Premium

Kenyatta was behind the bid to ‘block Moi from succeeding him’

President Jomo Kenyatta with Vice-President and Home Affairs Minister Daniel Toroitich arap Moi.

What you need to know:

- Book suggests Mzee backed down only after seeing AG Charles Njonjo was determined to enforce the law.

- The biography has intimate details to support this theory that Kenyatta never wanted Moi to succeed him.

Contrary to the common narrative that founding President Jomo Kenyatta all along wanted Daniel arap Moi to succeed him, a vicious bid to block his vice-president from ascending to power had his tacit support, a new book claims.

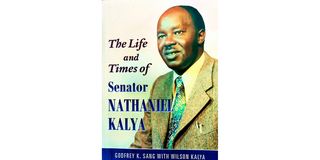

The Life and Times of Senator Nathaniel Kalya, who was deeply involved in the political intrigues of those heady days 45 years ago, says Kenyatta egged on the group known as the Kiambu Mafia that was working to stop Moi in his tracks.

Gerald Nathaniel Kalya was the founding senator of Nandi and later MP for Mosop and Tinderet. Himself not one of the better known of Kenya’s first generation of politicians, Kalya’s tale, told by his son Wilson Kalya and the historian Godfrey Sang, opens a rare glimpse into some of the defining moments of Kenya’s history and the major players of the time.

The biography has intimate details to support this theory that Kenyatta never wanted Moi to succeed him, suggesting that the founding President backed down only after seeing the all-powerful Attorney-General Charles Njonjo was determined to enforce the law that provided the vice-president would automatically take over in the event the Head of State died or was incapacitated.

The authors write of a Change-the-Constitution movement rally in Tinderet in April 1977 to drum up support for ousting Moi as Kanu vice-president and replace him with Dr Taaita Toweett in the Kanu elections that had been slated for later that year. Unlike Moi, a primary school-educated teacher who nevertheless had a commanding presence, the diminutive and eccentric MP from Bureti in Kericho, who had studied at Alliance, Makerere and in South Africa, was not seen as a threat.

“The designated venue was Tinderet Secondary School which had been founded by Seroney. Dr Njoroge Mungai, Kihika Kimani, Njenga Karume and everyone who loathed Moi came to Seroney’s school to front Toweett and ensure that no vice-president would be able to become president without the party’s blessing,” write Sang and Kalya.

“Everyone who spoke castigated Moi for everything, including blaming him [for] the incarceration of Seroney,” they write. Dr Njoroge Mungai appealed to President Kenyatta to release (the outspoken Tinderet MP) Seroney so that he could become the Attorney-General. Kihika Kimani compared Moi to a louse, which he said could be crushed with only one hand.

The authors write that while the speeches continued, Kihika Kimani summoned Kalya and asked him to join him in the headmaster’s office where he had seen a telephone handset. “Kimani took it and spoke in Kikuyu to the person on the other end of the line.

Kalya did not know who it was, until he handed over the handset to him. It was then that he realised it was President Kenyatta! He had been on the line, and it seemed that he had been listening all along! Kenyatta congratulated him for the meeting and told him in Kiswahili, “Endelea na hiyo mkutano yenu – continue with your meeting,” they write.

The change of succession rules, however, was not to be as the Kanu elections were postponed indefinitely. The activities of the Change-the-Constitution crusaders were stopped by Njonjo who issued a terse statement, saying it was a criminal offence for any person to “encompass, imagine, devise, or intend the death or deposition of the President.” Kenyatta followed Njonjo’s statement with his own from State House, saying the government “reiterated the statement by the Attorney-General.”

On the death of Kenyatta in August of 1978, Moi was sworn in as President and would rule for a quarter century, charming, outwitting or crushing his opponents, defying predictions that he would be a passing cloud, or a louse that would be crushed with one hand as Kihika Kimani put it.

These fresh claims bring closer the parallel between the events 45 years ago and those surrounding the succession of Uhuru, Jomo Kenyatta’s son, who has refused to support his deputy, uncannily also a Kalenjin, to succeed him in this year’s election.

The cover of the book 'The Life and Times of Senator Nathaniel Kalya'. authored by Wilson Kalya and Godfrey Sang. The new book claims the vicious bid to block Moi from ascending to power had Kenyatta’s tacit support.

In the years after independence and before he became President, then Vice-President Daniel arap Moi often frequented Nandi, the stomping ground for national political duels, to check Seroney, his challenger for the supremacy of the Rift Valley and a gadfly who had become a thorn in the side of government. Though deputy Speaker of Parliament, Seroney openly spoke his mind, often siding with the opposition of the time.

It was in the crosshairs of Moi and his archrival Seroney that Kalya, an otherwise unconfrontational politician, found himself. Even though Moi was already the preeminent leader of the Rift Valley by dint of his high office, Seroney never quite acquiesced to this, nor did many of his fellow Nandi, who saw him as an uneducated opportunist from the smaller Tugen sub-tribe.

Moi’s ascension to the Presidency complicated matters for Kalya and Seroney. Matters had earlier come to a head for Seroney on October 9, 1975 when outspoken Butere MP Martin Shikuku accused an MP of trying to kill Parliament “the way Kanu had been killed”. When asked by an assistant minister to substantiate, Seroney, then in the Speaker’s chamber, made the now famous phrase: there is no need to substantiate the obvious.

The government found the excuse to finally deal with Seroney. He and Shikuku were expelled from Kanu and detained a week later. In a twist of irony, Kalya, who had earlier lost his Mosop seat courtesy of Seroney, would inherit the latter’s Tinderet after he was asked by a section of constituents to run in the subsequent by-election, a poll he won. But attempts by Seroney to recapture his seat in the 1979 elections after he was released came to naught as were Kalya’s efforts to reclaim his old Mosop bastion.

Moi’s illiterate henchman Ezekiel Barngetuny orchestrated underhand tactics that saw all Moi’s nemeses in the county lose their seats.

“Barngetuny, a meticulous organiser, came up with a massive campaign machinery that was very well-funded obviously using Moi’s money. He also hired goons who posed as campaigners, but who in reality, were detailed to trail the opponents and shout them down during rallies.” These goons roughed up Seroney and Kalya, who withdrew from the race.

That election marked the end of an era in Nandi, with Henry Kosgey, then aged 31, defeating Seroney. Kosgey was appointed minister, the first ever in Nandi, and Kalya retreated to his farms in Kitale and Mosoriot where he led a quiet life until his death in 2015 aged 85.

But the book is not all politics. It has nuggets of tickly social stuff such as when at Alliance a lovelorn Kalya, desperate to receive an important message regarding his girlfriend back home, had his friend pushed forward the school clock by an hour to enable him to get out of school ‘legitimately’ and access the railway station at Kikuyu.

“It was difficult to make the appointment since the train would be making the short stop at Kikuyu Station at 3.30pm yet classes ended at 4.00pm. It was school day and there was no way Carey Francis would allow him to go to the station to meet a friend. Kalya explained his predicament to John Cheruiyot. John, who was now a form 2 student, did the most daring thing to help his friend out.”

The future MP for Aldai sneaked to where the school clock stood and set it forward by an hour, enabling Kalya to rush to the station to receive the news he craved.

It took the school administration several days to notice that something was wrong with the school timings, and they adjusted the clock without knowing what had caused the change.

Kalya would later marry his sweetheart, Emily, herself an accomplished politician who served as councillor (ward representative) for years.

The Life and Times of Senator Nathaniel Kalywa, a story of love and intrigue, of struggle and triumph, was launched last Saturday at the Mosoriot campus of Koitaleel Samoei University, a befitting venue in memory of a man who did so much for education as a pioneering teacher and legislator.

Mr Sigei, a former Nation editor, works at the Media Council of Kenya. Email [email protected]