Premium

Hidden sting in IMF’s billions to Kenyan coffers

An end to fuel subsidy is among the conditions that came with IMF loans to Kenya.

What you need to know:

- Heavy taxation, slash on crucial sectors’ expenditure the hallmarks of support.

- New report lays bare the pain for taxpayers in returning to global the institution for budgetary support.

Increased taxation and reduced government expenditure on critical public services such as health and education are some of the major burdens Kenyans are shouldering after the country went back to loans from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), according to a new report.

A new report released by ActionAid titled Fifty Years of Failure: The International Monetary Fund, Debt and Austerity in Africa has shed fresh light on the adverse effects that structural adjustment programmes instituted by the lender as part of its conditions for loans is having particularly on poor African countries.

Crucially, the report found that as poor countries continue to slide further into the debt trap, austerity measures are the IMF’s default solution so that its loans can be repaid, with the systemic causes of debt crises left untouched.

During his 10-year reign between 2002 and 2012, then President Mwai Kibaki had largely shunned external lenders such as the World Bank and the IMF to finance his budget, but the Bretton Woods institutions made a comeback during the Jubilee administration under President Uhuru Kenyatta.

In May 2020, the IMF loaned Kenya $739 million (Sh110 billion at current exchange rate) drawn under the Rapid Credit Facility (RFC) to address the country’s urgent balance of payment needs that stemmed from the Covid-19 pandemic.

In April 2021, Kenya inked a $2.43 billion loan programme with the IMF under the Extended Fund Facility (EFF) and Extended Credit Facility (ECF) to be disbursed over a period of 38 months. In May 2023, the programme was extended by 10 months

But these loans came with tough conditions to be fulfilled by the Kenyan government, including increasing taxation, cutting public expenditure, reforming State-owned enterprises (SOEs), cutting the budget deficit and taming inflation.

Members of the National Assembly during a sitting on June 7, 2023. Parliament has approved the conversion of Kenya’s Sh10 trillion debt ceiling with a debt anchor as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP), fulfilling a promise to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) by the previous administration.

As part of the study, ActionAid reviewed 37 IMF loan documents and Article IV Report policy advice published between July 2021 and January 2023 for 10 African countries: Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

Also Read: The waning shilling

The report found that “the IMF’s insistence that countries prioritise debt repayments, rather than seeking a systemic solution to debt, is a major obstacle to spending on health, education and climate action”.

It stated that about six billion people globally are now facing austerity measures, largely owing to the “IMF’s reluctance to accept that its economic model has failed”, it said. The IMF, for instance, re cently backed President William Ruto’s controversial Finance Act, 2023 which contained new tax measures that have further pushed up the cost of living.

Also Read: Ruto flips back to Uhuru footsteps

The Act doubled value added tax (VAT) on fuel to 16 per cent, introduced a 1.5 per cent housing levy on salaried workers and raised income tax on high income earners.

Despite fierce opposition to the Act leading to a court battle, the law is currently in place, with the lender hailing it as key to reducing Kenya’s fiscal deficit.

“The approval of the FY2023/24 Budget and 2023 Finance Act are crucial steps to support ongoing consolidation efforts to reduce debt vulnerabilities while protecting social and development expenditures,” said the IMF.

The report also found that one of the clauses in the IMF loans which forces countries to reduce inflation to within a specified range has had a devastating effect on the economy particularly because of the sharp increase in lending rates to tighten the fiscal space.

This is despite the fact that most Kenyan households and businesses rely on loans to meet their daily needs and business operations respectively.

“The IMF sees as an absolute priority and this is usually achieved by recommending increases in interest rates, to reduce the amount of money circulating in the economy. One direct consequence of this is to squeeze resources available for public spending,” says the report.

International Monetary Fund headquarters building in Washington, DC.

Kenya finds itself in a tight fiscal spot amid sluggish growth in revenue collection and rapidly rising domestic interest rates which have made it extremely expensive for the government to borrow from the local market.

This means loans from external lenders such as the IMF have become very crucial especially as a source of much-needed foreign currency as the country continues to brave a scarcity of forex.

This has led to the current situation where despite the IMF being only Kenya’s fourth largest external lender, it has the lion’s share say in the country’s policies, which is having a debilitating effect on Kenyans.

By April, Kenya owed the IMF Sh325.49 billion, which is lower than the Sh489.53 billion owed to the Asian Development Bank (ADB), China (Sh856.38 billion) and the World Bank (Sh1.443 trillion).

Kenyans will also remember the tough stance that the lender has had on subsidies on key products including fuel, electricity and food, calling for their complete withdrawal.

President Ruto has heeded this call and withdrawn all subsidies on the products, only retaining a subsidy on fertiliser.

This comes at a time the spotlight has been directed at multilateral lenders over the high interest rates compared to development countries as the former are considered a higher risk when it comes to defaulting.

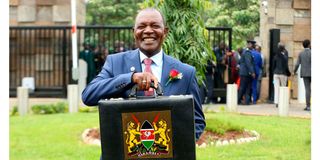

National Treasury Cabinet Secretary Njuguna Ndung’u at Parliament Buildings for the reading of the 2023/24 Budget Statement on June 15, 2023.

The UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) recently found that countries in Africa pay interest rates that are four times higher than the US and eight times higher than Germany – and that the amount African governments are forced to spend on interest payments is often higher than expenditure on either education or health.

The report further found that 80 per cent of countries were advised to cut or freeze the share of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) spent on wage bills, which is constraining public sector employment, and that all 10 countries were effectively advised to end up with a public sector wage bill that is under the global average (nine percent of GDP).

In its recommendations, the report has called for the IMF to re-think its attachment to austerity measures, and that if the lender does not, “African governments should reject the IMF’s advice and pursue a different path”.

“African governments should pursue alternative economic paths that place quality public services, social and economic justice at the heart of building sustainable and truly sovereign states,” it said.