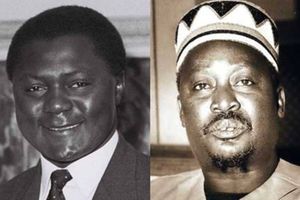

The late Tom Mboya (left) who was gunned down in Nairobi on July 5, 1969.

Those readers of my column in the Sunday Nation will know that I sometimes fantasise about going places with ghosts – an unusual way of writing about Kenya’s history.

The story of the ghost I am writing about now, Tom Mboya, was, for me, the most challenging but also the most thrilling.

This man in a smart blue suit and tie suddenly appeared one afternoon as I was sitting on the veranda of my house.

Fortunately, I was on my own that day, or my wife would have wondered what I was doing talking to myself; as usual, my ghost companion could be seen and heard only by me.

"Do you know who I am?" this ghost asked.

"Yes, I do," I said. "You are Tom Mboya. I am amazed, fascinated and honoured. But why have you sought me out?"

"For one thing, I have heard that you actually enjoy chatting with and writing about ghosts of Kenya’s past. You know, we ghosts who have lived in Kenya, whatever our differences in life, tend to stick together in what, otherwise, is a rather boring afterlife for ghosts. But there are two more reasons why I wanted to meet you.

First, you wrote a book on African Socialism with your colleague, Tom Mulusa, for the Kenya Literature Bureau. I had promised Tom that I would write a foreword, but I was gunned down (in July 1969) before I was able to make good the promise.

Second, I understand that, when helping Michael Blundell (colonial-era farmer and politician) with his memoir, you once said that you thought I might have one day become the first African Secretary General of the United Nations.

In fact, I had begun to feel blocked as a politician in Kenya. Yes, I did have my eyes on a job with the UN. I didn’t really need to be assassinated."

I told Mboya that I was in Nairobi the day he was shot, July 5, 1969, and a couple of days later I went back to the UK after my two years’ secondment at the Adult Studies Centre of the University of Nairobi.

The adult students there were on a one-year course leading to a Certificate of Adult Studies that was equivalent to the secondary schools’ A level.

Most of the students were hoping to go on to a university. On the two courses I taught, one of the set books was George Orwell’s Animal Farm.

"Oh, I know that book very well. I loved it," he said with a chuckle. "And I guess they identified me as one of the pigs who had taken over the farm after turning out the white farmers."

"Yes, they did. Can you guess which one you were?"

"No. Tell me."

"Squealer. The clever one. The one who wrote on the wall ‘All animals are equal’ and later changed it to ‘All animals are equal but some are more equal than others’."

"Really? And who was Napoleon, who took over as leader, and who was Snowball, who was banished?"

"Can’t you guess?"

"Ok. Jomo Kenyatta was Napoleon and Jaramogi Oginga Odinga was Snowball?"

"Yes. Boxer, the hard-working horse, was one of the wananchi, and the dogs were the GSU."

"I suppose the sheep were the KANU followers, shouting “Four legs good. Two legs bad”?"

"And, like KANU, the pigs’ symbol was a cockerel."

"Oh yes, I hadn’t thought of that!"

I also told him that the Luo participants on the course were quite critical of him. They thought he had sold out to the Kikuyu in government. They tended to side with Jaramogi.

"Yes, I can understand that," the ghost said. "My own view was that I was looking forwards and my rival leader was looking backwards – very much a traditionalist. I was keen to play a part in the development of Kenya, shunning tribalism, training young Kenyans who would have leadership roles in the new Kenya, modernising agriculture, establishing more processing industries, increasing exports and creating more jobs."

"At the Lancaster House Conferences, where you took a prominent part I believe, Wilfred Havelock, a member of the KADU party at the second conference, told me that Reginald Maudling, who had taken over as Secretary of State for the Colonies, addressed a critical question to the African delegates.

‘What will your land policy be? Will you, like Tanzania, adopt a state ownership policy or will you opt for private ownership of land?’ Havelock said that there was a unanimous view that it should be private ownership.

"Was he correct?"

"Yes, he was."

"So, when you were the Minister of Economic Planning and Development, why did you call your Sessional Paper 10, outlining Kenya’s economic policies, ‘African Socialism and its Application to Planning in Kenya’?"

"Well, I explained that in my book, Freedom and After”. I argued that the inquisitive instinct, which is largely responsible for the vicious excesses and exploitation under the capitalist system, would be tempered by a sense of togetherness and a rejection of graft and meanness. And I believed that these were the values for which African Socialism stood. Well, I might have been right about the attitudes and ideals of traditional African societies, but I was clearly wrong about the inquisitive instinct being tempered."

"And what do you think of how Kenya is now?"

"It is a much better place than it was in 1969. Of course, some of the problems have been increasing, such as the unemployment rate and the spreading of informal settlements, but there are a number of reasons to be positive – the growth of a productive Kenyan middle class, the growing number of Kenyan professionals in so many different spheres, the energies of the cities, the concern for conservation, especially among the young."

"And is Jaramogi Oginga Odinga a member of your ghost friendship group?"

"Oh yes, and a very active one. We often share a laugh about our old rivalries. And I look forward to telling him about the roles your students assigned us in Georg Orwell’s “Animal Farm”’.