I raped because my commander did it first: Tales from warzones

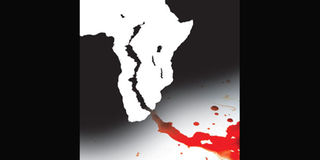

War’s oldest and least punished crime is growing in scale, and Africa is bearing the brunt of it all.

What you need to know:

“Too many of the places I have visited as Secretary of State bear the scars of a time when rape was used as a tactic of oppression and intimidation.

Indeed, sexual violence in conflict is one of the most persistent and most neglected injustices today. As my country’s top diplomat, ending this cycle of violence is a critical mission.

The first step is to begin treating sexual violence in armed conflict as a major international crime. It is not and cannot be seen as an inevitable consequence of conflict. Nor is it a simple infraction of a country’s penal code.

The next step in this overdue process will be persuading every government to deny safe haven to those who commit these vile acts. We must communicate a unified stance with a single, loud voice:

There is no place in the civilised world for those who commit acts of sexual violence. We must declare in unison: ‘They can’t run and they won’t hide here.”

John Kerry, US Secretary of StateState

Rape and sexual violence in conflict zones in Africa have continually been used as a tactic of war.

Often overlooked as just one of the small prices civilians have to pay, the staggering statistics tell a shocking story; that this is a growing epidemic that is finding acceptance in many warzones.

Often described as war’s oldest and least condemned crime, sexual violence in conflict zones mostly goes unreported because the victims fear retribution and banishment from their spouses. For this reason, it is difficult to settle on accurate data.

However, the World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates that 150 million women and girls are raped annually in conflict zones worldwide, while an estimated 73 million men and boys suffer the same fate.

In April 2013, the United Nations reported 211 cases of sexual violence in Mali over a period of 16 months, including rape, sexual slavery, forced marriage and gang rape.

A meeting in London between June 10 and 13, dubbed Global Summit to End Sexual Violence in Conflict, brought together government delegations, NGOs, experts and sexual and gender-based violence survivors from over 145 countries.

“Too many of the places I have visited as Secretary of State bear the scars of a time when rape was used as a tactic of oppression and intimidation.

Indeed, sexual violence in conflict is one of the most persistent and most neglected injustices today. As my country’s top diplomat, ending this cycle of violence is a critical mission.

The first step is to begin treating sexual violence in armed conflict as a major international crime. It is not and cannot be seen as an inevitable consequence of conflict. Nor is it a simple infraction of a country’s penal code.

The next step in this overdue process will be persuading every government to deny safe haven to those who commit these vile acts. We must communicate a unified stance with a single, loud voice:

There is no place in the civilised world for those who commit acts of sexual violence. We must declare in unison: ‘They can’t run and they won’t hide here.”

John Kerry, US Secretary of State

Hosted by the UK’s Foreign Secretary, William Hague, and movie star Angelina Jolie, who is also Special Envoy for the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, the gathering heard that warzone rape thrives on silence and denial.

“The stigma harms survivors and causes feelings of shame and worthlessness,” said Jolie. “It feeds ignorance such as the notion that rape has anything to do with normal sexual impulses.

“Most of all, it allows the rapists to get away with it. They feel above the law because the law rarely touches them, and society rarely touches them.”

Women who have experienced sexual violence in conflict need help to get their lives back on track in the form of compensation for the loss of land and livelihoods caused by fighting, as well as psychological support, according to Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka, the head of UN-Women.

While men also experience sexual violence during conflict, more than 70 per cent of reported cases relate to women and girls, says Mlambo-Ngcuka.

The impact of fighting is felt on multiple fronts for women — physically, emotionally and economically. However, when conflict ends, they often miss out on compensation.

“Combatants get compensation, even if they are not fighting on the side of the national army,” says Mlambo-Ngcuka. “Those who kill get support. Those whose lives are ripped apart don’t.”

Few women are lucky to see justice served on their attackers. Only recently — in May — did a military court in the Democratic Republic of Congo sentence two soldiers to life imprisonment over rape in Minova.

However, 13 senior officers also accused in the mass trial were acquitted for lack of evidence.

“We must send a message around the world that there is no disgrace in being a survivor of sexual violence, that the shame is on the aggressor. We need to shatter that culture of impunity and make justice the norm, not the exception, for these crimes. We need political will, replicated across the world, and we need to treat this subject as a priority. We need to see real commitment and go after the worst perpetrators, to fund proper protection for vulnerable people, and to step in to help the worst--affected countries. We need all armies, peacekeeping troops and police forces to have prevention of sexual violence in conflict as part of their training.”

Angelina Jolie, special envoy for UNHCR

Liesl Gerntholtz, executive director of the women’s rights division at Human Rights Watch, agrees that economic justice for women is paramount.

“Women want justice, of course they do, but they want many other things. They want jobs so they can leave their abusive husbands; they want to be able to educate their kids. Maybe then they might want justice.”

According to a 2013 UN report on high-risk conflict zones, African countries like Mali, Ivory Coast, Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of Congo, Somalia and South Sudan are the most dangerous places for women to live in.

The report, however, barely scratches the surface in documenting the extent of rape in these conflict zones.

In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, for instance, at least 200,000 victims have been reported since 1998; while between 100,000 and 250,000 women were raped during the three months of genocide in Rwanda in the 1990s.

UN agencies estimate that more than 60,000 women were raped during the civil war in Sierra Leone between 1991 and 2002, while Liberia reported that more than 40,000 women had been victims of sexual violence between 1989 and 2003.

Here, the rape hotspots of the continent:

SOUTH SUDAN

Sexual violence has hit an all-time high here since fighting between two ethnic groups, the Dinka and the Nuer, erupted in December.

Tens of thousands of women and children in refugee camps in Juba are being raped by government soldiers and rebel forces alike. Jane, a war victim in South Sudan, remembers the night they came for her friend:

“The four men all raped her. She was screaming until she lost her voice. When they finished, they started arguing whether to finish her off or leave her. They finally killed her. They fired three bullets to her chest, and then left. I stayed in my hiding place for almost four hours, clutching onto my son.

“I was protected by God. They did not find me. God always plays his part when things get difficult. My son never screamed. I thought he would cry and give us away but it didn’t happen.

“In our village alone, 31 women were raped, and seven of those were killed immediately after, while others died of bleeding. The same story is happening in Bor, it is like a revenge war where you go and do the same thing that was done in your hometown.”’

UGANDA

Uganda may be peaceful most of the times, but the Lord’s Resistance Army rebels have made life unbearable for some people here.

Esther Atim, 20, is one of them, and narrated her story to a global summit on sexual violence in London earlier this month.

Atim was kidnapped at the age on nine from a village in Kaberamaido District in eastern Uganda in 2003. She was repeatedly brutalised and raped for three years by the rebels belonging to the LRA.

She says that after crossing into what is today known as South Sudan, she was put in a tent with other children and raped by men of all ages.

“I cannot count how many times I was raped in Sudan by the LRA rebels,” she said. “Rape was on a daily basis. We were taken like slaves with ropes tightly tied around our waists.

“Our clothes were all torn. We were moving barefoot in cold, in rain, in sunshine. We walked through big bushes. We crossed lakes, rivers and swamps. There was no food, no water.

“If you wanted water, you would force a fellow child to urinate so that you could drink. The children were so thirsty they would threaten to kill their fellow captives if they could not urinate… I had mental problems. I would get nightmares. I would feel like killing somebody.”

RWANDA

This testimony from Stephanie, a Rwandese victim of rape during the genocide in the 1990s, tells it all:

“The war started in 1990 in my hometown. My parents were among the first to be displaced. With the spate of massacres around, we were forced to leave our towns and we had to survive in camps.

“One day we needed provisions and made arrangements with the men who drove trucks to Bukavu. On the road, the guys started acting like the truck was spoilt. ‘We can’t move,’ one said.

“I trusted him, though I did not know him by name. Then he approached me and barked: ‘If you want to live, come here.’ In that instance I recalled what had happened in my village.

“I did not want to die here, so I followed his instructions. What followed has never been easy for me to describe. I cannot count how many times... in one night... the whole night. Whatever happened to me will only be know to me.

“I was suffering but I acted like nothing happened. When you talk about consequences, the effect of rape is with me on a daily basis. I think I will be with it forever.”

EGYPT

A 2013 United Nations report titled Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women found that 99.3 per cent of Egyptian women have experienced some form of sexual harassment.

Advocates in Egypt reveal that sexual harassment is the norm in Egypt and an everyday reality that the average Egyptian woman has to deal with on a daily basis.

Earlier this month, Cairo asked YouTube to pull down a video of a woman being sexually harassed in Tahrir Square during a rally supporting the country’s new president, Abdel-Fattah el-Sissi.

While sexual harassment incidents have been the norm here, mob assaults have drastically soared in the three years of upheaval since the ouster of former president Hosni Mubarak.

The woman captured in the video is not alone; several women were reported to have been assaulted during the inaugural celebrations in Tahrir Square in the capital.

During protests that led to the ouster of President Mubarak, the Operation Anti-Sexual Harassment Assault Initiative in Egypt documented 186 cases of mob sexual assaults and rape in just one week.

DRC

In the Democratic Republic of Congo, the United Nations says that 764 people — 280 of them children — were victims of sexual violence between December 2011 and November 2012.

These are excerpts of confessions from Congolese soldiers who were part of a group that attacked Minova town on the shores of Lake Kivu in the Democratic Republic of Congo on the night of November 22, 2012.

At least 97 women and 33 girls — some as young as six — were raped over the two-day rampage pitting Congo’s armed forces and M23 rebels.

“We found women because they can’t escape. You see her, you catch her, you take her away and you have your way with her. Sometimes you kill her. When you finish raping her, you rape her child. We don’t care about the child’s age. After raping the child, we kill them too. When we rape, we feel free.”

“The commander gave us an order and he was the one who started to do it. There was shooting everywhere. He told us to surround him so he wouldn’t get shot. Then he started raping. He told us to go and rape women.”

“We’d lost all hope, we weren’t thinking like human beings anymore.”

“It was at night, we arrived here after crossing the bridge. It wasn’t as though you knew how many women you were going to rape.”

“I raped because my commander started to rape first.”