Misiani was true to benga to the end

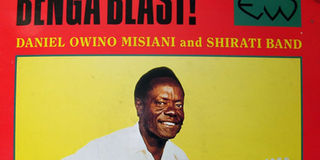

The late D.O. Misiani of Shirati Jazz on one of his album covers. Photo/FILE

What you need to know:

- D.O Misiani was the quintessential protest singer and his legacy is incomplete without the story of his witty, often brave songs that never shied away from the major political and social issues of the day.

- Misiani frequently used the analogy of animals to make pointed commentaries on the social and political state of the country, especially during times of national crisis.

The death of singer and guitarist D.O Misiani in 2006 brought to an end a remarkable career that put Kenya’s most popular music genre on the world map.

Misiani stands out as perhaps the only popular artiste to have remained true to benga in its purest form until the end of his life.

Ethnomusicologist Tabu Osusa, who produced the documentary Retracing Kenya’s Benga Rhythms, argues that, unlike other musicians of the era like George Ramogi and Collela Mazee, who were experimental, Misiani was not musically versatile and relied on raw talent to play only what he knew best — benga.

He often claimed that the term “benga” was adopted from his mother’s name, although the aforementioned documentary shows that the word was first used in a 1963 song by pioneer guitarist John Ogara, long before Misiani himself started playing that style of music.

Daniel Owino Misiani was born on January 22, 1940, in Shirati, near Musoma, in what was then known as Tanganyika. He attended Mukoma Primary School and Ikuzu Secondary School in Tanzania and completed his Form Four at Bungoma Secondary School in Kenya.

During his school days, he would lead the choir and could play the guitar and piano. However, his strict parents did not approve of his musical ambitions, and he also faced harassment from the authorities, who destroyed his first guitar.

When he arrived in Nairobi in 1960, Misiani met another young musician, Daniel Amunga, and together they formed Kasanga Victoria Boys Band in 1963.

After they went their separate ways a few years later, Misiani set up his own band, Shirati Luo Voice Jazz, and recorded their first album on the Sungura record label in 1972. Later, he changed the name of the band to D.O 7 Shirati Jazz Band.

PROTEST SINGER

D.O Misiani was the quintessential protest singer and his legacy is incomplete without the story of his witty, often brave songs that never shied away from the major political and social issues of the day. Misiani frequently used the analogy of animals to make pointed commentaries on the social and political state of the country, especially during times of national crisis.

In 1975, following the assassination of populist politician J.M. Kariuki, which was widely blamed on powerful people in the Jomo Kenyatta Government, he released a song asking what J.M. had done to deserve to be killed and compared the brutal murder to a cat that eats its own kitten.

It was not just the events in Kenya that riled Misiani. The tyranny of Idi Amin in Uganda prompted the singer to warn the dictator that his time was up in a song titled “Wangni to Iringo (This time you will flee).

In the aftermath of the 1982 coup attempt against the government of Daniel arap Moi, Misiani composed Piny Owacho, a song in Dholuo that heaped praise on the Air Force soldiers who led the mutiny. He was arrested by police and locked up for a few days.

He did not spare the Kibaki government either. After Kibaki came to power in 2003 and failed to honour a pre-election pact with the political party led by Raila Odinga, Misiani recorded a song in Dholuo titled Bim en Bim, meaning a baboon will always remain a baboon.

Again, the police arrested the musician and radio stations that had initially played the song suddenly shunned it for fear of reprisals by the authorities.

NO CHARGES

No charges were preferred against him. It was difficult to make any charges stick because he satirised national events in lyrics that were never overtly political; instead he cloaked his messages in proverbs and imagery.

However, those who listened to his music were left in no doubt as to what exactly the musician meant.

The police could only lock him up in for a few days before releasing him. Sometimes, they banished him to his original home in northern Tanzania on allegations that he was an illegal immigrant.

Misiani grew increasingly disillusioned with the country’s state of affairs after he realised that even with the exit of Kanu in 2002, he was still facing persecution for his music under the NARC Government.

So in 2004, he left Nairobi and returned home to Shirati. He died in a road accident near Kisumu on 17 May, 2006, on his way home after a rehearsal with his band.

Misiani wrote love and praise songs for prominent personalities, but it was his political stance that his fans went to great lengths to interpret because, as can be expected, the singer was a master in employing irony and allegory in masking his political views.

“His songs convey meaning at a deeper level,” writes American researcher Doug Patterson in the liner notes for the CD, D.O. Misiani: The King of History.

“He would use a theme such as a verse or parable in the Bible, a prophecy, or an animal parable to allow listeners to interpret the relevant, often political, meaning,” he adds.

D.O. Misiani was the only musician who was consistently a thorn in the flesh of the three regimes in Kenya from independence to his death.

As he once asked: What is wrong with singing about what is going on in our society? If some people are not happy, I can do very little about it.”