Premium

How Saphire’s sacking has put my life in danger

I doubted Saphire even knew he had been dismissed.

When we finally let Saphire go, I knew not everyone would be happy. Of course, I expected Saphire and his family to complain, but I thought everyone else would understand why we took the actions we did. After all, was it not obvious what Saphire did? Or did not do?

And honestly, I wasn’t worried about his “friends,” because Saphire has none. Despite being a professional drunkard, he is very mean. He buys no one alcohol, not even a small tot, so you can’t say he has friends.

Didn’t everyone know that Saphire rarely came to school? And even when he did, he never taught? Didn’t everyone know that his classes were abandoned like an unfinished mud house? Even in the village, people knew Saphire never attended to any social obligations — he never visited the bereaved, he never contributed to funeral expenses, never helped dig graves, and he never helped pay fees for any needy child.

Above all, Saphire was not a role model. Yes, parents use him as an example to their children, but as a bad example. As soon as word spread that Saphire had been sacked, I was shocked at the reactions.

Like I mentioned last week, I doubted Saphire even knew he had been dismissed. When we tried to inform him, he was either missing or too drunk to understand anything.

His mother was told, but she thought it was just another suspension — the kind he had collected like school fees arrears over the years. She promised to tell him, but I highly doubt she did.

Last Wednesday, Saphire appeared at school. True to form, he arrived after 10am and studied the timetable as if it was something he had ever followed in his entire life. Then he walked straight into class.

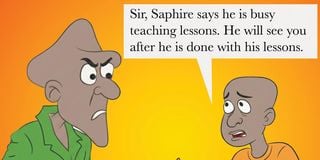

When I heard this, I sent a student to call him. The boy returned and reported: “Sir, Saphire says he is busy teaching lessons. He will see you after he is done with his lessons.” He never came. Instead, he roamed around, even joining other teachers for lunch — despite never contributing a cent to the lunch club. I called him to my office.

“Do you know you are now a stranger in this school and should not be in any classroom?” I asked after closing the door.

“Why?” he asked, shocked.

“Because you are no longer a teacher here,” I told him. “We tried everything, but you made it impossible. In fact, Saphire, you sacked yourself.”

I expected him to shout, argue, and maybe even swing a fist. But he just opened the door, walked out, and left the school. For the record, he didn’t pick anything from the staffroom because he didn’t even have a locker.

As soon as he left, I convened an emergency staff meeting and informed other teachers that we had left Saphire go.

“What?!” exclaimed Lena, her bad hair in tow. “You can’t do that. You will kill the man!”

“That’s so sad, Dre,” said Stella. “Is there nothing we can do to rescue him?”

Even I was shocked that teachers were suddenly defending him. Weren’t these the same people who had always complained about his heavy workload falling on them?

“Really? You people didn’t think Saphire was a liability?” I asked. “How come you are now blaming me when you all know who Saphire was?”

“Dre,” Kuya teacher said, “we’ve had several headmasters here before you. None of them ever fired Saphire. You are the first. This will not go well.”

I ended the meeting and went back to my work. Later, at around 6pm, I passed by Hitler’s, where I am still slowly rebuilding relationships following the small issue of dowry cows.

I didn’t need a calculator to notice how cold people were. Everyone avoided me. I ordered a drink and sat down. Alphayo came a few minutes later. “We’ve just carried Saphire home — he was completely drunk,” he said. “He says you fired him. Is it true?”

“Not true,” I replied. “Saphire fired himself by never coming to school. Everyone knows this.”

“But who reported him? Was it not you?” Alphayo asked, and then walked away muttering, “This will not end well.” As I walked home, people pointed fingers at me. My ex-sister Caro, Mwisho wa Lami’s former Cabinet Secretary for Misinformation, Miscommunication, and Broadcasting Lies, had already spread the story.

She was telling anyone who cared to listen: “Imagine! Head teachers from other clans and villages came here and never fired Saphire. But our own brother has fired him. I am not surprised. This is the same brother who rejected me!”

When I arrived home, I found several people gathered. Saphire’s mother was crying, supported by other women. “What did we ever do to you for you to fire our son?” one woman asked me on her behalf.

“Are you happy now, after making another woman’s child jobless?” another added. When Saphire’s mother lifted her head and saw me, she wailed loudly, stood up to leave, and collapsed at the doorway. The women rushed to hold her. “Devil!” is all she said.

“See what you have done to someone’s mother!” one of the women shouted at me as they left

That night, at around 3 a.m., I heard my animals making unusual noises — cows mooing, goats bleating as if they were in a choir of pain. When I rushed out, I found that some wicked people had come with pangas and slashed several of my beautiful animals. They were bleeding badly. We had no choice but to sell them to the local butcher at throwaway prices.

That next night, I remained on high alert. True to my instincts, I heard more commotion just before midnight. I opened the door slowly to check what was happening. Since it was too dark, I switched on my torch.

“Kimbia!” someone shouted, and I saw two figures sprinting away. They dropped something as they escaped.

I stayed awake the rest of the night. In the morning, I found what they had left behind: a small Jerrican with petrol, some dry grass, and a matchbox. Clearly, they had planned to torch my house. To add salt to injury, clothes that had been hanging on the washing line had also been stolen.

Had I not been restless that night, it would be a different story today. I reported the matter to the police. Their advice? “If you see anyone wearing your stolen clothes, come and report to us.” That was the entire police response!

I would later receive an SMS from an unknown number: “You are lucky to be alive, but we will be back. You must feel how Saphire feels.”

I took no chances. I asked Fiolina to go back to her people, together with Sospeter and Honda. Branton went to stay with his grandfather.

Until the situation stabilises, I will stay alone, on full-time vigil. But one thing is certain: whether they torch my house, finish my cows, or steal all my underwear from the clothesline, Saphire will not get his job back!