ostensibly to reduce domestic consumer prices by 30 per cent, which begs the question: Why can’t KNTC import the cooking oil directly from Malaysia? Why go through Dubai and allow middlemen to reap rent?

The reality at any supermarket shelf where the product is sold under the brand name ‘OKI’ is that cooking oil prices have not come down by 30 per cent as had been promised by the government while announcing the cooking oil duty-free import programme.

The Weekly Review has learnt that the Kenya Association of Manufacturers (KAM) last month fired a letter to the acting KRA Commissioner-General, Rispah Simiyu, making the point that the duty-free import programme had not brought down consumer prices by 30 per cent.

“The way the process of imports is done will have huge negative implications on both industry sustainability and loss of revenue to KRA,” said the association in a letter signed by its CEO, Anthony Mwangi, dated May 24.

KAM made the following demands in that letter: First, that KRA provides data and details on the amount of finished edible oil imported through KNTC since January 2023; secondly, clarification of applicable import duties, levies and charges, if any, that have been paid by KNTC for the imported finished cooking oil; thirdly, full names of the exporters who have shipped these consignments; and finally, confirmation as to whether the cooking oil being imported meet all standards and complies with all laws of the East African Community.

KAM chairman Rajan Shah said the cheap imports have cut their production capacity by at least 20 per cent, adding that this has reduced the corporate tax that the government collects from processors.

The State missed out on the 10 per cent duty that’s normally collected by the Kenya Revenue Authority.

“By cutting production by at least 20 per cent, it means that companies that manufacture packaging containers have also been affected. About Sh29 billion will be lost in Import duty, VAT, IDF, and other fees, which have been waived on the importation of the 125,000 tonnes. The government will also lose corporation tax of about Sh500 million,” said Mr Shah.

Kenya Association of Manufacturers Chairman Rajan Shah. Mr Shah said the cheap imports have cut their production capacity by at least 20 per cent, adding that this has reduced the corporate tax that the government collects from processors.

Processors normally refine 600,000 tonnes of oil annually to meet the country’s total requirement. From the outset, critics questioned the wisdom of giving KNTC the responsibility of executing the big task of importing billions worth of consumer goods.

Defended programme

KNTC Managing Director Pamela Mutua, however, defended the programme, saying shelf prices had reduced “by almost half” since they started importing edible oil. “The prices will reduce further as our products hit the market, lowering the cost of living as was intended. Due to KNTC’s initiative, manufacturers have also started self-regulating and the market is now fairer to consumers,” she told The Weekly Review.

She also refuted KAM's claims that middlemen were making a killing from the scheme.

“It is common trade practice for companies in both public and private sector to use exporters familiar with the sector and countries of import to bring in commodities. This enables companies to get goods faster and cheaper. No middlemen are used in trade. The fact that KNTC products have managed to lower the cost of edible oil by almost 50 per cent despite KNTC being in the business for a few months demonstrates how some industry players have been exploiting Kenyans,” said Ms Mutua.

“KNTC has been a trading agency since 1965 and generates internal funds. Last year, we sold goods worth Sh2.6bn through our eight depots located across the country. We sold to consumers, the military, police, relief agencies and other organisations that buy in bulk. We are a profitable organisation and we rely on cash generated from our trading operations and have access to credit lines from banks that we tap into,” she added.

KNTC was until recently perceived as a moribund state-owned trading enterprise that only had relevance in the ’70s and ’80s when Kenya was still under the ancient regime of the command economy, price controls and foreign exchange allocation committees.

The fact that the KNTC supply contracts were not being given openly through transparent tendering also became a big issue. Then there was the fact that hardly months after the programme was unveiled before the project took off, there were sensational stories in the marketplace about how well-connected briefcase traders had been wandering the streets of Dubai hawking contracts from KNTC and looking for suppliers.

Pamela Mutua, the Managing Director of the Kenya National Trading Corporation. Ms Mutua has defended the programme, saying shelf prices had reduced “by almost half” since they started importing edible oil.

As criticism against the arrangement mounted, the Minister for Trade, Investment and Industry, Moses Kuria, unleashed acrimonious attacks on KAM for opposing duty-free imports of cooking oil. Appearing on a local prime-time television show, Mr Kuria spoke of the existence of a five-member cartel that was dictating high consumer prices for cooking oil. He warned the quintet of a looming “waterloo”. Mr Kuria charged that local cooking oil manufacturers did not do any significant value-addition. All they did, he said, was merely bring in imported finished products in drums to pack locally.

The minister said local firms did not deserve to be called manufacturers and derisively suggested the industry’s lobby, the KAM, should change its name to Kenya Importers Association.

As things stand, all indications are that the government is bent on seeing KNTC play a bigger role in its price stabilisation mandate. Last month, the President of the Cairo-based Pan-African trade finance provider, Afreximbank, Prof Benedict Okey Oramah, said in a press statement that the institution would support a plan to convert KNTC into Kenya’s export trading agency.

Prof Oramah, who was in Nairobi to sign a new US$3 billion programme with Kenya, did not elaborate on the scope and type of facilities Afreximbank was planning to provide to KNTC. Kenya has a vibrant edible oils processing industry made up of 13 players with a combined installed capacity of processing 2.1 million tonnes of crude palm oil per year.

Additional reporting by Gerald Andae