Premium

ICC to hold first hearing for Ugandan Joseph Kony

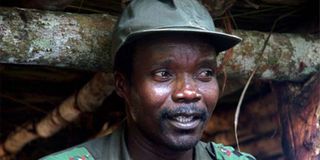

A file picture taken on November 12, 2006 of then leader of the Lord's Resistance Army Joseph Kony.

The International Criminal Court (ICC) is on Tuesday holding its first confirmation of charges hearing, in absentia, Joseph Kony, the elusive leader of Uganda’s much-diminished Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA).

The proceedings, nonetheless, will mark a milestone in the pursuit of justice for one of Africa’s most notorious warlords, who has evaded capture for 19 years since his indictment by the court.

Kony will be represented his legal team led by Counsel Peter Haynes and is suspected of 36 counts of war crimes and crimes against humanity allegedly committed between July 1, 2002 until December 31, 2005 in northern Uganda.

His case initially involved co-accused Raska Lukwiya, Okot Odhiambo and Vincent Otti, all of who have since died. The ICC normally discontinues cases against dead suspects.

LRA's Joseph Kony/REUTERS

Joseph Kony, now in his early 60s, founded and commanded the Lord's Resistance Army, a rebel group that has terrorised communities across East and Central Africa for more than three decades. A self-proclaimed spiritual medium from northern Uganda’s Acholi region, Kony claimed divine inspiration for his violent campaign against the Ugandan government and civilians alike.

He rose to prominence in 1987 when he formed the LRA from remnants of Alice Lakwena’s Holy Spirit Movement. What began as a religious rebellion soon evolved into one of the world’s most brutal insurgencies, marked by mass abductions, the forced recruitment of child soldiers, and systematic sexual violence.

The LRA initially presented itself as a movement to topple President Yoweri Museveni, but its ideology was vague, mixing Christianity, traditional Acholi beliefs, and Kony’s mysticism.

Under his command, the group became synonymous with brutality. More than 60,000 children are believed to have been abducted over two decades—forced into combat, domestic servitude, or sexual slavery. Nearly two million people in northern Uganda were displaced, many confined to government-protected camps where conditions were dire.

By 2005, the LRA had shifted operations outside Uganda, moving through the Democratic Republic of Congo, Central African Republic, and South Sudan. Today, the group is estimated to have just a few hundred fighters left, but its presence continues to destabilise the region.

The ICC case against Kony centers on murder, enslavement, sexual slavery, rape, forced pregnancy, torture, cruel treatment, and the use of children under 15 in armed conflict.

The leader of Uganda's Lord's Resistance Army rebels Joseph Kony (in white). Photo/REUTERS file

Prosecutors say Kony, as the LRA’s commander, bears responsibility for attacks on camps for internally displaced persons in Pajule, Odek, Abok, and Lukodi, where hundreds were killed and thousands abducted.

The abduction and use of child soldiers form one of the most shocking aspects of the case. Children as young as eight were kidnapped, subjected to violent initiation rituals, and forced into combat. Boys were made to kill—sometimes even their own relatives—while girls were taken as “wives” by commanders.

Kony’s whereabouts remain unknown, though intelligence reports suggest he hides in remote border areas between the Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of Congo, and South Sudan. Despite repeated international efforts, including African Union missions backed by US military advisors, he has evaded capture since 2005.

Analysts say the LRA is now a shadow of its former self, reduced from thousands of fighters to fewer than 300. But Kony’s continued freedom remains both a security threat and a symbol of impunity.

Today’s hearing is a first for the ICC, where proceedings go on without the accused being present. Pre-Trial Chamber III ruled that the requirements were met after determining Kony “cannot be found.”

While charges can be confirmed in absentia, ICC rules prohibit a full trial without the accused in custody. Judges will assess whether there is sufficient evidence to move the case forward, pending Kony’s arrest.

Kony is not the only LRA commander indicted by the ICC. Dominic Ongwen, another senior commander abducted as a child, surrendered in 2015 and faced 70 counts of war crimes and crimes against humanity. He was convicted in 2021 on 61 counts and sentenced to 25 years in prison.

Of the five LRA leaders originally indicted, Ongwen is the only one in custody. Kony remains a fugitive, while the others are dead or presumed dead.

Joseph Kony, leader of Uganda's Lord's Resistance Army.

Impact on Ugandans

For communities in northern Uganda, today’s hearing carries deep significance. The LRA insurgency killed an estimated 100,000 people and displaced millions. Survivors see the proceedings as a long-overdue step toward recognition of their suffering.

“This hearing gives voice to the voiceless,” said Grace Acan, a prominent survivor and advocate. “Even if Kony is not in the dock, the world will hear about our pain.”

But the absence of the accused has also raised concerns that justice may be more symbolic than substantive. Some in northern Uganda have turned to traditional reconciliation practices such as mato oput—a cultural ritual emphasizing forgiveness and community healing.

Today’s confirmation hearing will be closely watched by victims, Ugandan communities, international justice advocates, and African governments. While it cannot deliver a full trial without Kony present, it represents an unprecedented step by the ICC and a measure of recognition for survivors who have waited nearly two decades for accountability.

For now, Joseph Kony remains a fugitive somewhere in Central Africa. But today, his alleged crimes will finally face judicial scrutiny—even if he does not.