President William Ruto signs the Finance Bill, 2023 to law at State House, Nairobi on June 26, 2023.

In his first 17-month in power, President William Ruto has borrowed comparatively higher and spent lower on development than his two predecessors, despite collecting much more in taxes, underlining the growing public debt menace.

This is based on a Nation analysis of the three presidents’ priorities on assuming office, which, however, shows President Ruto has, to his credit, spent a lower proportion on recurrent budgets- salaries and allowances- compared to his predecessors.

Granted, all the three presidents came into office facing different challenges.

In 2002, Kibaki said he was “inheriting a country, which has been badly ravaged by years of misrule and ineptitude,” and that the economy which has been “under-performing since the last decade is going to be my priority.”

Retired President Uhuru Kenyatta in 2013 acknowledged his predecessor in “the past 10 years has laid a firm foundation for the future prosperity of our country” and pledged to use “all the money that comes from natural resources for development programs.”

And in 2022, President Ruto observed “people are confronted daily with increasingly unaffordable prices, especially food and transport” and committed “an urgent and decisive resolution.”

So how did they conduct affairs within their first 17 months in office?

On the revenue side, President Ruto has borrowed 37.8 per cent of the money he raised, compared to Uhuru who borrowed 31.7 per cent of the revenues in his first 18 months, and Kibaki’s 26 per cent as a share of revenues over a similar period from January 2003.

On spending, President Ruto put just 11.7 per cent (Sh551 billion) of the Sh4.7 trillion he spent between October 2022 - February 2024 to development, against Uhuru and Kibaki’s 15.6 per cent development spending during their initial 18 months in office.

The analysis of government revenues and spending reveals that while President Ruto finds himself in a tight debt-service corner that is taking about half of all the money he is spending, he continues to borrow more and is deviating from his first commitment as President, that “when you find yourself in a hole, you stop digging further.”

Between October 2022 and February 2024, President Ruto’s total government revenues amounted to Sh4.8 trillion, out of which taxes accounted for 59.8 per cent while borrowing filled in 37.8 per cent.

Despite collecting higher taxes and borrowing more, development spending remains low.

While tax contribution to total revenues during similar periods for Kibaki and Uhuru were a similar 59 per cent, the former Heads of State borrowed less during their first 18 months in office- Uhuru (31.7 per cent of the Sh2.24 trillion revenues) and Kibaki (26 per cent of the Sh500 billion revenues).

“Now he (President Ruto) has dug that hole, (so that) even coming out of it with elevators will be a nightmare. The country is highly indebted. This means that we are living beyond our means,” says Dr Samuel Nyandemo, Economics lecturer at the University of Nairobi.

Kenya Private Sector Alliance (Kepsa) CEO Caroline Kariuki notes that increased domestic borrowing particularly “has posed a challenge of private sector credit crowding-out effect.”

“Notably half of Kenyan banks were accessing liquidity support from the Central Bank of Kenya (CBK) by the end of September 2023. This challenge in credit access inhibits private sector ability to create job opportunities due to limited funding,” Ms Kariuki says.

Between July 2023 and end of February 2024, the government borrowed Sh737 billion from domestic and external markets. It had borrowed Sh1 trillion between October 2022 and June 2023.

The high rate of borrowing under the current government has been despite its commitment- in speeches and policy documents- to take less debt and rely on taxes more to implement development priorities.

This has seen the government introduce an array of new taxes and levies, which experts and industry leaders now blame for the Kenya Revenue Authority’s missed targets.

Among taxes and levies introduced/raised since last year include the 1.5 per cent housing levy, increase in value added tax on fuel to 16 per cent and the export promotion levy.

Kepsa and the Kenya Association of Manufacturers (KAM) argue that more taxes and levies have affected several sectors in terms of productivity and job creation, and have had a counter-productive effect on targeted government revenues.

“When we see KRA missing revenues by Sh36 billion every month, there is an attribution to what is happening in the sectors that have been affected by the Finance Act, 2023,” says KAM CEO Anthony Mwangi.

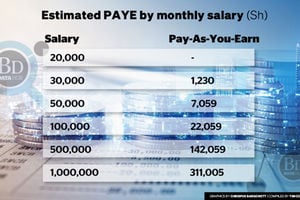

He notes that the contribution of many companies to VAT, Import Duty and PAYE has diminished due to increased taxes on businesses and workers.

KAM says uncertainty of tax policies is a major concern for manufacturers and that newly introduced levies, especially on industrial inputs is curtailing manufacturers’ productivity by making them uncompetitive in the region.

“We urge the government to consider not imposing taxes on industrial inputs since no country in the world is self-sufficient in industrial inputs. Imported industrial inputs act as building blocks for exports and imposing taxes on imported industrial inputs denies the country capacity to add value locally and benefit from technologies embedded in imported inputs. Thus, undermining economic growth prospects,” Mr Mwangi says.

Dr Nyandemo says new tax measures by the government are “disillusioning businesspersons from any serious business engagements because there is no morale and motivation.”

That has been the overall performance on raising revenues.

President Ruto has in his initial 17 months put Sh11.7 out of every Sh100 at his disposal on development against Sh15.6 that each of his two immediate predecessors put during similar periods (18 months).

President Ruto’s spending on development is, thus, about 25 per cent lower.

Government spend on development between October 2022 and February 2024 was Sh551 billion out of total spending of Sh4.7 trillion.

Between April 2013 when President Uhuru took over power and September 2014 when his first 18 months in office lapsed, he spent Sh369 billion out of Sh2.36 trillion on development.

Kibaki’s development spend was Sh66.4 billion out of Sh425 billion between January 2003 and June 2004.

National Assembly’s Budget Committee Chairman, Ndindi Nyoro, blames low development spending in President Ruto’s government on high allocations to debt service which he terms as “money that would otherwise go into development” and prioritising “what must be done fast.”

“You ask yourself, between paying a teacher/nurse and building a road, what can wait. It’s a matter of sequencing and it is basically to stabilise. When stability is achieved, now we go back to normalcy of allocating enough resources to development. There has been some tightening in terms of development financing but it’s just a matter of us seeking stability,” Mr Nyoro says.

Between October 2022 and February 2024, the government spent Sh2.3 trillion (49 per cent of total spending) on the Consolidated Fund Services (CFS), which almost entirely constitutes public debt service. Uhuru and Kibaki spent 26 per cent and 11 per cent respectively, on the item.

“When you hear the President making appeals to global financial institutions to lower rates, it’s basically because all the money we allocate to CFS is going into payment of interest rates. If they just halve the amount they are charging, we would have another leg room of more than Sh400 billion to put into development,” Mr Nyoro says.

But much of the development spending is diverted to recurrent spend through supplementary budgets within the year, as additional borrowing is factored beyond what had been approved in original budget.