Premium

How Caro’s big day ended with police arrests, chaos, and disappointment

As Caro moved around, she would occasionally make or receive a call—loudly, for everyone to hear.

What you need to know:

- All the children had been bought cheap blue T-shirts written “Caro: My Best Aunt.”

- Caro herself was resplendent in a multicoloured long dress, with a massive headgear.

Hayawi hayawi huwa! Yesterday was a big day—my sister Caro’s big day! The day for her dowry payment, and all plans had been made to make it massive. Nothing had been spared.

Caro had been around for weeks, working with my younger brother Ford (a prison warden at Kitui Prisons), and together they had spent days making our home compound look new!

The grass was cut short, the fences trimmed, and all houses had received a fresh coat of paint—or rather, coloured soil. Early yesterday, a big tent hired from MWITWA (Mwisho wa Lami Teachers’ Welfare Association) had been mounted, along with chairs from MWITWA.

Let me not even mention the people. All the children had been bought cheap blue T-shirts written “Caro: My Best Aunt,” while the senior ladies—including my sister Yunia and Senje Albina, were in brightly coloured deras. Caro had asked Ford and I to wear white shirts, but I refused and rocked my stylish Green Kaunda suit instead.

My father was wearing a new blue Kasongo Kaunda suit, the one with big shiny buttons, which Caro had brought him. But the centre of attention, of course, was Caro herself. She was resplendent in a multicoloured long dress, with a massive headgear that seemed to touch the heavens. She had been in the salon the day before, and that morning someone came to do her makeup. Her face was covered in layers and layers of chemicals, while a thick black line—drawn with what I suspect was black Kiwi polish—arched above her eyebrows.

Were this not family newspaper, I would have described how she looked, but for my own safety, I will simply say she looked like a scarecrow. She was all over the place, walking from house to house, greeting everyone and smiling widely. It was clearly a day she had dreamed of all her life.

As Mwisho wa Lami’s CS for Misinformation, Miscommunication and Broadcasting Lies, she had informed every person, every cow, every child, and every tree. By the time I arrived at 9am, the compound was full. Loudspeakers were blasting gospel songs.

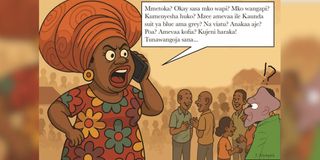

As Caro moved around, she would occasionally make or receive a call—loudly, for everyone to hear:

“Mmetoka? Okay sasa mko wapi? Mko wangapi? Kumenyesha huko? Mzee amevaa ile Kaunda suit ya blue ama grey? Na viatu? Anakaa aje? Poa? Amevaa kofia? Kujeni haraka! Tunawangoja sana...”

The kitchen was a beehive of activity, with cooking happening everywhere—groundnuts being fried, tea boiling, chickens being slaughtered, beef being stewed, rice and chapatis being made. It was indeed a big day.

The tent was full, except for an area marked VVIPs.

I joined the other Mwisho wa Lami men in the tent. There were the usual suspects: Alphayo, Rasto, Nyayo, Tito. We were discussing general topics—maandamano, the economy. Tito tried to discuss a war between Iran, Israel and Russia but no one contributed.

“Where is Hitler today?” Alphayo asked.

“Ever since his cows were stolen last month, Hitler rarely leaves his house,” Rasto said.

“Did he report to the police?” I asked.

“No, I hear he called a mganga who told him not to leave the home at all, the the cows will come back on their own,” said Rasto.

We all laughed loudly at the absurdity

One cow was particularly stubborn

We changed topics, with Alphayo wondering why the President is building a church in State House.

“But what’s wrong with building a church with his own money?” Rasto asked. “Shida iko wapi?”

Tito tried to explain: “It is the Constitution. Section 45 says the State and Church must be separate...

“Then we should change that Constitution!” Rasto interrupted. “Why would a constitution not want a church?!”

As we chatted, Caro was speaking loudly on her phone again: “Mko Shule? Basi mmefika!” She was excited. “Wamefika!” she shouted to no one in particular, and everyone.

We all stood. From the gate, we saw Maskwembe approaching, dressed in a shiny grey Kasongo Kaunda suit with a matching cap and bakora. He was flanked by men in oversized suits, and women in long, multicoloured vitenges. Behind them were four healthy cows—one of them a healthy cross that would surely give lots of milk.

I could not believe what I was seeing. That Maskwembe had brought real cows! I already identified one I wanted to take, just in case my Sh10,000 was not refunded. I would not take it to Fiolina’s place but would keep it, but a cheaper one to go to Fiolina’s. There was only one issue—the cows were difficult to control. The young men handling them were struggling, the cows mooing and pulling the ropes with stubborn resistance.

As tradition dictates, as the guests were taken into the house to enjoy tea, bread, groundnuts and other snacks, their boys handed over the cows to our boys, who tied them to trees. I joined them. One of the cows was particularly stubborn, mooing loudly and dragging the rope. It was like it didn’t want to be used for dowry. But cows are always like that.

While we sipped tea and Tito talked about how Saba Saba would soon be followed by Nane Nane, one of the boys ran in:

“Ng’ombe moja imekata kamba imekimbia!”

We told them to chase it and bring it back. We continued drinking our tea. Later, as we moved into the tent again, I became restless, as the boys hadn't returned.

We heard a car approaching and wondered which big person was this coming for Caro’s dowry. To our shock—it was a police Land Cruiser. Out jumped Hitler himself, pointing at the cows tied near the trees.

“Zingine ndio hizi,” he said. “Hizi ndio ng’ombe zangu ziliibiwa June.”

“Who owns these cows?” the police asked.

Hitler pointed directly at Maskwembe and his people.

“Hawa ndio wametuletea ng’ombe za wizi,” he said

The police moved to arrest Maskwembe. Cries from the women and protests from my father fell on deaf years. My brother Ford tried to intervene, saying he was also an officer—but they told him a prison warden is not a police officer. They bundled Maskwembe and two of his men into the Land Cruiser—plus two of the cows!

“Daktari wangu aliniambia nisijali, ng’ombe zitajileta zenyewe,” Hitler said proudly. “Sasa zimejileta!”

In the confusion, no one noticed that Nyayo had disappeared. Maskwembe’s entire group fled. My father told them to go back with the one cow that had not been taken: “Sitaki vitu za wizi!”

Caro vanished too—into the house, where she has been crying since then. Word of the drama spread across Mwisho wa Lami like a wildfire. An hour later, the police returned and arrested Nyayo, Tito, and Rasto’s grandson Juma—they were allegedly the ones who had sold the stolen cows to the person who sold them to Maskwembe. They had a case to answer.

Despite my usual dislike of Caro, I truly felt sorry for her. And for myself—for now the cow I wanted to keep was gone, and so was my Sh10,000 contribution.

So, whatever you do today, please spare a thought for my sister Caro, whose dowry day turned into a full-blown crime scene.