Senior Private Hezekiah Ochuka, who had assumed the title of chairman of the People's Redemption Council, which planned to replace President Moi.

On August 1, it will be 42 years since Kenya witnessed an attempted military coup. For several hours, President Moi had lost the ability to govern. But besides the 1982 coup attempt that shaped President Moi’s politics, the 1965 and the 1971 coup talk also left Kenyatta scared and paranoid. These events were instrumental in shaping Kenya’s history in that they helped the incumbent purge the system.

Interestingly, Kenyatta and Moi knew about the plot in advance in both cases. It is how they dealt with the situation that is different and of interest to political scientists and historians. But the end result was the same: They marked the beginning of brutality.

What we know from official records is that in April 1965, Kenyatta, his Agriculture minister Bruce McKenzie and Attorney-General Charles Njonjo had received evidence that vice-president Oginga Odinga and his allies were planning some military action. But whether this was true or part of the British propaganda efforts to create a wedge between Odinga and Kenyatta is little known.

But we know from British archives that London had, indeed, set up a propaganda machine through the Foreign Office’s Information Research Department (IRD). In addition, IRD had a dirty tricks unit known as Special Editorial Unit (SEU), and Odinga was one of the targets because of his anti-Capitalist politics.

Whether the 1965 coup plot was part of the IRD imaginations is not clear – though it had profound effect on the Kenyan politics. Once he was briefed, Kenyatta started to prepare itself for an Odinga coup, which was expected to happen by mid-April 1965.

British cabinet papers

The surveillance on the VP increased. The British cabinet papers provide evidence of how preparations were made to secure the Kenyatta government. One of the known requests was made on April 4, 1965, through the then-High Commissioner Malcolm Macdonald – the previous Kenya governor – who received the request to have a warship near the port of Mombasa and troops in the country. The fear then was that Paul Ngei, who had emerged as a renegade, might team up with Jaramogi – and perhaps use the Kamba community strength in the military as his contribution to the coup.

In one of the British Cabinet records, it was confirmed that “Ministers have now agreed that Kenyatta may now be informed that in principle we would be ready to respond to a request for troops.” On offer according to records were two infantry battalions.

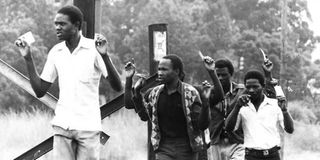

City residents flash their IDs in Nairobi after loyal soldiers regained control.

Britain also offered to send an SAS team to defend Kenyatta – and forestall any bid to assassinate him. Interestingly, Njonjo was given that information on April 14, 1965, and not the minister in charge. It seems the British did not trust other people.

Without much evidence, there was also the bid to set Odinga and create proof of a coup plot. According to Odinga, Kenyatta knew about the arms that had been stored in Odinga’s office.

According to Odinga, this is what happened: Several British newspapers carried reports in November 1964 that I had smuggled communist arms into the country, had used my office as Minister of Home Affairs to arrange their secret transport to my Ministry, and had stored the arms in the basement of the building,” Odinga lamented.

As he would admit: “I knew, Jomo Kenyatta knew, and Joe Murumbi, the then Minister for External Affairs, knew, how those arms had come to be stored in the basement of my Ministry building; that we had ordered them before Britain handed over control of the police force to Kenya’s independent Government and when the Prime Minister wanted to be able, if necessary, to equip the police independently of Britain; that the arms had arrived at Nairobi airport as a shipment consigned to the Prime Minister Jomo Kenyatta; and that it was by arrangement among the three of us that I had used the vans of the Prisons Department, which fell under my Ministry, to have the consignment conveyed for storage in the building basement. (Part of the consignment was in the safekeeping of Kenyatta himself)

Statement of protection

But no explanation was forthcoming from the Prime Minister, no statement of protection of one of its Ministers issued from the Government, and the country was left with the impression that there might possibly be some truth in these reports about my plotting. Worse than this, the removal of the arms from the basement, organized by the Ministry of Defence, was leaked to the press and reporters gathered in the early hours of the morning – while I, away from Nairobi, was not even informed of the proposed removal.”

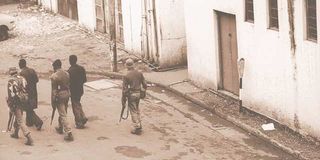

Security forces patrol the streets of Nairobi after the coup attempt.

The events that followed saw Odinga quit as vice president after he found that Kenyatta was not allocating him any duties. Odinga then left the ruling party Kanu to form the Kenya People’s Union following the choreographed Limuru conference designed to water down his might in the party. Thus, the coup talk led to significant shifts in the relations between Kenyatta and Odinga.

In 1971, there was another widespread talk of a coup. According to Moi’s biographer, Andrew Morton, the coup was discovered by chance and was backed by Soviet money and elements of the banned KPU. “Just days before the planned rebellion a Kamba army officer who was on detachment in London, having become rather drunk in a bar, revealed the plot to his colleagues.

British security services were informed, who in turn quickly informed their Kenyan counterparts and so alerted them to the danger,” he wrote. The talk, then, was that the Kenya Army boss, Major General Ndolo, was working with Chief Justice Kitili Mwendwa. While both were retired by President Kenyatta, the Yatta member of Parliament Gideon Mutiso was jailed after being implicated in the coup.

As Charles Hornsby, a historian, found out, “Ndolo’s opinions had come to the attention of the British, who discussed the mechanics of a possible attempt in detail…The British took Ndolo seriously, believing that there was ‘a real possibility of an attempt at an Army coup within the next eighteen months or so’. They concluded that it would not significantly harm British interests, but that Britain would be better served by the survival of the existing regime.”

For the second time, they had worked to protect Kenyatta. Why Kenyatta spared both Mwendwa and Maj Gen Ndolo was never known, but as former District Commissioner David Musila wrote in his autobiography, these accusations created the Kamba as a “stereotype image of a coup plotter.” Musila would host President Moi on July 30 at the Central Kenya Agricultural Society of Kenya (ASK) show at the Ruring’u Stadium.

Though President Moi was to spend the night at the nearby Sagana State Lodge, he had told Musila to proceed with the arrangements for the presidential visit – “but do not tell anyone about my change of plans.”

There were rumours that the military was planning to stage a coup by then. In his autobiography, Musila says: “I worried that the intelligence information was not clear which arm of the Defence Forces was planning the coup.” As Moi inspected the Guard of Honour, Musila “visualised a masked man opening fire on the Land Rover.” Rather than go to Sagana, Musila escorted Moi to State House, Nakuru. During dinner, according to Musila, Moi “appeared agitated.”

It is now on record that Moi had been briefed about the coup. He would later use it to purge the system of Kenyatta-era security men. While the ring-leaders Hezekiah Ochuka and Pancras Oteyo Okumu, were hanged, among other mutineers, there was a purge on the security system, and the fall guy was Air Force commander Maj-Gen Peter Kariuki, who was jailed for “failing to prevent a mutiny and failing to suppress a mutiny”.

State structures

Also mentioned during the trial was Raila Odinga, now opposition leader. There were claims that he was one of the coup organisers. Though Raila was detained without trial for six months, he was released for lack of evidence and has maintained his innocence.

As Moi’s biographer Andrew Morton later wrote, Moi used the 1982 events to strengthen his hold on the state structures. The coup plot, as Morton wrote, gave Moi a “chance to break the political and administrative shackles which had limited his room for manoeuvre since he had inherited Kenyatta’s mantle.” “It was a process he began almost at once, particularly as regards internal security. The KAF was disbanded and then radically reorganised, a number of high-ranking army officers dismissed or demoted, five provincial commissioners weeded out, the Special Branch reorganised and the uniformed police revamped.”

He also reported that a senior political figure had once approached Maj-Gen J.K. Mulinge to stage a coup. “Mulinge, quite properly, reported the matter to the authorities and the politician was picked up for questioning. Njonjo stated in Parliament that if it had not been for Mulinge’s loyalty to the constitution, ‘Kenya would now be under military rule’.”

Finally, Morton also claimed that Jaramogi and his son Raila were privy to the coup. “They were so close to it that even if they didn’t touch it, they felt its warmth.” Moi dealt with the Odinga family after that by either bringing them closer or harassing them. The coup attempts always led to the reorganisation of the Kenyan state.