Premium

Idriss Deby, who stood by the gun, felled by bullet in battle

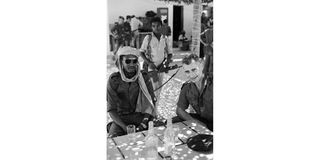

In this file photo taken on December 14, 2006, Chadian President Idriss Deby (C) inspects a seized rebel technical in Adre, Chad.

What you need to know:

- Deby’s rise was also a case of one outdoing their master. He has said in the past that he joined the army to protect his community at a time factions were fighting in the country.

When Idris Deby Itno was born 68 years ago, his herder family probably knew he would spend his life looking after sheep, the mainstay of his Zaghawa tribe.

But by the time he was announced killed in a battlefield on Tuesday, the President of Chad had become a unique figure. He remained one of the few African heads of state in modern times who were warriors for life, visiting the country’s military to take part in fights on the battlefield.

On Tuesday, as the Chadian army announced he had died of gunshot wounds, Deby had risen to a pilot, soldier, politician and strategist; all of which left behind a trail of defeated, even dead, rivals in his wake.

“He breathed his last while protecting the sovereign nation on the battlefield,” said Army Spokesman Azem Agouna in a briefing on the State television. The injuries were sustained on Sunday, Gen Agouna said, after Deby visited his troops as they fought rebel groups who had attacked from neighbouring Libya.

Mousa Faki, a Chadian diplomat who heads the African Union Commission, had said on Tuesday morning that the foreign fighters had challenged the constitutional order in the country.

“The Chairperson of the Commission strongly condemns these acts of aggression, which constitute an unacceptable attack on the constitutional order and stability of the Republic of Chad, at a time when the country has just organised regular and peaceful presidential elections,” Faki, a former Foreign Minister in Deby’s government said.

“The Chairperson of the Commission reiterates the AU's unwavering commitment to peaceful solutions to African problems through dialogue and consensus building."

In this file photo taken on September 26, 1983 French General Jean Poli (D), chief of French military operation Manta, poses with Chad's Chief of Staff Idriss Deby as part of French intervention assisting Chad's army against Lybian Forces.

300 rebels killed

The army said it had killed 300 of those rebels under the name of Front for Change and Concord in Chad (FACT). They killed 36 soldiers, however.

The army said a military council led by the late president’s 37-year-old son Mahamat Idriss Deby Kaka would run the country for 18 months during which the constitution will be suspended.

As a politician, Deby grew from a mere military commander who seized power from his erstwhile boss Hissène Habré in 1990, to maneuvering his way to stay in power longer. In 2016, Habré, who had fled the country to Senegal, was sentenced to life in prison by a Dakar Court for violations of his time while in power.

Deby amended the Constitution for a third time in 2018, expanding his powers by eliminating a Prime Minister who usually headed the government and transferring those powers to the President. Five-year presidential terms were turned to six-year terms, but Presidents were limited to two terms. However, as the law could only apply to future events, it meant Deby who was by then in his fifth term could continue to contest, and win, until 2033. On Monday, the country had announced him winner of April 11 elections, scoring 79.3 percent of the vote.

Yet Deby was popular mostly by crushing the dissent. In this election, the Human Rights Watch said Deby had targeted his opponents, forcing most to quit.

In one attack on February 28, security forces raided the home of opposition leader and presidential candidate Yaya Dillo and killed his 80-year-old mother and injured several other family members. Officials claimed Dillo had resisted arrest and fought back.

“As many Chadians are bravely taking to the streets to peacefully call for change and respect of their basic rights, Chad’s authorities have responded by crushing dissent and hope of a fair or credible election,” said Ida Sawyer, deputy Africa director at Human Rights Watch.

In this file photo taken on April 2, 1984 in N'Djamena, French General Jean Poli (R) meets Chad's Chief of Staff Idriss Deby after a terrorist attack provoking an airplane explosion.

Deby’s presidency, though, was one of looking over his shoulder. He faced coup attempts, rebellions, armed terror groups and corruption. He responded by crushing critics. In 2005, after removing term limits from the constitution, Deby ran an election largely boycotted by opponents the following year. Instead, he won by a landslide and celebrated that by adopting the name Itno from his local ethnic group.

He had won the first multiparty election in 1996 (having been interim leader since taking over in a coup in 1990). Yet those polls were also marred with irregularities. Subsequent polls in 2001 and 2006 polls followed the same pattern.

Trusted lieutenant

Deby’s rise was also a case of one outdoing their master. He has said in the past that he joined the army to protect his community at a time factions were fighting in the country. But he became one of Habré’s trusted lieutenants, helping him secure power in a 1982 coup. Their relationship, however, started to strain towards the end of 1980s when he was accused of plotting to depose Habré.

Deby would escape to neighbouring Darfur in Sudan, from where he launched an offensive on the capital N’Djamena. By the time his troops arrived in the capital, however, Habré had fled, leaving behind a trail of crimes against humanity. Deby followed that by forming a new government after suspending the constitution.

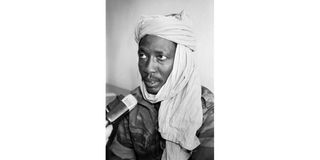

In this file photo taken on December 2, 1990 Chadian rebel Idriss Deby, leader of the Chadian Patriotic Salvation Movement, gives a press conference, on december 2, 1990 as he arrives in N'Djamena.

Deby ran a country of poor people, despite its rich resources, producing some 100,000 barrels of oil per day. In 2006, he controversially expelled oil giants Chevron and Petronas for refusing to pay some $450 million worth of taxes. US oil firm Exxon took over the pipeline consortium of about 1000km through Cameroon.

Critics, though, argued that he had expelled the two to create room for Chinese oil merchants, after the country re-established diplomatic ties. Deby would, 10 years later, levy $74 billion worth of royalties on Exxon. Exxon paid the money, which was 700 percent of the Chadian economy.

Yet, despite his misgivings, Deby’s longevity in power became useful to the region as it fought concerted war against terror group Boko Haram. Spread across Nigeria, Cameroon and neighbouring Sahel regions, Boko Haram and other militant groups forced the countries to unite on the military front, supported by the EU and the US.

The African Union did not immediately indicate its position on the Tuesday move to suspend the constitution. But the next 18 months could determine whether the country weathers attacks from FACT, which is based in Libya.