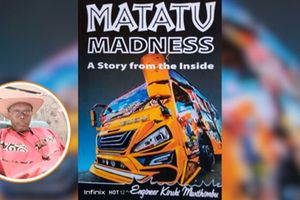

Public service vehicles on the streets of Nairobi on July 24, 2025.

It’s hard to imagine Kenyan urban centres without matatu culture in one form or another. The mwananchi’s mode of transport varies from the modified nganyas in Nairobi, to the vans that are more commonly referred to as “Nissan” ruling other towns, to what are supposed to be 5-seater station wagons that end up carrying up to nine passengers at-a-go in smaller municipalities.

Most probably don’t know where the term “matatu” originated from. According to 254 Matatu culture, this means of transportation began in the 1950s as informal “pirate” minibuses, filling a gap left by the state-run Kenya Bus Services (KBS) for public service transport (PSV).

Matatu is from the Kikuyu language, referring to the fare in early days that would cost three cents; later evolving to mean “thirty cents”.

The three foundations of matatu, nganya or manayangas from around the late 80s to the present are: art, music and style. From the designs of the vehicles, to the graffiti or art work on them, to the sound system and the kind of music played in them, to even the crews that operate them (drivers and conductors) everything has to ooze swag. The motivation is their appeal or attractiveness the youth or youthful passengers.

A man who was a vibrant youth residing in Embakasi in the early 2000s, remembers that even though the nganyas back then were still artistically expressive, they noise level wasn’t quite to where it is nowadays. During those Michuki days, he adds, there were a lot of rigid rules that controlled the matatu industry.

“They were not allowed to have standing passengers. The matatu I used to love taking would play reggae exclusively. The police wouldn’t stop vehicles without cause, even if they had the music playing. The Gen Zs call them nganya but we used to call them nyanga.”

A public service vehicle (PSV) that was deemed to be crème de le crème during its time.

A lady says she was in her prime as a “manyanga-faithful” around 2010. She remembers how the hottest “manyangas” would play hip hop music from artistes like Tupac, Notorious B.I.G, Lil Wayne, and also Kenyan stars like Nameless.

“Every manyanga had its own vibe and music. You knew which manyanga you would board to get a certain feel. They were also known to be the reserve of “cool kids”; you could only board them if you had money, were in high school or campus. From Route 23, Route 44, Route 11, Route 105 – manyangas were the flex. Man, I miss those days,” she said.

She says that in 2015, as NTSA regulations started coming into play, the government became strict on PSVs. “People started making manyangas with lower profiles in terms of music systems, fancy flashing lights following bans that led to the era fizzing out.”

Another man, a resident of Kayole back in the day, remembers how manyangas going to Buruburu, Jericho, Ngong and Rongai had the most rizz.

A public service vehicle nicknamed Opposite on Kimathi Street on July 24, 2025.

“Saccos had not yet been normalised then. They just had the numbers of the routes to differentiate them. Reggae, raga muffin (fast-paced genre of reggae music) and hip hop were the music we would listen to. Also, some Lingala music known as “kwasa kwasa” would be played. The peak period was from around 1998 to 2007,” he remembers.

He decries that the Gen Z nganyas don’t follow the rules like the manyangas would.

“They would get into the stage and follow he queues of matatus and wait. These days, they flout traffic rules a lot. They can even make illegal turns in the middle of traffic.”

He also observes that during his prime, the screens and monitors currently in nganyas weren’t there at the time.

A public service vehicle (PSV) that was deemed to be crème de le crème during its time.

“You just had a sound system with equalisers and lights. People who boarded manyangas were considered to be coming from ‘top families’ in their neighbourhoods; they were considered people of means – manairobians wenyewe.”

He also says that the era of manyanga dominance in these routes started dwindling after traffic rules started bcoming more stringent and brought back order. But he acknowledges that the cycle is back.