Premium

Culture, nature and a visit to the peace path

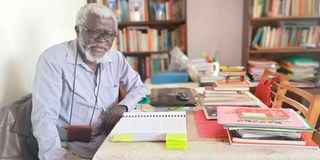

Dr Humphrey Jeremiah Ojwang at his office at the University of Nairobi’s Institute of Anthropology, Gender and African Studies at the Nairobi National Museum.

It is 11:30am and I have just checked into The University of Nairobi’s main campus’ great court. I am here for a noon appointment with Dr Humphrey Jeremiah Ojwang.

My host is a decorated academic. He is a senior lecturer in Linguistics and Anthropology at the College of Humanities and Social Sciences. Aside from this, he is, among other things, a poet, playwright, biographer, social critic and civil rights activist.

But those are titles he donned with pride in his early days in the academy. Today, he has narrowed his focus to research, linguistic anthropology, nature and culture. He is a naturalist, Africanist and ethnographer.

At noon, he calls to announce a change of plan. Instead of meeting either at Mahatma Gandhi Graduate Library lounge or Arziki Restaurant – two well-known installments within The University of Nairobi’s main campus community – as we had earlier agreed, he explains to me why a change of venue is a good idea.

He convinces me to cross over to The University of Nairobi’s Institute of Anthropology, Gender and African Studies at the Nairobi National Museum.

A few minutes later, I knock on the door to Ojwang’s office. He opens the door and ushers me in. He is not alone. In his company is a 26-year old Nasimiyu, whose Master’s degree thesis he had been ploughing through prior to my arrival.

Ojwang’ tells us about Ethiopian highlanders and lowlanders and his disappointment in a section of Ethiopian population that disowns its African (read black) heritage.

Lexicographic Practice

“Ethiopia is Africa. It’s for this reason that we have the AU headquarters in Addis Ababa!” Ojwang declares firmly.

“You have come in at the right time,” he says, as he jumps to his feet and walks over to his bookshelf. He pulls out a number of publications. He parades his two doctoral theses before us.

One is titled ‘A Linguistic Study of Luo Ethnobotanical Terminology in a Culture-Specific Configuration With Implications for Lexicographic Practice.’ He clarifies to us that this is a piece of work in progress – a continuing post-doctoral research. The other one is titled ‘Pedagogical Value of Indigenous Knowledge for Food Security: Learning from Women Farmers in Homa Bay County, Kenya.’ Of the two, the latter is the latest. There are manuscripts, too. Among them are reprints of his Okot p’ Bitek on Trial, a play, and Dusk of Gloom, a poetry anthology whose development, he says, took him 42 years. Then there is A Taste of Freedom – An Authorised Biography of Jaramogi Oginga Odinga.

“A Taste of Freedom is a sequel to Jaramogi’s Not Yet Uhuru. I embarked on this project with Jaramogi’s blessings,” he tells us, waving the written consent Jaramogi gave him. Nelson Mandela wrote the foreword.

Seamlessly, our conversation shifts to one of Ojwang’s favourite subjects. Nature. He tells us of his two homes. One is in Rongo, Migori County. The other is in Koru, Kisumu County. He fishes out a laminated card from one of his desk drawers. ‘Koru Cottage for Nature Studies,’ it reads.

“In my Koru home is a main house and two cottages – for my son and daughter. Since I put it up, I have allowed indigenous trees to grow within the compound without any interference. I have plans of turning the home into a kindergarten where children can commune with nature as they study,” he clarifies.

He digs his hand into another drawer to bring out another laminated card. It has a drawing but no text. He challenges us to look at it and tell him what we think it is. We are at a loss!

“This is a labyrinth,” he declares and says that he is taking us on a tour of the museum

We find ourselves walking down eastern side of the Nairobi National Museum arboretum.

Peace Path

Suddenly, he stops and motions us to turn right to face the entrance to a paved pathway that is lined with stones. He informs us that we are at the entrance to Peace Path. A few metres away, we see a seven-cycle labyrinth made up of carefully-arranged stones. The stones are of different types.

“These stones were sourced from all over Kenya. This ground is an initiative of the Trust for Indigenous Culture and Health (TICAH). The labyrinth is a symbol of Kenyanness, harmony among Kenyans from different lands, ethnicities and tribes. Dr Mary Ann Burris set it up in 2013. It was her way of engraving the memories of the 2007/2008 post-election violence victims,” Ojwang says to us.

We walk along the Peace Path, Ojwang Leading the way.

The ritual begins.

“Leave all your luggage here and kick off your shoes,” he instructs us.

Once we have complied, Ojwang points at a sculpture.

“This is The Eagle,” he says. We look at the sculpture and note a plaque bearing Gerard Motondi’ name.

Ojwang leads us into the labyrinth. He forbids us from uttering a word. It’s a moment for meditation and for bonding with nature. He gently touches The Eagle and signals us to follow suit.

Carefully and in utmost silence, we pick our way, making several turns, to The Eye, Sculptor Charles Kombo’s piece of work. At The Eye, the centre of the labyrinth, we submit ourselves to the four cardinal points of the compass direction – north, south, east and west.

We make our way back to The Eagle. Throughout our sojourn, there is a sculpture that symbolically keeps an eye on us. It is called ‘The Prophet’, Elkanah Ong’esa’s artwork.

“A labyrinth has been used in many cultures for traditional spiritual ceremonies that include healing, meditation and prayer,” Ojwang says as we wind up.

He appreciates that the Nairobi National Museum Peace Path is a peace shrine that offers Kenyans a vision of how they can surmount ethnic, tribal and racial impediments to integration. He, however, laments that not many Kenyans who visit the museum understand the philosophy behind such an establishment as Peace Path.

On our way back, he amazes us with his mastery of semiotics and abstract art.

There is no contention that the sculptures at the Nairobi National Museum foreground and revere and pay homage to womanhood.

According to Ojwang, women’s influence is too critical to a society to be taken for granted. He further recommends the open air riverside ‘amphitheater’ at the museum as an ideal ground for events.

Just when we think it’s all done, Ojwang insists that we exit the museum through the recently renovated Michuki Park. We do just that and that is how we find ourselves at Wasanii Restaurant at the Kenya Cultural Centre.

“Thu tinda!” This is Ojwang’s signature fashion of ending any discourse.