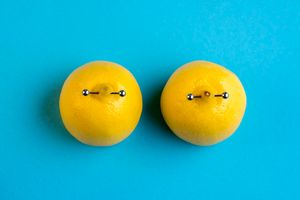

Breastfeeding is often romanticised as a beautiful, and instinctive process.

On April 10, 2021, Faith Thuo, excitedly packed her hospital bag, ready for the arrival of her first child. Inside, she carefully placed the baby rompers, onesies, socks, mittens and her toiletries.

Like many first-time mothers, the prospect of breastfeeding, changing diapers and witnessing her child's first milestones filled Faith with an overwhelming sense of joy and excitement.

Although the journey had its fair share of trepidations, mainly because the 27-year-old had experienced a miscarriage before, things took a different turn for Faith when she was six months pregnant.

“I visited my gynaecologist biweekly, and luckily, everything was well. At six months, I developed a headache which did not go away despite the medications I was prescribed. I was admitted, and the doctor realised that my sugar levels were very high, so they treated me for gestational diabetes,” she recalls.

Also Read: “Breast milk donors came to our rescue”

Several weeks before delivery, Faith had heard from her friends that breasts engorge in readiness for childbirth, but hers were just normal. She assumed maybe they would puff up with milk once she delivered.

Faith Thuo, a mother of two who has never breastfed.

But, because the diabetes was discovered late, Faith gave birth at 37 weeks through a caesarean section. That’s when the struggles with breastfeeding began.

“Every time I would hold him to breastfeed, he would cry hysterically. At night when all the other women and their children were asleep, mine would cry so loudly," she recalls.

Some nurses assigned to Faith’s ward would reassure her that it was normal not to get milk the first three days. She tried again and again. Others felt that the baby was either not latching properly or that she was too stressed, hence the lack of milk.

Some mothers in the ward told her how they had taken some medicine and their breasts began oozing milk.

“I requested the miracle tablet from the nurses, but they were not willing to give it to me. In the dark of the night, I requested that my neighbour help me with just one tablet. I took it secretly and was hopeful that by morning, I would be able to feed my baby. Morning came and went, but I still had no milk.”

Faith encouraged herself that maybe her breasts were not having milk because she had delivered three weeks before her expected due date, so her body was not ready. While at it, her son's sugar levels were being monitored.

"Remember, he was not feeding so at some point, the sugars dropped drastically, so they picked him twice a day to give him formula.”

Trying everything possible

After three days, Faith was discharged, although she still had no milk. As soon as she got home, she began alternating between eating porridge, bone soup, and hot chocolate instead of tea. She also ate cereals, such as black beans, to increase her milk supply.

“I would eat and drink regularly but because I was still cautious of my sugar levels, I watched my quantities,” she recalls.

Just when she was about to give up, another mum gave her more ideas to try but by day five, she still had no milk and the baby’s cries were becoming too frustrating.

“One evening, I told my husband to rush to the nearest shop and get baby formula because I felt the boy would die of starvation. We fed him and the boy calmed down and slept, so clearly, he had been hungry,” she says.

Faith still tried to breastfeed again. She would try to latch her son but he would cry all the more.

“I would get so devastated, wondering how am I mum, who is not able to quieten my child. The norm is that when a child starts to cry, it is given to the mum to breastfeed. But in my case, that did not help. I was so stressed. I would hand over my son to my househelp, and he would go quiet. Oh my God, the thought that she could do a better job at calming my son compounded my frustrations.

Still, Faith refused to give up. She held onto the thought that her milk production was delayed since she delivered three weeks early.

“Maybe my body wasn’t ready, so let me wait for two more weeks then I will get the milk,” she convinced herself while feeding the baby on formula and massaging her breasts with hot water to stimulate the glands.

After two weeks without milk, Faith went back to the hospital. Most of the doctors she saw could not understand why she had no breast milk. However, she found her silver lining—a gynaecologist who was willing to walk with her till she got milk and who greatly encouraged her

“Do not give up; let us try this one more supplement,” she kept telling me. We tried everything, from mamalait granules, lactation cookies and teas, fenugreek seeds to prolactin injections.”

Back in the village, Faith's parents had consulted widely and advised her to boil blackjack leaves, then add some honey and lemon and drink. “I used to take that recipe three times a day for five days.”

Faith would try latching her son after every recipe given.

“I cried every time I saw my baby cry when I held him to my breast. He would cry angrily, as if to say, ‘Mummy why are you giving me an empty plate and you expect me to stay on? Why mum?' I cried so much.”

Not to latch

After many tries, Faith changed tack. She began expressing milk from her breasts using a pump.

“I cried when I made the decision not to latch him anymore since all it did was frustrate me. I would see pictures of breastfeeding mums and feel some excruciating pain. It was just not fair. I tortured myself for not being able to produce milk. I let the loud voices that said, ‘anyone who tries hard can breastfeed' overpower me. I blamed myself for not trying hard enough.

“I pumped after every three hours. For all the pumping, I couldn’t even produce half a millilitre of milk. Most times, a pump would be bone dry. On lucky days, only a drop of that yellow liquid (colostrum) would come out. It wouldn’t even reach the bottle for me to give my baby.

“Sometimes I was scared to pump because I felt I was wasting the precious colostrum.

Many were the nights she would negotiate with God.

“Really God, don't you feel like you've passed me through enough tests this entire pregnancy? Is there another trial we could exchange for this? I am willing to take it up! Don't you think it’s too much to deny me breast milk?”

Slipping into depression

Having tried everything and hoping that the foods, recipes, or tablets would solve the problem and bring forth the white liquid, Faith started slipping into postpartum depression.

Her mind would run wild, “Am I a mother enough? How is it that I cannot feed my baby? Is there something I did to cause the milk not to come? Should my baby form a secure attachment with me now that I'm not able to breastfeed?”

Being a mental health practitioner, Faith knew she had to seek help.

Last straw

When the baby was four months old, she went back to the hospital to test her hormone levels. She had exhausted all possible options but still had no milk. Upon testing her prolactin levels, Faith was informed that they were similar to a non-lactating mum.

“At first, I was angry. Confused. Conflicted. I still believed that if I tried more, I would get milk,” she says.

Upon interrogation by the gynaecologist, Faith remembered that one of her cousins had experienced the same.

“That’s when I gave up all the trying. I gave up all the stressful feeding and the unnecessary flasks of porridge. I permitted myself to pack the pump away. That was so difficult. I remember I had to go for therapy,” she shares.

Her husband, who had walked the whole journey with her, affirmed her. He would often tell her, “Do not feel guilty. You have done everything you could. It is not about you but your biological make-up.”

Some family members also accorded her much-needed support.

“My brother-in-law took on the responsibility of buying the baby’s formula for some months,” she notes.

Although some still told her she should reduce her stress levels, Faith says she meticulously picked which advice to follow.

Armed with information about her condition and having resolved in her heart that she would never breastfeed, Faith, now a mum of two, has some advice for other mums facing similar challenges.

“You are not responsible for the lack of milk. Do not kill yourself trying. It is okay to feel the pressure to breastfeed and to do the best that you can, but remember that as long as you are doing your best, it is not your responsibility to have that milk come out. Do not kill yourself with mum guilt for not being able to breastfeed. It has nothing to do with you.”

Like Faith, Kaari Mukami, 27, has made peace with the fact that she will never breastfeed, although the decision was not easy. When she got pregnant last year, she was as elated.

Kaari routinely went for her checkups and shopped for her child. However, the last trimester was hectic for her as her daughter was not positioned well.

Kaari Mukami was diagnosed with hypoplasia a few days after she gave birth to her first child.

“She was in Occiput Posterior Position (OPP), meaning her head was down but facing her abdomen, so the baby's skull was against the back of her pelvis. There was no way I could have a vaginal birth without risking a third-degree tear,” she recalls.

The doctors informed her that her daughter had positioned herself that way because there was not enough room in her womb.

“My body is small, and the baby was big, 3.8 kilos, and tall too. She had to curve herself to fit."

At the postnatal clinics, doctors asked her whether she felt a change in the size of her breasts.

“My breasts were just the normal size, with no discharge and no pain. They are supposed to engorge, but mine were not.”

When she asked whether the feel of her breasts was worrying, Kaari was assured that they would examine her after she delivered because “every mother has different experiences.”

A tired baby

At 39 weeks, Kaari’s cervix dilated but with no contractions. She was rushed to the hospital and was immediately booked for an emergency caesarean section.

“I was nine centimetres dilated and still had no contractions, but my baby was tired."

On December 10, 2023, Kaari welcomed her daughter. She was given about three hours to recover in the ward. The moment she could lift her legs, she was given her daughter to breastfeed so that the colostrum could come out.

“I latched her but when she started suckling, she began crying. Nothing was coming out. The doctor came and pinched my breast, which was supposed to be painful, but I felt nothing. She asked me, 'Have you ever had a nipple crack?' I didn’t even know what that was."

That day, Kaari was given four tablets, and the doctor told her, "After some time, water is supposed to come out but in the meantime, keep on breastfeeding so that your baby can suckle whatever is going to come out.”

Kaari felt like her world was crumbling. She could not cry because her daughter was wailing. She wanted to scream her heart out. She hoped that maybe she was unable to breastfeed because of fatigue.

After two hours, the doctor came back. “Anything?” she asked. “No. My breasts are just the same. No increment. They are supposed to be heavy but they are not. So one day post-CS, the baby was taken to the nursery and was given formula, I was sent to the gynaecologist."

Shattering words

At the gynaecologist's office, Kaari underwent some tests and then she was called in together with her husband.

“Boss, sioni mkiweza kunyonyesha huyu mtoto wenu (Boss I don't see you being able to breastfeed your child). 'Huyu matiti zake haziwezi toa maziwa (Her breasts cannot produce milk). She has a condition called hypoplasia, underdevelopment or incomplete development of a tissue or organ. So, her glands are not fully developed for them to produce milk and there is no way she is ever going to breastfeed at all.”

This news shattered Kaari. She did not speak to anyone for two days, she kept weeping. “Breastfeeding is a way of bonding with your child so what am I supposed to do? I felt like I didn’t deserve to have a child. My mother-in-law feared I would slip into depression.”

In the ward, a fellow mum encouraged her, saying, “Do not cry. Your daughter will turn out okay.”

“That woman gave me courage. She was able to console me."

A week after leaving the hospital, Kaari accepted her fate. The nights had been hard. Her daughter was constantly crying, and sometimes she did not want to bottle-feed.

“My mother-in-law persuaded me to try to pick up my daughter from her cot and bottle feed her instead of letting her cry all night.”

She lived a day and night at a time. She gave away the breast pumps she had bought and slowly took over her daughter's feeding. By this time, word had already gone around that she could not breastfeed, so almost all her relatives were sending in foods they knew could boost milk supply.

“I asked my husband to tell all of them to stop sending in foodstuff.”

Unsolicited advice

In most African communities if you tell someone you have a child, they test you by saying, 'mnyonyeshe tuamini ni wako (breastfeed the baby so that we can believe it is yours). One of Kaari's family members who had visited them prodded why she could not breastfeed and concluded that she (Kaari) did not want to have sagged breasts.

This pierced her heart. “I felt judged because I knew that was not true.”

Now, Kaari has resolved to avoid meeting with friends and family until her daughter turns one. “For the last eight months we have not left Nairobi,” she says.

To fellow mums who are unable to breastfeed, Kaari advises, “Breastfeeding can be a way of bonding with your child but that is not the only way. Let that not make you feel less of a mother. You are a great mother. No matter what happens, he or she is your child and will always need you from time to time.”

wkanuri@ke.nationmedia.com