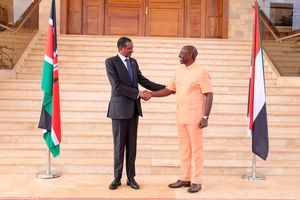

Delegates representing political parties affiliated to Sudan's Rapid Support Forces react to greetings at KICC, Nairobi on February 18, 2025, ahead of the planned signing of the Government of Peace and Unity Charter.

Sudan’s Rapid Support Forces (RSF) and its allies last month met in Nairobi to sign a charter that would see it establish a rival government in Sudan.

The move to host the Rapid Support Force RSF delegation, however, set tongues wagging with many observing that Kenya risked being reproached by Western powers especially President Donald Trump’s administration for interfering in the affairs of another sovereign country and entertaining a group whose leaders had been sanctioned by US Department of Treasury. A number of Western, Arab and African countries also criticised the move and urged Kenya to respect Sudan’s sovereignty.

However, for those who understand the underhand dealings of world powers in the pursuit of their geopolitical and trade goals, the move was not surprising. Apart from the fact that only US citizens and people under US jurisdiction are restricted from dealing with sanctioned individuals, the possibility of the involvement of Western governments and their partners in propping up the RSF cannot be ruled out. In arguing that the RSF is indirectly being supported by Western powers and their allies, Areej Elhag, a researcher at Washington Institute, observes that despite the significant atrocities committed by the RSF, America only imposed mild sanctions.

Perhaps what escaped many was that after days of uncertainty on whether or not the ceremony in Nairobi would go on, the signing eventually took place just after President William Ruto had a phone discussion with US Secretary of State Marco Rubio on February 22, 2025.

“I had a telephone conversation with the United States Secretary of State Marco Rubio. We discussed the situation in Eastern DRC, the Republic of Sudan and Kenya’s crucial role in providing a platform for key stakeholders to engage in a process aimed at stopping the tragic slide of Sudan into anarchy,” Ruto revealed on his verified Facebook page.

On the same day the president had a phone call with Rubio, there was another striking development. The United Arabs Emirate (UAE), which is a major supporter of the RSF, announced that it would be loaning Kenya $1.5 billion to plug Kenya’s budget deficit. Talks to secure the loan had been going on since November last year. While there is no proof to link the two developments to the RSF charter signing ceremony in Nairobi, their timing and the ties between RSF and UAE makes coincidence a remote possibility.

Cold War period

Since the Cold War period, Sudan has always been a strategic theatre for geopolitical rivalry by international political actors. It has vast minerals and oil reserves, it is one of the world’s leading producers of gum Arabic and Africa’s third largest producer of gold. Furthermore, it is strategically located between Sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East, bordering seven countries, and on the Red Sea, which is a vital maritime route accounting for 10 per cent of world trade. If it was to descend into total security and political abyss, the effects would be felt far and wide.

Sudan's paramilitary Rapid Support Forces commander, General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (Hemedti).

In fact, according to some of the declassified records of the US State Department, one of the reasons the US influenced John Garang of South Sudan to begin talks with the government of Sadiq al-Mahdi in Khartoum in 1986, was to curtail the influence of Muammar Gaddafi of Libya and the Soviets who were his major supporter.

“How can we exploit Moscow’s demonstrated vulnerabilities in the Mediterranean region to prevent a consolidation of a more docile Soviet-client government in Tripoli?” the Director of Policy plan asked in a document to the US Secretary of State on April 24, 1986. One of the answers to this question was to stabilise Sudan by influencing John Garang, the South Sudanese rebel leader, to reconcile with the Arab government in the North.

The Soviet-backed Gaddafi was considered anti-west, a sponsor of terrorism and religious extremism. It was feared that his continued influence in the Sudan, where he had a firm foothold, presented a huge threat to Western interests in the entire region. It was just after a terror attack on US soldiers in a discotheque in Berlin, Germany, which US President Ronald Reagan blamed on Gaddafi.

In retaliation, on April 15, 1986, US military planes launched airstrikes against Libya, killing one of Gaddafi’s daughters. In the aftermath of the attack the Director of Policy plan wrote to the US Secretary of State on April 24, 1986, “The Administration action against Gaddafi has given us renewed credibility to our willingness to use military force in support of western interests.”

The document continued, “We should use this opportunity to try to end Libyan influence and bring the northern and southern parts of the Sudan closer together. It is worth considering in this context a new direct US approach to John Garang.”

In this regard US sent emissaries to warn Garang about the danger Gaddafi posed to his Sudan People’s Liberation Army/Movement (SPLA/M) and the entire Sudan, and urged him to reconcile with the two main parties and the government in Khartoum.

It was hoped that a stable Sudan would thwart Gaddafi’s sponsored terror and his ambition to set up a federation of Muslim and Arab states that jeopardised Western interests. The plan did work out. On July 31,1986, Garang met Sudan’s Prime Minister Sadiq al-Mahdi in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. And in another sign of Gaddafi’s diminishing fortunes in the Sudan, during that same period, prime minister al-Mahdi expelled many Libyans from Sudan on allegations of being Muslim extremists. His rule was described as a freewheeling democracy, with freedom of speech, press, and expression guaranteed. He also got rid of the highly resented Sharia laws also known as the ‘September Laws’ which his predecessor Gaafar Nimeiry had imposed on the Sudan without considering the diversity of the Sudanese society with Christians in the South.

Successful coup

The only problem was he never lived up to the promises he had made to the citizenry. Consequently, in 1989, Omar-Al-Bashir took advantage of the growing discontent to stage a successful coup. Al-Bashir, assisted by his right-hand man Hassan al-Turabi, oversaw the return of religious fundamentalism, political repression, torture, arbitrary detentions, and institutionalisation of the Sharia law. During his rule, Islamist dissidents such as Osama bin Laden found refuge in Sudan. Militant groups such as al-Qaeda, Hezbollah, and Abu Nidal organisations also operated freely within the country. This resulted in the US listing the country as a State Sponsors of Terrorism.

Delegates representing political parties affiliated to Sudan's Rapid Support Forces react to greetings at KICC, Nairobi on February 18, 2025, ahead of the planned signing of the Government of Peace and Unity Charter.

Indeed, America attacked the al-Shifa Pharmaceutical Factory in Khartoum on August 20, 1998 using cruise missiles and claimed it was linked to the terror attacks against US embassies in Nairobi and Dar es Salaam that had been blamed on Osama bin Laden.

Throughout his presidency, al-Bashir maintained a very tight grip on Sudan until his unexpected overthrow in 2019. Without any influential figure to take charge, the highly centralised state inherited from al-Bashir disintegrated as factionalism became prominent. Lieutenant General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo ‘Hemedti’ of the RSF and General Abdel Fatah al-Buhran of the Sudanese Armed Forced (SAF), which claims to be the legitimate authority, tried to work together. But it didn’t take long before they went their separate ways, further worsening the situation.

While it is true that the current situation is a result of this internal power rivalry, the involvement of external actors with vested interests and allied to rival factions has exacerbated the situation. United Arabs Emirates in order to extend its commercial and geopolitical reach in the Red Sea has been investing heavily in Sudan where the Emiratis have acquired 400,000 hectares of land for farming and are also engaged in other businesses such as gold, which is found in the area controlled by the RSF. Through its “port diplomacy”, the UAE believes that Sudan apart from being crucial in its ambition of rivalling other world powers, is important in the facilitation of trade and the shipment of raw material from Africa. However, it also understands that a stable security situation is important in achieving its goals and has thus resorted to heavily arming and training the RSF even as it cut deals with them.

Although Russia is another key player in the current situation, it has been shifting goal posts depending on which side meets its emergent needs. Initially, through its Wagner group, it supported the RSF by supplying it with weapons and military training. In exchange, Moscow secured gold mining concessions in the Blue Nile and Darfur regions controlled by the RSF.

However, in the recent past, Moscow, driven by its desire to establish a military presence in the Red Sea, has been shifting towards SAF. In a deal that was signed in January this year, Russia will supply the SAF with military weapons in exchange for the establishment of a Russian naval base in the SAF controlled Port Sudan. The deal had first been discussed during the Bashir era but was never implemented because of his overthrow. However, the fall of Bashar Assad in Syria, where Russia maintained its only overseas naval base, forced Moscow to desperately turn to Sudan as the new Syrian regime refused to renew the lease.

Western allied actors such as the Israelis are mainly driven by their national security interests. It is feared that Sudan, being strategically located on the Red Sea, could easily degenerate into a major hub for terrorism connecting terrorist groups in Yemen, Somalia, and the Sahel region. What is even more worrying to Israel is Iran’s open support for SAF. In March 2024, The Wall Street Journal reported that Iran which has been trying to set-up its overseas military base in Sudan has been supplying the SAF with explosive drones and other weapons in the fight against the RSF. Israel fears that the alliance between the SAF and its arch enemy Iran presents a major threat to its own existence.

In fact, even before the overthrow of Omar al-Bashir, Sudan was already a major hub for channelling Iranian weapons to Hamas in Gaza, with the then US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton warning Khartoum in 2009, that the US considered the “activity exceptionally disturbing,” according to WikiLeaks. Two years later, a senior Hamas official was killed by an Israeli missile in Sudan while on a mission to collect Iranian made weapons, the BBC reported. And in 2012, Israel launched air strikes on a warehouse in Sudan, which it claimed was used to store Iranian weapons destined for Gaza.

It also feared that a government friendly Iran could make it easier for the Iranian backed Houthis in Yemen on the other side of the Red Sea to disrupt maritime traffic and attack ships. In December last year, the group launched more than ten missiles towards Israel, and in January this year, launched missile and drone attacks against US Warship USS Harry S Truman in the Red Sea. As a result, on March 4, 2025, the US officially designated the Houthi Movement as a “foreign terrorist organisation.

The perception held against the SAF as Islamist dominated force and its dalliance with Iran has presented an opportunity to Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo of the RSF to endear himself to the Western allies as a moderate. Riding on his diplomatic finesse, he has visited and sent envoys to many pro-West African leaders to court them. In 2013, Dagalo’s advisor likened their war against SAF to Israel’s war against Hamas. “What we are exposed to, Israel has suffered thousands of time from terrorists, such as Hamas,” said Youssef Ezzat. It is also worth noting that in 2015, with the support of UAE, the RSF sent its militiamen to fight Houthis in Yemen.

Although Israel has not come out openly to support any side in the conflict, some observers believe that while the country’s ministry of foreign affairs has been making diplomatic overtures to the SAF, Mossad spy agency has been secretly dealing with the RSF. When the Times of Israel asked a senior Israeli diplomatic official whether Mossad was working closely with RSF, the official refused to admit or deny and only replied, “We are talking to whomever we need to talk to.”

Despite the denial, the connection between RSF and the Mossad is not new. In 2021, the London based pan Arab news outlet, the New Arab revealed that Dagalo also known as Hemdti secretly visited UAE and held a meeting with Mossad chief Yossi Cohen. The paper citing confidential sources revealed that the meeting was also attended by high ranking Emirati officials.

The following year, Dagalo made another secret visit to Israel. RSF has also been seen using Israeli made weapons such as the LAR-160 smart artillery rocket and the IWI Galil ACE 31, but there is no evidence that they were procured from Israel. However, according to Areej Elhag a researcher at Washington Institute, the weapons are “further fuelling speculation that Israel is likewise supporting the RSF in spite of official Israeli claims of neutrality.”

Recent signing

There is no doubt that the recent signing of a charter by the RSF and its allies was secretly backed by Western countries or some of their allies such as UAE and Israel in the pursuit and the protection of their interests. The SAF is not considered a safe pair of hands largely because of influential al-Bashir era Islamists and extremist militants such as the Al-Bara Ibn Malik Brigade who still operate within its ranks, and its dalliance with Iran.

On the other hand, RSF, by presenting itself as a moderate group advocating for the creation of a secular state, has made it easier for the West and their partners to cast their lots with them. For this reason, it is secretly being propped up as a parallel government to checkmate the SAF and serve as a stopgap to prevent Sudan from falling into the hands of radical Islamists even as a long lasting solution to the crisis is sought.

The writer is a London-based Kenyan researcher and journalist