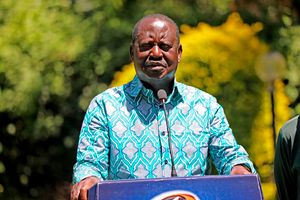

President William Ruto during the Ministerial Performance Contracts for the FY 2024/2025 at State House, Nairobi on November 19, 2024.

As the minutes bled into hours, haemorrhaged into days and flooded into months, 2024 became a wild romp through the Wild West — equal parts magical and terrifying. Even bizarre.

There is no debate that 2024 was a year of disruption and challenge to the status quo in Kenya. Our hopes rose and fell, deflating like balloons. It was the year of unfinished things, maybe even lost things. The year of unmet longings. It was a year of deadly anti-government protests.

Swaggering and swashbuckling, Gen Zs slapped on their goggles and poured into Nairobi streets, some holding up banners and waving them up in the air like flags — the flags of an invading army — there to spread a message of freedom, youth, the anarchy of pure heedlessness and “I dare you”!

Dubbed “Occupy Parliament,” the deadliest protests hit the streets of Nairobi on Tuesday, 18 June 2024. The protests — which triggered a change of cabinet and other seismic realignments in Kenya’s political formation — probably threw the president into uncharted territory. For the challenging year 2024 and probably his most trying moments during the Gen Z protests, President Ruto could write a book entitled “The Trials and Travails of a Kenyan President”.

Every president probably enters office knowing that it would not be an easy job. It must require independence, skill, force of will and destiny to all combine in the right permutations for someone to dare as greatly as to be president. As one writer once quipped, “Being president involves a crash course in mythmaking”. However, during the Gen Z protests, that myth was under threat. And in those fleeting moments, the magic of the presidency — with its extravagant display of power and bravado — seemed to fade, atrophy, like the smell of a passing shower in the hot African sun.

In addressing the protests and generally the whole of 2024, one of President Ruto’s tactics has been to do what great storytellers do to control their narrative: choose where to begin the story he wanted us to hear as his audience, determining what to emphasise, what to tone down as unimportant and what to leave out entirely. We would want to read that book that he hasn’t written yet, one that expounds the poem of us as a nation and explains what was going through his mind in 2024 and especially during the Gen Z protests.

Tyres burning

He can tell us in his book if the word Gen Z reverberates, echoes — conjuring up images of cars shuttering, tyres burning, tarmacked roads littered with stones. During the Gen Z protests, there was a foreboding in the air, a chill like the onset of the flu, an apprehension of sickness, a change in the season, what American writer Joan Didion would have described as a period of “the shadows lengthening… the honeymoon over — the end of promise, the dwindling of the days, the inevitability of the fading, the dying of the brightness”.

President Ruto can tell us whether he felt that his life was framed in the before and after the Gen Z protests: before, he was going on with his job after winning the presidency with some level of protests but not as deadly, and was probably less worried. After, of course, has the dystopian feeling of the violence and loss of lives that ensued.

One of the chapters in the president’s book could be the evening he addressed the nation after protesters stormed Parliament, setting part of it aflame. As if unaware or unconcerned about President Ruto’s predicament, Nairobi moved on, the city probably looking faraway and almost celestial, a charming kingdom whose beaming towers rose defiantly into the dark sky as if they had a rendezvous with the stars — through the lingering teargas smoke, with the street lambs ablaze with the evening lights and probably a lonely car zooming through an empty city, headed toward an unknown destination, the scared driver speeding like a demon.

As he spoke to the nation from a State House podium that was brightly and fluorescently lit, his face like a threatened aristocrat, the president looked both brave and subdued: less “I am your president, hear me roar,” and more “I am trying to figure this out, hear me whisper”. Did he ever feel misunderstood and misrepresented? Did he ever feel alone and adrift in the sea of solitude? Did he feel sorry for himself? Does a president ever feel sorry for himself, sometimes feeling both conspicuous and invisible, like the rest of us? What keeps him awake at night? What perspective does he want to tell?

He can tell it all in his book. He will have the opportunity to give us the context in which he makes the complex decisions he needs to. Maybe that will give us a better understanding of what he faces daily and why he makes the decisions he does. That will probably elicit more empathy from more people.

The writer is a book publisher based in Nairobi. [email protected]