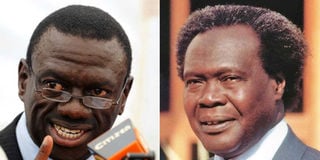

Ugandan opposition politician Dr Kizza Besigye and former President Milton Obote.

The recent abduction of Ugandan opposition politician Dr Kizza Besigye in Nairobi has revived memories of the love-hate relationship between Kenya and high-profile individuals seeking protection, including exiled dissidents, from the neighbouring country.

Archival material shows that for a long time after independence, Kenya assumed a non-alignment and non-interference stance, largely restraining itself from the internal affairs of other countries unless its domestic interests and security were threatened.

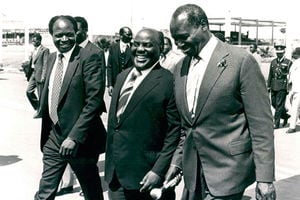

The downside of this was that Nairobi was always quick to recognise leaders who ascended to power through illegitimate means, including Ugandan dictator Idi Amin who came to power in January 1971 after leading a coup against President Apollo Milton Obote, even as other countries assumed a wait-and-see approach. In subsequent years, Nairobi continued to treat Amin with kids gloves even as other countries cut ties when he started butchering his own people.

Also, for the sake of good diplomatic relations, on a number of occasions, the Kenyan government abandoned its obligations under the Refugee Convention by mistreating or deporting Ugandan political exiles who were not in the good books of their home governments.

When Obote, who was away in Singapore for the Commonwealth Heads of State Summit was overthrown by Idi Amin in 1971, he flew to New Delhi, India, where he met Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere before proceeding to Nairobi.

But the moment Obote and his delegation landed at Nairobi’s Embakasi Airport, it became obvious to them that their presence in Kenya was not needed. Mzee Jomo Kenyatta, whose government had quickly recognised Idi Amin as the new president, snubbed the ousted Head of State as most senior Kenyan officials stayed away.

In a previous interview, Vincent Obodo, who was Obote's chief bodyguard, said his boss felt insecure in Kenya after Mzee Kenyatta completely avoided him. To give Amin more time to consolidate his coup, the Kenyan president restricted Obote's movement and communication at the Panafric Hotel, where he was staying. Assistant Commissioner of Police James Myles Oswald was entrusted with this task.

This was after it emerged that Obote, from his Panafric Hotel hideout, had contacted his loyalists in Uganda to plan a counteroffensive against Amin.

"The next day an official from the president's office of Kenya came to our hotel and told us we could not stay in the country," recalled Obote's deputy private secretary.

Six vehicles

And as Obote himself would later narrate: "I directed my delegation to ring various members in Kampala and asked whether the coup can be altered. The result I got was that it could. We had mobilised six vehicles to drive to Tororo when all of a sudden, Kenyan authorities stopped anybody from leaving my hotel. Our telephones were cut off. I decided to go to Tanzania quietly."

Meanwhile, as the former Ugandan President left for Tanzania, his wife Miria Obote, who had been stuck in Uganda after the coup, fled to Kenya with her children by hiding in a taxi and presented herself to the Kenyan immigration officials. But in a move that contravened international human rights law, President Kenyatta deported them back to Uganda after Amin telephoned him demanding their return.

Even though before deporting them Mzee Kenyatta had demanded assurances of their safety from Amin, Obote made it clear he was not happy with what Mzee Kenyatta did to his family. He believed that Kenya had put the safety of his family at great risk.

Narrating the incident during an interview Obote said: “On discovering that my family was no longer at the Kololo house (their Kampala residence), Amin contacted President Kenyatta and requested for their return to Uganda in case they were in Kenya. On finding that my family was in Nairobi and had reported their presence to the Immigration officials, President Kenyatta made Amin promise that no harm would be done to them when they return to Uganda."

But on their return, according to Obote, "Amin subjected my children, the youngest of whom was only four years old, to a TV studio interrogation asking them whether they wanted to join their father in exile."

Obote's family would later sneak to Tanzania through Kenya where they joined him in exile.

With time, Amin acquired a reputation as a ruthless dictator presiding over one of the most repressive and murderous regimes ever witnessed in Africa in the 20th Century. Kenyatta and western leaders who had supported his ascension to power were now regretting their actions as he became anti-west, anti-Israel and very antagonistic towards Kenya.

Mzee Kenyatta all of a sudden became sympathetic to Ugandans who were fleeing Amin's brutality and accommodative towards dissidents who began to strategise within Kenya on how to overthrow Amin. Making it even easier for them to operate within Kenya was the fact that most top civil servants in Mzee Kenyatta's government were Makerere graduates.

As Dr Jeromo Aliker, who was one of the Ugandan exiles operating in Nairobi recalled, "President Kenyatta was very sympathetic to Ugandans, and the Head of the Civil Service Geoffrey Kariithi was an ex-Makerere. In fact, almost all the Permanent Secretaries were ex-Makerere, and they were very sympathetic to us."

Ugandan professionals

As a result, Nairobi became the operation hub for a number of Ugandan professionals and business elite who were politically active. These exiles operated underground cells to influence political and military affairs in their country while coordinating with the armed groups that were training in Tanzania.

The rebels eventually overthrew Amin in 1979 and installed Godfrey Binaisa as interim President after Yusuf Lule’s 68-day tenure. Binaisa, a lawyer, was to serve as interim president until elections to usher in a substantive government were held in December 1980.

Among those who contested was Obote, who had just returned from exile, and Yoweri Museveni, who had joined hands with Binaisa. In the event, Obote won the election much to the dissatisfaction of Museveni and other opponents. Museveni headed to the bush to launch a guerrilla movement while Binaisa fled to Kenya together with his family.

President Daniel arap Moi, who had succeeded Mzee Kenyatta in August 1978, was suspicious of Obote, partly because he believed the newly elected Ugandan leader was working with Mwalimu Julius Nyerere of Tanzania to isolate Kenya.

However, President Moi still tried to maintain good public relations with Obote, especially because he didn't see any other person who could stabilise Uganda in case Obote was overthrown.

The Kenyan president also believed that the rebels fighting Obote, such as Museveni, were being supported by Libyan President Muammar Gaddafi who was known to destabilise other governments. He feared this could extend to Kenya in case the Libyan-backed rebels took over power in Uganda. President Moi saw Obote as the lesser evil.

Meanwhile, Obote viewed Binaisa's presence in Nairobi as a threat to his government.

Obote, therefore, requested Moi to expel Binaisa. Moi in his efforts to maintain good relations with Uganda, agreed to do so. At first, Kenyan security officials sent Aliker to tell Binaisa to leave Kenya quietly. Aliker who operated a successful dental practice in Mansion Buildings, Wabera Street, was one of Obote's spies in Nairobi.

But Binaisa, being a highly trained lawyer, rejected Aliker's advice and insisted that he could only leave Kenya on a deportation order. Two Kenya security officials were then sent to him to tell him to leave, but he again stood his ground, demanding a deportation order.

One night in October 1981, Kenyan security officers stormed Binaisa's home in Nairobi, hounded him out of his house and bundled him unceremoniously on a flight to London. His status as a former president could not save him. The only thing he had as he arrived in wintery London were the clothes he was wearing.

Not even his wife, Marjorie, and their young son knew his whereabouts. For a week, she shuttled to and fro seeking assistance to locate her husband. Meanwhile, her landlord in Nairobi, acting under pressure from Moi's government, had threatened to throw her out with her son.

It was yet another interesting turn in the relationship between Kenya and high-profile Ugandan exiles, whose latest chapter is the abduction of Besigye and his on-going trial in a military court.

The writer is a London-based Kenyan journalist and researcher.