I give my breast milk for free to save babies

The milk bank where breast milk is processed and stored at Pumwani hospital.

What you need to know:

- For a mother to donate her milk, she is screened for Hepatitis B, C, HIV/Aids and syphilis.

- So far the milk has helped 325 babies.

- A total of 577 mothers have donated their milk to it.

- According to WHO, premature babies have a higher chance of survival if fed with breast milk instead of formula.

Margret Wanjiru delivered her third baby girl on October 23, 2020 at Pumwani Maternity Hospital. Her baby was prematurely born at 36 weeks through a caesarean section.

The baby was taken to the nursery in order to mature to term and gain more weight before discharge. “I had a lot of milk and my baby took very little. My breasts were so painful in the initial days. I decided to express and donate to other babies in the hospital,” says Margret, adding that she has been expressing about 120ml twice or once a day.

“This is my first time to donate milk after being asked to volunteer by the hospital nurse.”

Initially, she would even express a lot more three times a day. Now she needs to balance between the milk she donates and that of her growing baby. “I lost my two children at three years and one year because of insufficient calcium. So, when I was asked to help, I volunteered because I wanted to save a child,” says the 24-year-old.

Unlike Margret who gave birth in hospital, 26-year-old Shantelle Mueni delivered her first child at home on October 26. But her baby boy developed breathing complications immediately after birth and was taken to hospital the same day, admitted and later taken to the nursery.

Teenage mothers

“My baby was not feeding much and my breasts were engorged all the time. I volunteered to donate my milk to others babies,” she recalls. “I express the milk twice a day and I will do it until I am discharged or if the milk flow goes down.”

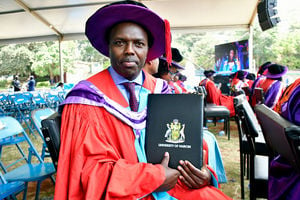

Margret Wanjiru, a donor to the milk bank at Pumwani hospital.

Margret and Shantelle are among the over 500 women who have volunteered to donate their breast milk at Pumwani hospital’s milk bank unit. The milk helps vulnerable newborns whose mothers have died, are very sick or cannot produce enough milk.

“These mothers are doing an extraordinary thing from their hearts with an intention of saving other babies. It is not easy,” says Kezia Njau, a nurse and counsellor at the hospital.

The milk bank was launched in 2019 by the Health ministry and the Program for Appropriate Technology in Health, USAid and African Population and Health Research Center with the aim of reducing newborn deaths at the hospital.

The unit cost $57,000 (Sh6.2 million) to set up.

Pumwani hospital has the largest number of deliveries in the country. Up to 70 or more deliveries are carried out daily. A majority of the mothers are teenagers.

According to Dr Mary Waiyego, a neonatologist at the hospital and head of the unit, only mothers at the hospital who are in good health and produce excess milk more than their babies in need are allowed to donate milk.

“Our priority is preterm babies whose mothers are not there or have died, preterm babies who are not stable, term babies who are very sick and babies whose mothers struggle to produce milk,” says Dr Waiyego. To qualify as a donor, one has to be a mother admitted at the hospital and as soon as she is discharged she seizes to be a donor. Also, only babies born at the hospital are eligible to get the milk.

“The milk acts as a stop gap measure for the babies who cannot get breast milk as soon as they are born. Once the babies are discharged from the hospital, they are no longer given the milk,” she says, adding that the milk helps with their steady growth and those who are sick recover faster.

Kangaroo mother care

Breast milk is more tolerated by babies than any other milk. “Mother’s milk is the best for the preterm babies as it boosts their immune system with antibodies that help them to develop. It also helps to reduce the risk of babies developing gastrointestinal conditions. The milk also helps the sick, fragile babies to recover faster,” says Dr Waiyego.

The milk has been lifesaving for babies in the hospital. Holding her baby girl tightly onto her chest, 23-year-old Gladys Njoki recalls that she felt unconscious after delivering her baby girl prematurely at 28 weeks at Pumwani.

The baby weighed only 1kg. As the baby was being taken to the nursery, nurses were trying to stabilise her mother’s high blood pressure.

For a whole week, Gladys was not able to see her baby or breastfeed her.

Shantelle Mueni, a donor to the milk bank.

After recovering, she discovered that she did not have any breast milk to give her baby. “The nurse tried to help me express, but there was nothing. The nurse continued giving her the milk from the bank,” says the mother of three, who is full of gratitude.

“I was informed that another mother’s breast milk was being used and it was treated so it was okay for my baby to take.”

For three weeks, her baby fed on breast milk from the bank.

Meanwhile, to help the baby attain the required weight, Gladys is practising the Kangaroo mother care (KMC).

KMC is ensuring skin-to-skin contact between a mother and her baby to offer better thermal regulation to enable growth for preterm newborns. “The baby was too tiny for me to handle. I was advised to hold her always on my chest for her to grow,” she says, adding that none of her other children was born at such a low weight.

“I sleep with her on my chest, sit with her on my chest. The baby has to be warm all the time. I have been here for close to two months and I am hoping to be discharged soon when my baby attains 1.8kg. She now weighs 1.7kg.”

The World Health Organization recommends exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months. However, in cases where the breast milk is not available, WHO recommends donor milk for the babies.

According to WHO, premature babies have a higher chance of survival if fed with breast milk instead of formula. “There is no established system of collecting breast milk outside the hospital although there are discussions along that line. So, all the milk donated to the unit is by mothers who have delivered at the hospital,” notes Dr Waiyego.

The unit is part of the hospital’s lactation support centre and is run by a nurse/counsellor, a nutritionist and an assistant nurse.

So far the milk has helped 325 babies. A total of 577 mothers have donated their milk to it.

Beatrice Marube, the head of Nutrition at Pumwani hospital, says mothers in the postnatal and newborn units are taught about hygiene and healthy feeding and during these sessions mothers with excess milk are identified.

“As we educate the mother on how to breastfeed, we identify those who have excess milk then we talk to them about donating it to other babies,” she says. “These are mothers who can breastfeed with ease and have a lot more milk than what their babies need.”

Consent form

The mothers who agree to donate their milk voluntarily are referred to the lactation centre, where they meet the hospital counsellor who is also a nurse.

The challenge, says Ms Marube, is that some mothers are discouraged from donating by cultural beliefs that advise against sharing their milk with other babies. “This is a new thing for most of the mothers and it takes courage for them to agree to donate their milk,” she adds.

The number of donors at the hospital at any given time depends on how many mothers are in the postnatal and newborn unit. The hospital admissions ranges from 70 to 100 mothers.

The mothers in the newborn unit can stay for up to six weeks, depending on when the baby is fit to be discharged. Therefore, those who are donating the milk can do so during this time.

For a mother to donate her milk, she is screened for Hepatitis B, C, HIV/Aids and syphilis and when she tests negative she is referred to the lactation unit to donate milk. The mother should also not be on any strong medication at the time they are donating milk.

At the lactation centre, the donor meets the counsellor and is asked to fill up a questionnaire about her general health. “The questionnaire helps us know if the mother has any pre-existing condition like tuberculosis, had blood transfusion or is taking any medication,” says Njau, the counsellor.

Beatrice Marube, head of Nutrition at Pumwani hospital, assists a donor to express milk to donate to the unit.

She adds that as the mother fills up the questionnaire they talk to them to ensure she understands why she is donating the milk and that she is ready to volunteer.

The mother then signs a consent form indicating that she has agreed to voluntarily donate her breast milk to another unknown baby at no cost and at no point will she claim it.

After filling in the questionnaire and the consent, the mother’s details are entered into the donor’s registration book. These details include the date, a registration number given to her and the time of donating the milk. The mother then proceeds to the expression unit where she is assisted to express her milk by the nutritionist in charge.

“We work as a team, from the ward to the lactation centre. Here, we have to make sure that the milk is expressed under hygienic conditions and that the mothers have no struggle while expressing the milk,” says Njau.

Donor’s ID

The milk bank has three expression units with electrical breast pumps. “We have sterile bottles measuring 120ml that mothers use to express their milk under hygiene conditions, one mother in each unit at a time,” says Marube, the head nutritionist.

After expression, the mother’s raw milk is divided into 50ml, the bottles labelled with a red sticker bearing the date the milk is expressed, the expiry date (a date six months from the time the milk is expressed) and the donor’s ID and is then taken to the fridge. The unit has two fridges and two freezers (for raw milk and for ready to use).

A sample of the raw milk is then taken to the laboratory for testing to check if it has any microorganisms (bacteria and viruses) that can contaminate it.

From the fridge, the raw milk is put into a pasteurisation casket. “Each casket holds a total of 18 bottles, with one bottle acting as a control. However, each pasteurisation session has to have 36 bottles of milk,” says Njau.

The milk is then pasteurised at 62 degrees centigrade for 30 minutes then it suddenly cools to four degrees centigrade. This is an automated process. A chip in the pasteurising machine records the process on the computer, which helps track the process of pasteurisation.

A sample of the pasteurised milk is again taken to the laboratory for testing to ensure that it was not contaminated during pasteurisation process.

If the test results are negative, the milk is labelled with a green sticker (ready to use) and stored in the freezer at -20 degrees centigrade. “The milk is only removed from the freezer on need basis every morning and it is thawed in the fridge for 24 hours before it is dispensed to the babies,” adds Njau. “Before the baby is given the milk from the fridge, it is warmed in hot water.”

Record every detail

When the milk is dispensed from the unit, the details of the donor are again entered into a dispensing register and the baby’s details are entered into a recipients register book. The details of the nurse dispensing the milk are also recorded. “We record every detail for the purposes of tracking. In case a baby falls sick or the milk was spoilt, we can check for the details in our records,” says Njau.

According to Dr Waiyego, the establishment of the milk bank was informed by a study conducted in 2016 that showed that 90 per cent of the participants were for the idea and 80 per cent were willing to donate their milk. Also, 60 per cent of the women had no problem with their children being fed on the donated milk.

Kenya is the fourth country in Africa and first in East Africa to come up with this intervention for mothers who are not able to breastfeed their babies. Others are South Africa, Mozambique and Cape Verde.

Kenyatta National Hospital is also looking into establishing a milk bank. Dr Waiyego says other countries in the region, including Uganda and Tanzania, have shown interest in setting up a milk bank. Kenya’s reference country for the unit was Scotland and South Africa.

Special correspondent