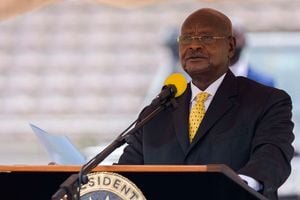

President William Ruto and his Ugandan counterpart Yoweri Museveni during a past meeting at State House, Entebbe.

When Kenya celebrated 60 years of independence in December, the notable absence of Uganda’s President Yoweri Museveni, Tanzania’s Samia Suluhu Hassan and Rwanda’s Paul Kagame spoke volumes.

That they were not invited—as the Kenyan government later explained—signified Kenya’s uneasy relations with some members of the East African Community.

Such tensions were intense in the 1970s when Kenya’s Jomo Kenyatta, Julius Nyerere of Tanzania and Uganda’s Idi Amin were at loggerheads over ideology (for Nyerere) and chest-thumping for Amin.

Of late, there has been talk of a fallout between President Museveni and President William Ruto. But President Museveni is not alone.

In July last year, opposition leader Raila Odinga claimed that State House snubbed President Suluhu after she flew to Nairobi to mediate between Azimio la Umoja One Kenya and Kenya Kwanza’s violent wrangling over the cost of living and conduct of the 2022 General Election.

Uganda has taken Kenya to the East African Court of Justice after Nairobi denied its government-owned oil marketer a licence to operate locally, and handle fuel imports headed to Kampala.

Are we back to the 1970s?

Uganda has revealed the widening fissures in the relationship between Museveni and Ruto by dragging Kenya to the East African Community court over oil transportation. Previously, a phone call between the two would have unlocked the oil transportation bureaucracy. Not anymore.

On July 24, 1976, Amin cut the electricity supply to Kenya, protesting the Kenyatta government’s alleged oil blockade, almost similar to what Museveni is going through.

Amin went on State radio and warned: “If the blockade continues, Uganda will have no alternative but to fight for her own survival.”

Kenyatta understood what that meant. War.

By then, Uganda heavily relied on the Soviet Union and the patronage of Libya’s strongman Muammar Gaddafi for its military might. Kenyatta looked up to the Americans in case Amin lived up to his threat.

Kenyatta reached out to the Americans, and Henry Kissinger flew in. The oil blockade happened as Amin continued to charge that Kenya helped Israel during the Entebbe raid of July 4, 1976, and even pointed out that Uganda once stretched up to Naivasha.

In 1987, Kenya and Uganda almost went to war after Kenya blocked oil shipments. According to the Washington Post, “Moi feels that he should be accorded respect by junior leaders in the region [but] Museveni has seemed unwilling to pay such obeisance. To Moi’s obvious irritation, the Ugandan leader has cultivated trade links with Libya and North Korea.”

President Yoweri Museveni (right) when he hosted President William Ruto at Entebbe State House, Uganda, in 2018. Kenyans and Tanzanians are these days given to asking sarcastic questions of people who come from countries that the same tough man has led for over 30 years.

Last week, as Uganda headed to the East African Court of Justice protesting Kenya’s decision to deny its state-owned oil marketer a licence to operate locally and handle fuel imports destined for Kampala, the mid-1970s row came to light.

By stopping oil flow into the land-locked neighbour via its pipeline, Kenya has rekindled memories of the Amin-Kenyatta feud when the two nations almost went to war. By then, Uganda had accused Kenya of stopping 600 oil tankers from delivering fuel.

This time, the Ruto government has used bureaucratic red tape to turn down Uganda National Oil Company’s (Unoc) application to use Kenya’s pipeline to transport its fuel.

Uganda is upset that it was kept in the dark about the negotiations around the government-to-government fuel deal between Kenya and two Gulf nations.

While Kenya argues that Unoc would displace local oil marketing companies, a profit-making avenue for political brokers, pundits say it is all about business wrangles and supremacy wars.

The political tension is more of a battle of supremacy in a region where Museveni has positioned himself as the elder statesman, being one of the world’s longest-serving presidents—he has been in power for 36 years. More so, the row with Kenya has been aggravated by Museveni’s dislike of Western powers, especially the Americans, who appear to have found a bosom buddy in Ruto, recently named by Time magazine one of the “most influential” personalities in Africa.

While the Kenyan president has become the darling of Western powers and has been receiving accolades, the same cannot be said of Museveni. As such, Museveni and Ruto no longer trust each other, and the oil wars camouflage a bigger feud.

At the moment, some of the regional disagreements are on the Democratic Republic of Congo geopolitics, which has caused Museveni and Kagame to differ. At one point in 2000, Uganda declared Rwanda a “hostile state,” and it took London’s intervention to stop the countries from going to war.

The Ugandan leader, once the darling of the West, fell out of favour with the “imperialists” (as he calls them) ever since he signed into law the world’s harshest anti-LGBTQ+ Bill—the law allows the death penalty for homosexual acts. Since then, he has been in Washington’s cross hairs. Last week, President Joe Biden removed Uganda from the list of countries that benefit from the African Growth and Opportunities Act, which allowed Uganda to import goods worth $174m to the US in 2022.

So bad is the situation that in September, when President Ruto hosted a high-level international climate change summit in Nairobi, addressed by President Biden’s envoy on climate change John Kerry, Museveni skipped the meeting. While it was claimed that he did not want to be “lectured” by Western polluters, he has openly criticised the West as “hypocrites.”

In November last year, Uganda passed a law that blocked Kenyan-based oil suppliers and gave Unoc the sole responsibility of supplying all petroleum products in Uganda. The country also stopped buying oil products from Kenyan suppliers and instead entered into a five-year contract with Vitol Bahrain EC to supply it with all its fuel needs.

Why Kenya is antagonising its biggest trading partner is not known. A few months back, Museveni accused Kenyan middlemen of inflating oil prices by up to 58 per cent; insiders attributed the rise to the convoluted government-to-government deal. Kenya abandoned the previous open tender system and instead signed an oil supply deal with Saudi Aramco, Abu Dhabi National Oil Company, and Emirates National Oil Company in March last year.

Kenya has demanded that Unoc should meet specific requirements that include proof of annual sales of 6.6 million litres and ownership of five licensed retail petrol stations and a petroleum depot. Uganda argues that these requirements are not rational and that it has the right to access the sea and transport its products through Kenya’s territory and using Kenya’s infrastructure.

It is a row that mimics that of the 1970s when Kenya demanded more cash from Uganda, which claimed to have paid for its oil delivery in full. Foreign Minister Munyua Waiyaki, was left to handle the crisis: “If the blockade that Amin is referring to is based on the fact that we have demanded cash payment, then we must tell him we are under no obligation to subsidise the Uganda economy.”

It is unclear whether Kenya still harbours the same feelings.

Kenya has always used oil as a political tool against Uganda. The suspension of petroleum shipments to Uganda in October 1978 limited Amin’s military options to fight the Tanzanian invasion in late January 1979. American oil companies—Caltex, Exxon and Mobil—stopped their supplies to the Ugandan market alleging that Amin had fallen six weeks behind in his payments.

The current oil row is a mixture of business and politics, and supremacy wars. While on the surface, it is camouflaged as a tussle over the usage of the Kenya pipeline, it points to deeper issues in regional politics.

- [email protected], @johnkamau1