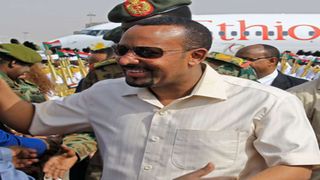

Ethiopia's Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed is welcomed at Khartoum International Airport on June 7, 2019.

| File | AFPAfrica

Premium

Abiy: Soldier-Spymaster stares at Ethiopian abyss

What you need to know:

- Abiy is driven by fear of losing recognition, fame and sense of worthiness, one of his closest aides once said.

- His mother is said to have prophetically predicted that he would become the “seventh king” of Ethiopia.

Even the most optimistic would have been reluctant to bank on a former soldier who set up a spy agency to oversee a transition from an authoritarian to a democratic government.

For such military types would be steeped in shadowy traditions and keen on secrecy and enforcing absolute compliance to decrees. The choice of Abiy Ahmed for Prime Minister of Ethiopia, however, sprung a surprise.

I was in Nairobi the morning the Norwegian Nobel Committee announced its pick for the Peace Prize 2019.

Colleagues attending a meeting in a closed boardroom whispered around the table before they showered me with congratulatory thumbs up.

Abiy Ahmed had just been recognised as a man who had done “much worthy of global recognition” since his ascent to political power in April 2018.

Indeed, it was a rare accolade none of his predecessors received. Abiy joined a list of seven Africans who were bestowed a peace prize, the most revered across the world, since Albert Luthuli, the first black African to have received the honour, in 1960.

I remember the headline in the New York Times edition the following day; ‘Abiy received the honour, but he had to earn it’.

For a man with a humble beginning in the small village of Beshaha, 414 km west of Addis Ababa, the Abiy phenomenon had captured the imagination of many in the world. Domestically, it rekindled hope and absolute optimism.

My colleagues who I met in Nairobi were among these, but more informed about the complexities of power politics in Ethiopia since its imperial days.

Abiy came of age at a time when the military regime that brought Imperial Ethiopia to an end was itself gasping for its last breath in early 1991. The students who had taken up arms nearly two decades earlier against the military junta were encircling Col.

Mengistu Hailemariam`s government, advancing to the west and south-west before the EPRDF army seized the capital, Addis Ababa, in May that year.

A month before, the ragtag rebel fighters had arrived in his village not too far from the town of Jimma, known as a source of the finest coffee variety.

Rebels advancing from the north often mobilised groups to join their march to Addis Ababa. The EPRDF was a coalition of four, including the OPDO, a rebel formation from prisoners of war captured by the TPLF and EPLF in Eritrea in earlier years.

Joined rebel army

Born to a Muslim father and a Christian mother in a predominantly Oromo community, Abiy was among the many who had dropped from school in his formative years to join the advancing rebel army.

Col. Hailemariam fled to Zimbabwe in May 1991, paving the way for the rebels under Meles Zenawi to capture the capital. A month later, a charter was adopted and Eritrea become a de facto State.

A transitional government was reconstituted. But it was not all-inclusive, which planted seeds of the enduring legacy of exclusion. Even those who had opted to join the EPRDF in the transitional government, such as the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF), were sidelined.

When Abiy rose to the pinnacle of power in April 2018, it was this legacy of political exclusion and economic marginalisation he was expected to address. A population exhausted by paralysis in leadership and infighting among the EPRDF leaders since the death of Zenawi in 2012 was dazzled by an animating address Abiy made before parliament.

It was not a familiar voice from a chamber of power when a newly elected leader asks for forgiveness for the cruelty and suffering the government he served in various capacities committed in the name of securing the State.

Many were mesmerised by his message of inclusiveness, forgiveness, freedom, accommodation and tolerance.

His declaration that his coming to office, following the resignation of his predecessor, Hailemariam Desalegn, was a “beginning of a new chapter” in the country`s history, thrilled many.

Abiy described his inaugural speech as a “social contract” he had entered with the Ethiopian people. He spoke, rather forcefully, about the importance of unity.

“Our unity is meshed not to untwine,” Abiy told legislators in the 35-minute address.

But Abiy also emphasized that unity should not be construed as “oneness”. He advocated rule of law, justice and rebuked state repression. He urged Ethiopians to embraced divergent views, describing it as “a blessing”. The attitude of “my way or the highway” cannot hold a country together, he declared.

He extolled constitutionalism and an environment where the state and those in power were held to account. He committed to fight corruption and wastefulness.

Willingness to end strife

He expressed willingness to end the bloody conflict with neighbouring Eritrea. Eritrea’s strongman, Issayas Afeworqi, responded in kind for the first time since the war broke out in the late 1990s.

Abiy was a junior officer in the army when Ethiopia and Eritrea went to war.

Ethiopian PM Abiy Ahmed welcomes Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki at the airport in Gondar on November 9, 2018.

Deployed as a radio operator attached to a platoon in the Bademe front, the flashpoint of the two-year border war, he had almost been killed in the frontline. His colleagues died when a shrapnel hit their tank.

A devout evangelical Christian, he religiously performs daily prayers.

He has always believed in his destiny as a leader of the countryis mother prophetically predicted him becoming the “seventh king” of Ethiopia.

He is on record claiming to have distanced himself from a romantic temptation with a French woman in Kigali, when he was serving under a UN peacekeeping mission there, for fear that it could derail his dream of becoming Ethiopia`s ruler.

Ethiopia's Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (right) is given an 18th century crown by Sirak Asfaw (lef), who had kept it hidden in his apartment in The Netherlands for two decades, during a hand over private ceremony in Addis Ababa.

Few were as close to him as Biniam Tewolde, a colonel in the federal spy agency. Abiy was instrumental in the formation of this agency, conceiving the idea while he was on training in South Africa in 2010.

Having risen to the rank of a mid-level army officer, he is credited for the blueprint that established the spy agency and securing the country`s information networks from foreign intrusion.

Biniam recalled the agency as a learning island. Its leaders, many of them in their prime age, were keen on attracting the best and brightest, fresh from colleges. Abiy was admired by the agency`s staff but did not stay long due to a feud with the founding director, a former rebel-cum-army general Teklebrehan Weldearegay.

Leaving the army after he was promoted to a Colonel, Abiy joined the political elite in the ruling coalition’s OPDO and was elected to its central committee in 2010. He ran for a seat in the federal parliament, representing a constituency in Gomma County, his birthplace.

It was during this time he pursued further studies and received his PhD from Addis Ababa University in 2017. Abiy studied the role of social capital in traditional conflicts’ resolution.

He looked into the causes of inter-religious conflicts in Jimma area, where religious tension had escalated in the late 2000s. For three years, he was a minister in charge of information technology, an area of interest during his undergraduate studies.

His re-election to parliament in 2015 was consequential. The ruling coalition was forced into soul-searching against the backdrop of widespread protests in the same year the EPRDF and its allies claimed 100 per cent control of all legislative bodies in the federal government and regional states.

The relentless demand for political inclusivity and economic equity by the youth, first in Oromia and subsequently the Amhara regional states, compelled the ruling party to pledge to change course. This included the change of its leadership, whose chairperson often is a prime minister.

Abiy was deputy to his once strong ally, Lemma Megerssa, in the OPDO. Megerssa’s absence from the federal parliament, however, meant he would not be elected as prime minister even if he became chairman of the EPRDF. The two swapped their places in the run-up to the EPRDF polls.

Abiy was overwhelmingly installed as EPRDF’s third chairman since its founding in the late 1980s. A month after, he was before parliament, making the most rousing speech ever made from that chamber. Abiy spoke about his mother and the mother of his three daughters. Through them, he acknowledged the contribution of women in building Ethiopia.

President Uhuru Kenyatta and Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed display Ethiopian traditional attire given to them by Gamo elders.

International praise

He got international acclaim. The BBC praised Abiy`s rise to power as the “leader promising to heal a nation”.

Healing the nation, Abiy tried, though. A few weeks in office, he implemented political and economic reforms. He released political prisoners, including Andargachew Tsegie and Eskinder Nega. He granted amnesty to insurgents and exiled oppositions figures.

He pushed changes to repressive laws and anti-terrorism law. Crucial institutions such as the judiciary, human rights and electoral bodies were reconstituted. Third-generation privatisation of state enterprises and liberalisation of the economy were set in motion. Even his political nemesis, Debretsion Gebremichael, chairperson of the TPLF, acknowledged his peace efforts.

These were measures the Nobel Committee applauded as giving “many citizens hope for a better life and a brighter future”.

Ethiopian PM Abiy Ahmed (right) receives the Nobel Peace Prize from Berit Reiss-Andersen, chairperson of the Norwegian Nobel Committee on December 10, 2019.

Close to a year later, Abiy`s Ethiopia is in a much murkier state than it may have ever been. Many wonder if Abiy has what it takes to ride out the storm. Often, he strikes those who worked with him as one with a singularly focused and determined mind. A man that is ultimately being helped by a higher hand in shaping the future of a country.

Abiy is driven by fear of losing recognition, fame and sense of worthiness, says Biniam, once his closest aide. And there are groups from the evangelical community, the private sector and the political elite nostalgic of Ethiopia`s past imperial glory who are happy to shower him with it.

Many, however, caution against underestimating Abiy`s capabilities. His ambition, love for grandeur and his boldness in betting against the odds have not failed him so far; after all, he is still the Prime Minister.

Abiy has a messianic allure about him that mobilises support from a wide array of groups in society. But he still seems to struggle to build a broader coalition. He may not be the philosopher king. But it is clear that he was onto something when releasing a book titled, Me`demer, an Amharic word, loosely translated to “positive sum-game”.

Abiy might have to juggle through the competing narratives of political forces predominantly in the integrationist or federalist camps if he is to secure a stable government, let alone a decent transition to a liberal democratic order.

He may see himself as standing above both, although his perceived closeness to the integrationist forces mostly serves as a manifestation of his ambition of grandeur. The stately the country he rules over, the bigger he may feel. But this camp could be a convenient ally, not an ideological one.

By publishing the book less than a year into office, and ensuring the completion of flashy projects in landmarks in the capital; he has shown his determination, dedication and discipline in delivering results.

No less overbearing is his sense of grandeur. A number of multibillion-dollar projects are standing symbols of his notion of state-building in the medieval-era style.