Dairy firms battle it out as milk dries up

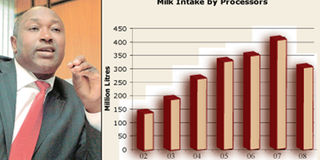

Kenya Dairy Board managing director Machira Gichohi during an interview with Sunday Nation and a graph showing the milk received by dairy firms between 2002 and 2008 (up to November 2008). Photo/ JOSEPH MATHENGE

A fierce battle for control of the increasingly lucrative dairy industry is shaping up, with the recent “merger” between Brookside Dairy and one-time bitter rival Spin Knit Dairy — a company which, however, has significantly been losing market share — being the latest manifestation.

Milk processors are engaged in vicious competition for milk, a situation that threatens to destabilise producer co-operative societies.

Most affected are Central Kenya and Eastern Province which have wrestled the mantle of top milk producer from Rift Valley. The latter was badly ravaged by the post-election crisis with many farmers and processors displaced and animals stolen or killed.

Central, Eastern and Western provinces are now producing 60 per cent of the country’s milk, with post-crisis Rift Valley – which used to contribute roughly that percentage – relegated to 40 per cent.

The economic shutdown which ravaged transport and veterinary services saw daily deliveries slide to 400,000 litres in January and stay there until March when processors received 500,000 litres.

War for control of the milk supply is partly informed by the aftermath of this political crisis. Although volumes have recovered to near last year’s deliveries, overall milk production remains below the average. Processors are using agents to lure farmers with improved prices, at times paying Sh2 on top of the prevailing range of Sh20 to Sh22.

“Long-term interests of the industry are threatened. This is a very serious issue,” said Kenya Dairy Board managing director Machira Gichohi in an interview with Sunday Nation.

While dairy farmers for now are laughing all the way to the bank, the co-operative movement, the backbone of milk production, is not.

This is for two reasons. First and most disconcerting is the fact that farmers are going off with new suitors and neglecting to pay loans advanced to them.

Second is the fact that societies are losing customers/producers and in the process economies of scale.

Here, the complaints about operations of dairy processors, particularly in producer areas of Limuru, Mukurweini and Githunguri, might not be fully justified. Producer co-operatives are at times inefficient compared to the large creameries, meaning that their operating costs form a substantial part of deductions per litre for farmers.

According to the KDB, processors argue that the industry is liberalised and as such they should be able to secure supplies, especially when they pay the right price. With daily deliveries to firms having dropped to a million litres — in contrast to a mean over 1.1 million in November and December last year — in the short run their actions are commercially justifiable.

But, if the producer societies flounder, the same farmers who are making hay when the sun shines will be back in the era of low milk prices and a processor-dictated market.

Since the government revived the industry in 2003 through New KCC, it has been on a roll. Annual intake by processors has shot up 194 per cent, from 144 million litres to record 423 million litres a year, with a huge multiplier effect on the rural and urban economies.

Dairies take just a fraction of the milk produced, which has gone up from 3.1 billion litres in 2002 to 4.2 billion last year.

For other dairies, New KCC has become major cause for worry as it moved to reclaim markets once dominated by Brookside and Spin Knit.

In part, due to this development and growing demand because of population and economic growth, processors have been forced to go to the farmer with a begging bowl where in the past they would normally dictate terms.

It could be time for the resurgent New KCC to do the worrying bit.

The firm’s intake stands at 400,000 litres daily. Brookside ranked number two swallows 350,000 with fourth-placed player — Githunguri Dairy is third at 150,000 — Spin Knit taking 130,000.

The new combination of Brookside and Spin Knit makes a total of 480,000 litres daily and could relegate the number one player to a relatively distant second. Amongst 34 active processors, other important producers include Adarsh (28,000), Meru Central (25,000), KDB-mentored Lari Dairy and Limuru Dairy (20,000).

But industry observers think the new firm, if assented to by the Treasury’s Price and Monopolies commissioner, would have the capacity to make expensive investment in powdering facilities where New KCC maintains a lucrative monopoly.

It has made hundreds of millions of shillings through sale of powdered and UHT milk to relief agencies.

Disruption of production in Kenya has resulted into discontinuation of milk exports. Kenya, thanks to colonial settlers, is the only African country outside South Africa, with a strong enough dairy sector to sell externally.

Last year it sold 22.2 million litres in the Middle East, North Africa and the region. But at present, processors have a capacity of 2.9 million daily but have to contend with processing well below this.

“There is serious competition for milk, some of it unethical,” Mr Gichohi says. He believes that processors are short-changing farmers at the current price of up to Sh22 a litre and should increase it.

Farmers have been hit hard by the maize crisis, which has doubled the price of supplements even as the price of animal drugs shoot up. KDB is doing a cost analysis for milk production to determine the right price.

Last week, a farmers lobby led by former Mukurweni MP Muhika Mutahi asked the government to intervene and avert a crisis in the industry. Mr Mutahi said the milk industry should receive the same attention maize staple has received.

It remains to be seen whether the high cost of production will halt growth in the industry. In the past six years, it has revived rural towns and animal feed plants, drugs businesses and attracted the once haughty commercial banks into the agriculture financing sector.

KDB is, however, determined to march on and put the industry on the global dairy map dominated by the likes of Australia, New Zealand, some European countries and North America.

In the meantime, they are trying to talk processors out of ruinous competition where even farmers are losing out as piqued dairies decline to pay them money owed after they defect to rivals.