Scientists find why deadly brain cancer returns

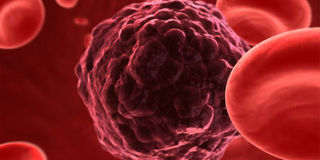

Some cancers, such as brain cancer remain on the margins of these new treatments. PHOTO| FILE.

What you need to know:

- In response to treatment, high-grade gliomas appear to remodel the surrounding brain environment; potentially creating interactions with nearby neurons and immune cells in ways that protect the tumour cells and hide them from the body's defences.

- Experts explain that glioma brain tumours are rare but a diagnosis is devastating because there is currently no cure.

Scientists working on a cure for cancer have established that the deadliest form of brain cancer returns because tumours adapt to treatment by recruiting help from nearby healthy tissue.

In a new peer-reviewed study done by a global team including University of Leeds, experts observed that in response to treatment, high-grade gliomas appear to remodel the surrounding brain environment; potentially creating interactions with nearby neurons and immune cells in ways that protect the tumour cells and hide them from the body's defences.

They further found that lower grade tumours often develop a new mutation that allows the cells to start dividing more rapidly, potentially catapulting them into a higher-grade form. Experts explain that glioma brain tumours are rare but a diagnosis is devastating because there is currently no cure.

“Low-grade gliomas have a better survival rate than high-grade gliomas, but often progress to high-grade gliomas. More than 90 per cent of patients with high-grade tumours die within five years,” they stated.

According to Dr Lucy Stead, an associate professor of brain cancer biology at University of Leads’ School of Medicine as well as the lead UK academic for the study, current treatments include surgery, radiation therapy and chemotherapy but findings indicate that new drugs are needed to supplement these.

"The brain is a hugely complex organ made up of lots of different types of cells, and brain tumours are equally diverse and complicated. Learning from patient tissue is the best way to cure the patient's disease. This study, which required a global effort to acquire enough glioma samples to adequately power it, has allowed us to gain unprecedented insight into how these deadly tumours progress, and ways that we might finally be able to stop them," the lead researcher disclosed.

The team highlighted that Sue, a brain tumour patient from York, died in September 2017 after a seven-year battle with the disease.

This is why Geoff, her husband of 50 years who is now an ambassador for Yorkshire’s Brain Tumour Charity taking part in events to help raise funds for brain cancer research and awareness, while welcoming the findings said, “Sue fought bravely and without a single word of complaint or self-pity for seven years. This is my driver. The types and positions of tumours make this a difficult one to actually solve”.

He sees it a scandal that the survival rate for brain tumours is no better now than 40 years ago. “It seems from my experience that a one size fits all approach is applied to treatment at the moment and any form of targeting treatment specifically to suit the person must be an improvement.

“The fact that research is being undertaken has also a beneficial effect on patients and their families. It generates hope.”

The researchers say they are now investigating why gliomas progress to a higher-grade form, and why they survive and continue to grow after treatment.

They collected multiple samples of gliomas over time, as they transitioned from low-to-high grade, and before and after treatment. They then looked at how the cells changed and adapted to see if they can find ways to stop them, by using novel drugs.

The mutation and previously unknown cellular interactions could now be targeted with novel drugs that stop the tumour cells from progressing and adapting to treatment. In this way, the study has opened new avenues of research that may yield more effective drugs to offer patients.