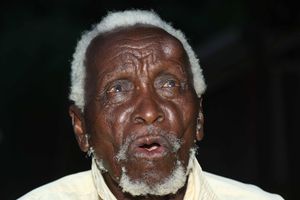

Mr Joseph Muthee, author of ‘Mau Mau Detainee.’

Kenyans need to read the story of one Joseph Muthee. For, Muthee’s story of a horrifying reminder of what could have been in this country.

The story told in Mau Mau Detainee (2023; originally published as Kizuizini) is about a lost chance to build a nation.

If the dreams of the Mau Mau had been realised after 1964, sixty years on, today, Kenya would most likely be a much better place than it is today. Why?

Isn’t it ironic that so many years since the end of colonial rule in Kenya, millions of Kenyans are still landless?

Isn’t it shocking that there are squatters in Nyeri, the epicenter of the Mau Mau uprising? Shouldn’t it be mortifying to Kenya’s political leaders that since 1964, there really has been no attempt to appease the spirits of those who gave their blood, bodies and lives in the struggle for independence from the British?

How can the cries for compensation by the progeny of the men and women who abandoned their daily lives because of unbearable exploitation and oppression by the colonialist, and chose to fight for the freedom of the rest of their communities still be so loud in Kenya today?

The one reason Kenyans should seriously consider addressing the Mau Mau question is because this struggle wasn’t a Kikuyu struggle alone.

In fact, Mau Mau is today a metaphor for a bigger national struggle since the colonial times to date for justice and economic freedom. Mau Mau stands for the desire of an absolute majority of Kenyans for a decent life.

Reading Mau Mau Detainee, one is powerfully reminded of this search for a decent life when Muthee narrates how he ended up being born on a colonial settler’s farm.

His grandfather sought to escape the drudgery of living in the African reserves where the settlers usually got free labour.

The old man did not want his daughters and sons to toil forever in the reserves. He consequently decided to live as a squatter on the settler’s farm.

Muthee would be born on that farm in 1928 and only leave it when he got arrested and detained on suspicion of being Mau Mau in 1954. How did he get back to the settler’s farm?

Again, like his grandfather before, he was searching for a decent life. This is what he says, “… I dropped out of school … thus ending my formal education.

In 1943, I went back to the farm where I was born and requested Captain C. O’Hagan to employ me, but he told me: ‘Although you know how to read and write, and you speak English very well, I’m afraid I can’t employ you because you are still too young.’”

He would be employed two years later at “a starting salary of four shillings a month on the premise that, if I performed my duties well, he would make me a clerk to supervise dairy matters.”

Muthee would work diligently for Captain O’Hagan for 10 years as a labourer in the dairy section of the farm till 1954 when he got arrested. Thereafter, Muthee would end up in several d

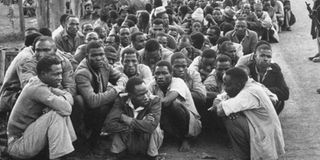

Some of the of the hundreds of Mau Mau suspects who were rounded up in Nairobi after the Lari massacre of March 26, 1953.

etention camps for Mau Mau suspects. There was the hard labour at MacKinnon Road Detention Camp, which included building roads, breaking stones and painting.

Then the unbearable weather of Manyani Detention camp where the colonial government attempted to ‘reform’ the detainees, who had never really been formally charged for any crime.

From Manyani, Muthee found himself on the shores of Lake Victoria, at Kodiaga Prison. From Kodiaga, the detainees were sent to Mageta Island in Lake Victoria.

Life was never easy on Mageta Island. Riots by the detainees for better living conditions would be brutally suppressed.

How many men died in Mageta no one knows. Death was always hovering around. It could be beatings from the guards. Being shot whilst attempting to escape.

Crocodiles

The lake's crocodiles might not have scared some men, but how many drowned because either they could not swim or the wind was just too strong for them, we shall never know. Muthee himself nearly lost his life while swimming.

What hopelessness did the men on Mageta Island have to live with daily, not knowing when they would leave the island or when the freedom they sought would arrive?

This is why the story of Mau Mau is the story of all Kenyans. Men like Muthee got to know the climes and peoples of other regions of Kenya due to detention.

In a file picture taken in October 1952 soldiers guard suspected Mau Mau fighters behind barbed wire in the Kikuyu reserve at the time of the Mau Mau uprising against British colonial rule in Kenya. PHOTO | AFP

They met other men (and women) who did not speak their language, who ate different foods from the ones they grew up eating, had different religious beliefs and practices, behaved differently culturally, but all wanted the kind of freedom that had motivated Muthee and his people to fight the colonial government.

Mau Mau Detainee is not just a retelling of the story of the struggle in Central Kenya. No. It is a close account of what colonialism did to millions of Kenyans.

Colonialism institutionalized theft of land that was deemed unoccupied by the locals. It then stole labour, forcing thousands of young men (and sometimes women) to work on farms and in industries at no pay or survival wages.

These two processes transferred wealth from many Kenyan communities into the families of a few settlers. Colonialism then deliberately established a local class, maintained and defended the settlers’ privileges, including clerics, askaris, clerks, chiefs etc.

When the locals attempted to resist the occupation of their land and theft of their labour and wealth, exile was imposed on them. Husbands left behind wives; fathers children.

Some mothers and their children would never see their husbands and fathers again. Some people returned maimed; others deranged. Most came back to poverty, with their lands stolen, sold or appropriated.

Colonialism would later even set the conditions of return of some of the land: willing seller-willing buyer arrangement. Where the government was willing to buy, it would be lent money to buy back land that belonged to the locals so that it could sell it back to the locals. Irony does not tell the story of Mau Mau and the struggle for freedom in Kenya.

Mau Mau suspects are rounded up in Kenya.

The government of Kenya still pays pension to colonial-era government officers. What did the Mau Mau fighters and detainees get from the post-colonial government? What do they get today?

The story of Mau Mau should have been framed as a national story; a national struggle for freedom for all Kenyans. No Kenyan would deny the suffering of the people of Central and Rift Valley Kenya, especially the Kikuyu. But even among the Kikuyu, there were those who suffered more than others.

To reduce that struggle to a localised and regional resistance as has sometimes been done by politicians and commentators, is what has robbed the collective of suffering Kenyans, especially the Kikuyu, the moral high ground to contest, resist the narratives of those who collaborated with the colonialists, and then stole the fruits of independence.

Even after independence, millions of Kenyans in some regions would face marginalisation or sometimes total exclusion from the central government. Their stories are not dissimilar to the Mau Mau story.

There were thousands of Kenyans then who were not living in the Rift Valley and Central Kenya but who lived through the racism, oppression, economic exclusion and violence of colonialism.

There are still millions of Kenyans today who face these very same problems. The Mau Mau story, as told by Joseph Muthee in Mau Mau Detained is their story as well.

Mau Mau Detained will be launched at the University of Nairobi on September 10, 2024.

The writer teaches literature at the University of Nairobi