Premium

A Tutu-less New Year, murder in the Cathedral and resolutions

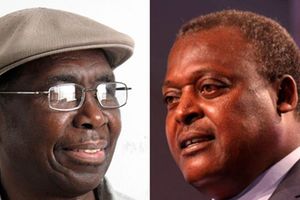

Nobel Peace Laureate Archbishop Desmond Tutu gestures during a press conference about the first 20 years of freedom in South Africa at St Georges Cathedral in Cape Town. The South African anti-apartheid icon, described as the country’s moral compass, died on December 26, 2021, aged 90.

I was just about to wish you a Happy New Year when Desmond Tutu happened, or “dis-happened”, as he might have joked with his unforgettably infectious laugh. The final departure of “Arch” Tutu sent me mulling not only about the life and career of this unique churchman but also about Murder in the Cathedral, a play by T. S. Eliot. I will be telling you presently about its relevance to the Desmond Tutu story.

First, however, let me return briefly to my original intention of wishing you a Happy New Year, and sharing with you two or three of my resolutions for 2022. You may be chuckling, like me, about this, for two main reasons. First, “happy new year” is a cliché, and we should avoid cliches. As for “resolutions”, we know their fate.

Still, happy and prosperous new year. I offer no apologies for the “cliché”, since I mean it with all my heart. In any case, this phrase belongs to what is called “phatic communion”, the kind of communication intended primarily for establishing, promoting and maintaining relationships.

Phatic communion (or affective language) consists largely of apparent cliches. “I love you” is one of the commonest cliches in our relationships.

On to my New Year resolutions, I felt that this year I would borrow viable ones from the thoughts of my acquaintances and friends. I hope that the rightful owners of the sentiments do not mind my poaching from them, or discreetly mentioning their names. In the New Year, then, I will be grateful, I will care and I will smile.

You, my reader, are certainly a major contributor to my gratefulness. Your reading, your response and your sharing with me has contributed a tremendous lot to the mental health and energy that I need to keep thinking and writing. Feeling and saying thank you for such sustenance is a favour I cannot take for granted.

Innumerable favours

There are, however, innumerable favours around us, especially in these unprecedentedly bizarre times, to be thankful for. Our being alive and well, in the face of obvious threats, demands a “thank you”, at least once a day, to the powers that preserve us. I also feel grateful for all the sensible people doing the things that ensure their and their neighbours’ safety.

I got the “care” resolution from my friend and literary colleague, Kingwa Kamenchu. Kingwa shared with us the view that what the world needs most today is caring.

Too many of us hypocritically evade social responsibility through such subterfuges as “minding my own business” or “I’m only an ordinary mwananchi”. Yet, whoever we are and wherever we are, we can see what needs to be done and we can try and contribute to positive change. In other words, resolve to care.

We, however, best care with a smile, according to my long-time friend, Steenie Njoroge, an all-round man of the arts, who is as good with his camera as he is with his drawing hand. He advises us simply to meet everyone with a smile, as I have seen him do all the three-and-something decades I have known him. I need not sing any praises for that beautiful gift of the smile, since we can all feel it either when we give or receive it. I do not smile anywhere near enough for my good and that of those around me, and resolving to smile more in the New Year is a good idea.

This brings us to our departed Archbishop Desmond Tutu. I noted that most announcements of his death emphasised his age of 90 years. It is not unusual these days for people to live up to 90 years and beyond. Maybe the point about Tutu is that he lived militantly that long in a highly hostile environment and with apparently no external protection.

My hypothesis is that Tutu survived that long and achieved so much mainly because of three sterling qualities, one of which was his irrepressible sense of humour, his smile and infectious laugh. The other two were his authoritative moral integrity and his daringly unshakeable courage. The fight for South African freedom was waged on many fronts, including the armed one. Yet the diminutive Archbishop fought the apartheid regime with only his tenacious presence and his implacably articulate tongue.

How he avoided long debilitating detentions, “banning” and internal exile like those of Winnie Mandela, or even direct “elimination”, will remain a topic of speculation.

Victory over apartheid

From what we can see, however, Tutu blunted the weapons of his opponents with sheer uprightness, fearless bravery and articulate witness. His triumphant survival and victory over the evil apartheid system is also attributable to the long tradition of his church’s speaking truth to power, often in the face of dire threats and mortal dangers.

Tutu’s story may be the best-known in that tradition, but there are several others comparable to it all over the world and throughout history. The Murder in the Cathedral play by T.S. Eliot, for example, is based on the real life martyrdom of Thomas Beckett, Archbishop of Canterbury in the 12th Century, who was murdered at the instigation of King Henry II. The two former friends had differed over state intervention in church affairs.

Closer to our times and climes, we have had stalwarts like Bishop Trevor Huddleston, author of Naught for Your Comfort, who was apparently forced out of South Africa because of his opposition to apartheid. He subsequently served in Masasi in Tanzania. Uganda has its own martyr in Archbishop Janani Luwum, murdered by Idi Amin in 1977, for speaking out against the excesses of the General’s regime.

In Kenya, those old enough to remember still share the trials and tribulations of Anglican leaders like Bishops John Gitari and Alexander Muge. “Arch” Desmond Tutu will not lack company in heaven, with whom to share a laugh over the puny excesses of power in this world.

Meanwhile, please, consider joining me in my resolutions of gratitude, care and smiling as we enter 2022.

Prof Bukenya is a leading East African scholar of English and literature. [email protected]