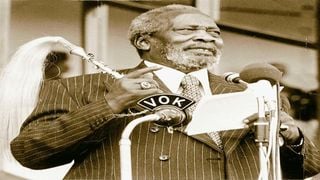

Mzee Jomo Kenyatta who in March 1963 was a minister in charge of Economic Planning.

| File | Nation Media GroupWeekly Review

Premium

Kenya at 60: From a single party to multipartysm, devolution

On August 27, 2010, Kenya promulgated a new Constitution, marking a watershed in the evolution of its democracy. Scholars, politicians and journalists have since classified developments, especially in regard to politics, power and governance, as happening before or after the advent of the Constitution of Kenya 2010.

On either side of the watershed, the frontlines of Kenya’s political arena have been dominated by political actors, especially those in power pitted against those who seek to join them or oust them, with both purporting to speak and act on behalf of those they represent or seek to represent.

The bone of contention has remained access to and distribution of resources. Also at the centre of these struggles have been civil liberties, especially the rights to free speech, assembly and exchange of ideas. Just as the colonial authorities denied Kenyans these rights, so also did independent governments brook no criticism, much less opposition.

Colonial instruments of control, such as detention without trial, found new owners in their previous critics. Before 2010, there had been momentous political developments that helped define eras in Kenya’s political history. In 1963, the centralist Kenya African National Union (Kanu) beat the federalist Kenya African Democratic Union (Kadu) to lead the country into Independence.

But the following year, the latter dissolved itself and joined the former. Kenya therefore became a de facto single party state. While a string of changes was made to the Independence Constitution arrived at in the famous Lancaster conferences of 1960, 1962 and 1963 in London, founding President Kenyatta did not legislate for a single party state, settling instead for the expansion and concentration of power in his office and person.

Kenya's first Vice President Jaramogi Oginga Odinga and the country's founding father Jomo Kenyatta. The divorce between Mr Jaramogi Oginga Odinga and Mzee Kenyatta was the moment at which Kenya lost it.

But there was no hiding the tensions at the heart of government and that the left, led by Vice-President Oginga Odinga, was becoming restless at this turn of events – the concentration of power at the centre and his own isolation from it. In March of 1966, matters came to a head, with Kanu’s Limuru Conference creating new regional party vice-presidents. Piqued, Odinga did not even consider offering himself as a candidate for the Nyanza post, which Lawrence Sagini swiftly claimed. The new offices were meant to dilute the office of party vice-president and by extension the Number Two position in government. Odinga quit Kanu, formed the socialist Kenya People’s Union (KPU) and returned plural politics to Kenya. Odinga & Co had banked on mass defections from Kanu to KPU and a showdown in Parliament.

Fearing trickle would turn to flood, Kenyatta’s corner hurriedly introduced a constitutional amendment that required defecting MPs to seek fresh mandates from the electorates. What followed was a series of by-elections that became known as the Little General Election of 1966. Kanu’s campaign theme in the by-elections, especially in Luoland, then the bastion of opposition politics, was that voting for KPU was equal to rejection of the government, which justified exclusion from government and development.

The provincial administration made it difficult for KPU to organise and in the end, Kanu carried the day. The tension between Kenyatta and Odinga, Kanu and KPU and also the Kikuyu and the Luo soon boiled over. On July 5 of 1969, Thomas Joseph Mboya, the 39-year-old Minister for Economic Planning and Development and Kanu Secretary-General, regarded by many as the enforcer of Kenyatta’s anti-KPU schemes and a future president, was shot dead in Nairobi.

Four months later, on a visit to Kisumu, Odinga and Kenyatta exchanged bitter words. When stones were hurled at the dais, Kenyatta’s security detail drew guns and threw a cordon around him. In the aftermath, KPU was proscribed and its top brass detained. Kenya was back to a de facto single party state. Kenyatta died in August of 1978 without setting foot in Nyanza again.

Contrary to fears, especially in the British press, that Kenya would slide into civil strife, the transition from Kenyatta to Daniel Toroitich arap Moi was smooth and peaceful. However, in the 90 days before a presidential poll could be held, in a sign of things to come, Mombasa politician Shariff Taib Nassir called for Moi to be elected unopposed as the second President of Kenya.

Former Mombasa Kanu supremo Shariff Nassir.

The chorus of support for Nassir’s call and Moi was overwhelming. The group that had in 1976 mooted the change-the-Constitution campaign to bar Moi from automatically ascending to the Presidency in the event of Kenyatta’s death kept its own counsel. It was silenced by Attorney-General Charles Njonjo’s claim that it was a criminal offence to imagine Kenyatta’s death.

President Moi took the reins of power with a pledge to follow in the nyayo (footsteps) of Kenyatta and made peace, love and unity (also known as the nyayo philosophy) his clarion call. In 1979, Moi named Odinga chairman of the Cotton Lint and Seed Marketing Board in a move aimed at bringing him in from the cold and as a gesture to the Luo to join the political mainstream.

But Odinga soon put his foot in his mouth. He told a public meeting that he had fallen out with Kenyatta because he was a land grabber. Moi sacked him. In the 1979 General Election, former KPU members were denied clearance to run for election on Kanu tickets.

The party high command argued that they had not had a sufficient change of heart to earn party tickets. Growing discontent was given voice by pamphlets and leaflets such as Pambana, which styled itself as the Organ of the December 12 Movement, and which were circulated clandestinely on university campuses. George Anyona and Odinga unsuccessfully tried to register the Kenya Socialist Alliance party. In June of 1982, Parliament turned Kenya into a single party state by law in a debate that took under an hour.

The failed coup of August of the same year, a naked challenge to Moi’s power, changed the man and his politics forever. Moi called the 1983 snap General Election hot on the heels of his claim that some foreign powers were grooming a certain individual to seize power.

The election was used as a sieve to rid the system of elements believed, and tagged, to be anti-Nyayo. Moi transformed Kanu into an all-powerful machine, suspension or expulsion from which spelt reputational ruin, pariah status and exclusion from politics and decision-making for the affected individuals, their families and friends. The Kanu National Disciplinary Committee became a most powerful politburo, feared and loathed in equal measure, as the enforcer of the nyayo doctrine. The massively rigged 1988 General Election resulted in the most weak-kneed Parliament Kenya had ever seen.

With the Sixth Parliament a veritable House of sycophants, Kanu’s legal dictatorship was complete, but with it also were sown the seeds of opposition to political monopoly and exclusion. In 1990, Kenneth Matiba, a former Cabinet minister, and Charles Rubia, a former Mayor of Nairobi, belled the cat. They called a news conference and demanded the return of multi-party politics.

Kenya’s politics would never be the same again. The duo were thrown into detention, but there was no stopping the demand for, and march to, pluralism. Under pressure locally and from bilateral partners, Moi relented and at a meeting of Kanu National Delegates Conference in December of 1991 at the Moi International Sports Centre in Nairobi, announced the return of multi-party politics after a generation.

But there was a catch. Section 2a, which made Kanu the sole party in the land, was expunged, but what was essentially a single party Constitution remained intact. Pleas by Mr Paul Muite for a review of the Constitution before the 1992 General Election fell on deaf ears, and so a new struggle was born – the fight for a new Constitution in synch with the era of plural politics.

It took 18 years for this dream to be realised and this side of the watershed has seen Kenyans enjoy a Bill of Rights and devolved governance, which are enshrined in the Constitution. Kenya’s Constitution is progressive because, per former Chief Justice Willy Mutunga, every chapter of it tells a story that Kenyans do not want repeated, be it in regard to human rights, sovereignty of the people, the Judiciary, the new institutions, security, public debt or finance.

The Constitution, he said in a previous interview with The Weekly Review, tells Kenyans about what must not be done again.

As politicians and lawyers are wont to say, no Constitution is perfect, but changing the supreme law is even more difficult because, as in other cases regarding public participation, the people of Kenya must sanction the change. Protecting the Constitution, the bulwark of their rights and guard rail against tyranny, is a cherished madaraka (responsibility) of Kenyans.