Business

Premium

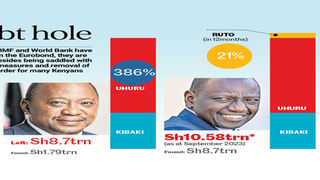

Inside Kenya's debt hole as IMF, World Bank approve additional Sh2trn loans

What you need to know:

- The IMF last week approved additional financing of Sh143.4 billion.

- Public debt could exceed Sh10.9 trillion by June 2024 even as Ruto roots for borrowing from pension savings.

Kenya is set to receive new loans totalling about Sh2.1 trillion from the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) over the next three years.

This, even as President William Ruto continues to push for borrowing from pension savings as a likely antidote to the country’s growing reliance on external loans.

The country received a major boost last week when the IMF approved additional financing of $938 million (Sh143.4 billion) through the 48-month Extended Fund Facility (EFF) and Extended Credit Facility (ECF) programme.

Following the approval, the lender is set to wire Sh104.3 billion ($682.3 million) for budgetary support to Kenya in January after it concluded the sixth review under the programme.

When the disbursement is made, it will bring the total amount of loans that Kenya has received so far from the lender since the deal was approved in April 2021 to Sh409.9 billion ($2.68 billion) .

Putting into consideration the National Treasury's borrowing target for the FY2023/24, public debt could exceed Sh10.9 trillion by June 2024.

This means that, excluding borrowings from other multilateral, bilateral and commercial lenders, the IMF and World Bank loans will increase Kenya's debt past Sh13 trillion by the end of the three-year period.

The EFF/ECF deal, in addition to the new Resilience Sustainability Facility (RSF) that was approved this year, will see the IMF lend a total of Sh677.5 billion ($4.43 billion) to Kenya over the duration of the programme.

National Treasury and Economic Planning Cabinet Secretary Njuguna Ndung’u.

“The tightening global financing conditions for frontier economies and global geopolitical tensions are compounding the challenges from the legacy of the pandemic and multi-season drought, further straining Kenya’s balance of payments and fiscal financing requirements,” said IMF’s Mission Chief to Kenya Haimanot Teferra.

In addition to the IMF financing, the World Bank last week announced that it would lend about Sh1.83 trillion ($12 billion) to Kenya over the next three years. The loans will be disbursed by the World Bank’s various arms.

“Subject to the World Bank Executive Directors approval of new operations, and to factors which may affect the Bank’s lending capacity, this implies a total financial package of $12 billion over the next three years,” said the bank in a statement.

This brings to total Sh2.1 trillion the amount of new loans that are set to be disbursed to Kenya by the IMF and the World Bank over the next three years, starting with the latest Sh104.3 billion tranche that is due from the IMF in January.

The loan has given Kenya a new lease of life even as the burden of the $2 billion (Sh305.9 billion) Eurobond that is due for payment in June next year hangs on its neck.

President Ruto recently said Kenya will next month pay the first instalment of the loan totalling $300 million (Sh45.88 billion).

The major worry that a section of the public has over the increased reliance on loans from the IMF and World Bank is the tough conditions attached to them, which are akin to the infamous structural adjustment programmes (SAPs) of the 1980s and 1990s that some observers say crippled the Kenyan economy.

The IMF has, for instance, successfully pushed the Kenyan government to abolish subsidies on fuel, electricity and food.

Coupled with high global crude oil prices and a weakening shilling, the situation has led to historic high fuel prices.

Further, the lender has backed tough taxation measures introduced by President Ruto, such as the housing levy and doubling of Value Added Tax (VAT) on fuel, which it says will help raise revenue and lower the fiscal deficit.

But according to the National Treasury, the concessional financing from the IMF and World Bank is critical for the country at a time when global and domestic interest rates remain elevated, which makes it a costly affair for the government to borrow on commercial terms.

“In light of the uncertainty surrounding access to global bond markets, the government strategy has shifted to focus on seeking out concessional funding from the multilateral lenders like IMF and World Bank and bilateral development partners,” said Treasury Cabinet Secretary Njuguna Ndung’u in a statement.

The new loans from the Bretton Woods institutions have also eased fears that the country could default on the Eurobond, but are plunging Kenya into a deeper debt hole.

This also comes at a time when Parliament has amended the debt ceiling from a nominal value of Sh10 trillion to an anchor set at 55 per cent of the GDP.

The Treasury, however, says various government interventions are set to see the fiscal deficit as a share of the GDP decline from 5.6 per cent in financial year (FY) 2022/23 to 4.7 per cent in FY2023/24 and further to below four per cent in FY2024/25.

“The government has made great strides toward the budgetary adjustments needed to alleviate debt concerns,” said Prof Ndung’u last week.

“This has been achieved by sustaining our efforts in revenue mobilisation, reducing non-core spending while giving high impact social and investment expenditures priority.”

President Ruto has also outlined his plan to use the retirement savings of Kenyans to borrow in a bid to shift away from reliance of external loans amid rising global interest rates.

During his inauguration in September last year, the President decried Kenya’s low national savings as a share of gross Domestic Product (GDP) compared to its regional peers.

“We are borrowing from other countries because they build their savings ahead of us. But now, instead of us going to borrow from other people, we have our own savings so that the government can borrow from the ordinary Kenyan,” said Dr Ruto last week.

“Our plan is to ensure that our savings as a percentage of the GDP which is now at between eight and 10 per cent, (will increase) to 20 or 25 per cent in the next 10 years,” he added.

To that end, the government in February raised mandatory monthly contributions to the National Social Security Fund (NSSF).

This came after the Court of Appeal ruled that the NSFF Act of 2013 was constitutionally enacted thereby paving the way for its implementation.

The Act revised the monthly contributions by both employees and employers from a fixed amount of Sh200 to a six per cent deduction operated in the Tier 1 and Tier II system.

As a result, NSSF now collects approximately Sh4 billion every month from its registered members, up from the Sh1.3 billion previously, giving the government a wider pool of funds to borrow from.

It remains to be seen how soon the President’s plan could bear fruit, considering the huge amounts of money that the government borrows annually. In the current financial year alone, the fiscal deficit is estimated at Sh634.1 billion.