COP30 climate deal misses deadline as delegates fight over finance

Brazil's President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres and other delegates attending the Belem Climate Summit ahead of the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP30) in Belem, Brazil, November 7, 2025.

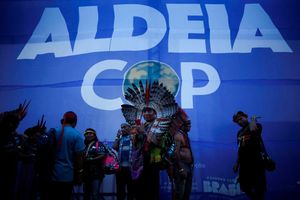

In Belém, Brazil

Negotiations at COP30 entered a tense and uncertain phase on Thursday after the Brazilian Presidency made an aggressive but unsuccessful attempt to force agreement by late Wednesday. What was meant to be the decisive turning point for the summit instead exposed the deep fractures still running through the talks and the limits of the Presidency’s ability to bend the process towards a swift political finish.

The turbulence began late Tuesday evening when the COP30 Presidency circulated a brief but pointed communication informing delegations that a streamlined “Belém political package” would be issued at dawn on Wednesday, triggering a rapid round of ministerial consultations intended to lock in a deal within hours. All remaining items, advised the note seen by the Nation, would be pushed to Friday, effectively creating a two-track endgame.

“In preparation for tomorrow, the secretariat wishes to inform Parties of the COP30 Presidency’s anticipated plan for adopting the Belém political package on Wednesday, 19 November,” started the advisory note. “On the Belém political package, texts are to be published early morning Wednesday, 19 November. Following the release of the streamlined draft texts, the Presidency plans to engage Ministers to progress toward agreement. On items not included in the Belém political package, work on these will continue tonight until midnight, with a view to preparing texts for adoption on Friday, 21 November.”

The move was widely interpreted through the prism of political choreography. President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva flew into Belém from Brasília on Tuesday and was scheduled to fly out on Wednesday night. His visit was brief enough to raise eyebrows among negotiators, many of whom suspected the presidency intended to produce a draft agreement quickly enough for Lula and UN Secretary-General António Guterres to carry a political “win” into the G20 summit in South Africa later this week.

Reacting to the developments, Mohamed Adow, director of Kenyan climate policy think tank Power Shift Africa, said “it’s good to see some proper leadership and a COP host taking their job seriously, after the slapdash efforts from the Azerbaijanis in Baku last year”.

He continued: “I hope this gives the COP some impetus to deliver a clear plan for getting climate finance to vulnerable countries, a clear mechanism for just transition and a roadmap for phasing out fossil fuels. But the danger is that the Brazilian hosts are so keen to get any kind of agreement over the line that they only suggest a weak package that doesn’t really do much to help the climate vulnerable and the planet.”

On Wednesday night, the Presidency issued another note, indicating that it was not changing tack to shuttle diplomacy to resolve the impasse.

“Upon reflection of inputs received from Parties, the COP30 Presidency will undertake shuttle diplomacy on text proposals with negotiating groups, commencing in the morning,” it said in the advisory to government representatives.

But, even as the presidency pressed for urgency, the sharper divisions within the negotiations were impossible to obscure. Central among them is the question of adaptation finance, a long-standing fault line now further strained by mounting climate impacts and the growing fiscal pressures facing developing states. The African Group of Negotiators (AGN) has repeatedly pointed to the continent’s adaptation funding gap, estimated by analysts at more than US$2.5 trillion by 2030. For the AGN, “this is the measure of whether the climate talks are meaningful to communities living on the frontline of droughts, floods and spiralling food insecurity”, said Dr Richard Muyungi, chair of the African Group.

Also read: COP30 final week: Finance crisis threatens climate action as Africa seeks wildlife commitment

Dr Muyungi’s group of African negotiators has argued throughout the summit that any final package must embed clear financial guarantees for adaptation. Their stance has support from the wider G77 and China group, which has warned against an outcome that prioritises monitoring frameworks over actual delivery. At a press briefing on Tuesday evening, Ms Lina Yassin, a Sudanese negotiator speaking for the Global South, said “there is growing concern that the heavy emphasis on ‘indicators’ under the Global Goal on Adaptation risks creating an illusion of progress without unlocking the funding needed for implementation”.

The presidency’s fast-track plan has also intensified tensions over the fossil-fuel transition, a topic that has plagued COP after COP without yielding a decisive consensus. Campaigners have pushed relentlessly for the Belém outcome to include strong language on phasing out coal, oil and gas, along with mechanisms to ensure a fair transition for workers and communities in fossil-dependent economies.

Their demands have been met with resistance from fossil fuel lobbyists, whose overwhelming presence in Belem was earlier in the week describe by UN human rights experts as worrying. Fossil-fuel-industry-affiliated participants constitute roughly one in every 25 attendees in Belém, with over 2,200 fossil-fuel representatives registered out of more than 56,000 delegates. The experts cautioned that such a presence threatens the credibility and integrity of the negotiations, arguing that the process must serve the public interest rather than entrench the influence of industries historically responsible for the climate crisis.

As Wednesday came and went without the breakthrough Belém package the presidency had hoped for, the pressure has shifted onto ministers. The technical negotiators, who have been painstakingly working through text for nearly two weeks, have been largely sidelined from the decisive political phase now unfolding. At the time of writing this report, ministers were locked in a series of closed-door sessions, bilateral meetings and regional caucuses that appeared poised to stretch late into the night.

The opacity of this stage is drawing unease from some delegations, who worry about rushed compromises being stitched together without consultation. The sentiment inside several rooms, according to diplomatic sources, is that the Presidency’s push for speed is clashing with the need for substance.

"Honest broker"

The presidency has repeatedly invoked the spirit of “Mutirão”, the Brazilian ethos of collective effort that has been a symbolic pillar of COP30. Throughout the conference, Mutirão has been used to frame an image of inclusivity, community and cooperation, an attempt to position Brazil as an honest broker capable of holding together diverse and often divided parties. But as the talks have shifted into their high-stakes endgame, that rhetoric now sits uneasily alongside the narrower, more controlled decision-making of closed-door ministerial consultations.

For many delegates, Mutirão remains more an aspiration than a reality. Several developing-country negotiators have privately voiced concern that the presidency’s pace risks squeezing them into choices without adequate review time. The fear is that a rushed political package may reflect expediency rather than consensus, particularly on issues that require careful balancing of national interests and global responsibilities.

For Brazil, the diplomatic stakes are considerable. Hosting a COP in the Amazon carries symbolic weight, and the global gaze on Belém has been intense. A strong, credible outcome would reinforce Brazil’s self-portrait as a climate leader. A watered-down deal, rushed through under time pressure, would leave the presidency vulnerable to criticism from both civil society and developing blocs that dominate the negotiations.

Follow our WhatsApp channel for breaking news updates and more stories like this.