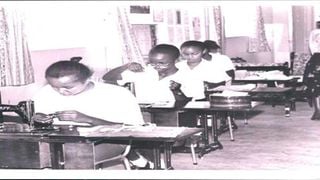

A home science class at Precious Blood School in Nairobi at the start of 8-4-4 in mid 1980s.

| File | Nation Media GroupNews

Premium

Moi’s blunder that took shine off 8-4-4 system developed by Canadian scholar

What you need to know:

- Education experts recommended that the system be implemented slowly and carefully, one year at a time.

- One afternoon, Moi announced that the 8-4-4 system would be implemented immediately, discarding a well-thought plan.

At the National Archives in Nairobi, the Mackay Report that recommended the 8-4-4 system is still a secret document. It is kept at the strong room, and not accessible. The last time I asked to see it, I was informed that the key to the strong-room, where the Mackay files are kept, got lost.

The story of 8-4-4 system, and the politics around it, is still shrouded in mystery – and we might never know why President Moi went for this system of education and whether he was influenced by some Canadian scholars; to be precise, Dr Colin Mackay.

It is also still unclear whether the 8-4-4 system had anything to do with the Canadian funding of technical education in Kenya, though there are some pointers towards that direction. As the government starts to dismantle the 8-4-4 system, and replace it with the Competency Based Curriculum, it seems to be connected to the efforts of the University of New Brunswick’s educationists.

But that will come to light if we get a chance to scrutinise the Kenyan documents held by the university pertaining to the technical training of Kenyan teachers and building of Kenya Teachers Training College in Gigiri, Nairobi.

Let me tell you a story: Before the death of Jomo Kenyatta in August, 1978, Canada’s University of New Brunswick had planned to confer upon him an honorary Doctor of Science degree during a rare graduation ceremony that had been planned at the Kenya Technical Teachers College in Gigiri, Nairobi. It was the first honorary degree that Kenyatta was to accept from a foreign university.

The university had agreed to fly in its graduands to Nairobi, among them 28 Kenyans, since President Kenyatta could not fly to Canada. At first, the ceremony was set for June 1978 but was pushed to October 5, Ottawa Citizen had reported, quoting a Canadian High Commission official shortly after Kenyatta died.

As a tradition, university honorary degrees cannot be awarded in absentia. With the demise of Jomo, the university gave the honorary degree to President Moi during the Nairobi ceremony on March 16, 1979 ceremony, which also marked the official opening of the Canadian-funded KTTC, by then the largest aid project undertaken by the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA).

Moi's first honorary degree

This was also Moi’s first honorary degree having accepted and, strangely, declined an award by Indiana Central University in May 1977. Moi had asked the US Embassy in Nairobi to have the appropriate official in Washington DC write to the Indiana Central University President Dr Gene Sease “and inform him that vice-president deeply regrets the necessity of cancelling the visit... having accepted invitation and agreeing to receive honorary degree.”

A confidential note sent to the US Bureau of African Affairs by US Embassy said: “Moi would like this to be done discreetly and to avoid any publicity whatsoever. Moi requested specifically that degree not be awarded in absentia.”

Why Moi could not travel is, again, not known and he hardly mentions the reason in his book, but despite his plea, the story appeared in the university magazine that he had been awarded a Doctor of Law degree, but could not receive it.

It was his relationship with the Canadians that would cement the future of the education system that Kenya would have for several decades. Initially, the KTTC teachers were all Canadians before Kenyans trained in Canada, mostly at the University of New Brunswick, took over.

The man behind most of these efforts was Dr Colin Mackay, the President Emeritus of New Brunswick and an adviser to CIDA. Back at the university, he had resigned as president after the 1968 Strax Affair in which he was viewed as the “symbol of oppression to the University radicals” due to his “autocratic style” of leadership. That is according to his executive assistant, Peter Kent, the author of Inventing Academic Freedom: The 1968 Strax Affair at the University of New Brunswick.

To digress a bit, the Strax Affair involved the resistance that Dr Mackay faced after he attempted to introduce photo identity cards at the university and a protest led by a physics professor Norman Strax snowballed into a debate on academic freedom. Mackay had not only fired Dr Strax, but also sought a court injunction accusing him of being a ‘dangerous influence’ to the students.

It was after this that Dr Mackay resigned and started working with CIDA as an adviser. During his tenure, he was instrumental in the setting up of KTTC in Kenya and various other education projects in Africa. Then, the university created the position of President Emeritus; specifically for Dr Mackay.

In this file picture, former President Daniel Arap Moi lays the foundation stone on the proposed new classroom of Chepterwai Girls Secondary School.

Canadian model of education

It was during this period that President Moi approached Dr Mackay to look into the prospects of starting a second university in the country. During the KTTC graduation, Moi had announced that Nairobi and Mombasa polytechnics would be expanded and that a third national polytechnic would be built.

But rather than stick to the original mandate, Dr Mackay recommended the restructuring of the entire education system, putting emphasis on technical subjects and information science, hoping to end unemployment in the country. He also recommended the setting up of the second university in the Rift Valley, which was the main part of the terms of reference.

It was through Dr Mackay that Kenya adopted a Canadian model of education, the 8-4-4 system, but with an emphasis on vocational training. This came as a surprise to educationists – who would recall that in 1979, Moi had banned New Maths and ordered schools to revert to Traditional Maths.

Shortly after Mackay had handed over his report, President Moi had asked Prof Joseph Mungai, the vice-chancellor University of Nairobi, to draw up a report for implementing the programme.

“He came up with an excellent paper and we were all impressed with his suggestions. He recommended that the system be implemented slowly and carefully, one year at a time,” recalled Jeremiah Kiereini, who was then the chief secretary and Head of Civil Service, in his autobiography A Daunting Journey.

Moi had, then, created two Ministries of Education – Basic Education under Jonathan Ngeno, a bible college graduate and Higher Education under Kangema MP, Joseph Kamotho. Within the government, it was known that there would not be enough classrooms and the proposed workshops had not been built. More so, teachers had not been trained for the new syllabus. One afternoon, Moi announced that the 8-4-4 system would be implemented immediately.

“The system was implemented with ensuing bedlam, confusion and turmoil,” wrote Kiereini. “Perhaps Moi felt the need to assert his authority as President, and this was one of the avenues he chose.”

An alien system

Five years after the 8-4-4 system was put in place, Moi appointed the Presidential Working Party on Education and Manpower Training for the Next Decade and Beyond. Historian B.A. Ogot, the man who was its vice-chairman recalled in his autobiography that their appointment “was indicative of growing concern about the impact of the education sector on the entire economy and the need to carefully monitor it”.

Moi had realised that the 8-4-4 system could not be financed from the government coffers alone and one day, he asked the Prof Ogot group to make recommendations on cost-sharing. The interim report was handed in November 1986. When the team visited Canada, and Prof Ogot says as much in his book, My Footprints in the Sands of Time, Kenya had adopted “an alien system without its essential feature – the flexibility of options and timetabling which produced a wide choice of electives and credit promotion by subject rather than by year-long grade.”

It appears that there were many people in the Moi government who had expressed their fears about the 8-4-4 system – but not in public.

When Joseph Kamotho, the Higher Education minister by the time the 8-4-4 was launched, accused the Leader of Opposition, Mwai Kibaki, of criticising the education system after he was out of Moi government, Kibaki told him: “My view has been known since before the 8-4-4 system was introduced, that the children of nine, ten and 11 years could not bear the weight of that syllabus. It is not necessary for me to produce that evidence because if the minister for Education wanted to know, I can tell him where to refer.”

Years later, what was no doubt an experiment by a few people – ended up becoming the official system of education.

If the vice-president of Kenya had misgivings about it; and if the chief secretary and head of public service would describe it as being implemented in confusion and turmoil, then why were the children left to become guinea pigs in the experiment?

That is the question that nobody wants to answer.

[email protected] @johnkamau1