Renewable energy: The magnet shaping China’s quest for Africa

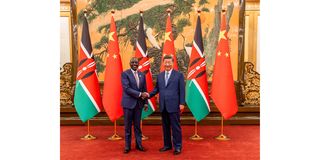

President William Ruto meets his China counterpart Xi Jinping at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, China.

What you need to know:

- China is investing in the first mega-scale battery factory on the continent, in Morocco.

- Chinese interests also have permission to develop the world’s largest untapped high-grade iron ore deposit, in Guinea.

China-Africa relations have deepened over the past two decades, characterised by increased economic cooperation, investment and infrastructure development. China is now Africa’s largest trading partner, with partnerships focused on building roads, railways and energy projects.

As the ninth Forum on China–Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) kicks off this week in Beijing, a new, green theme is shaping their relationship: the global renewable energy race.

We asked Lauren Johnston, a development economist with expertise in China-Africa relations, to provide some insights into this development as it positions both regions as key players in the global shift towards green energy.

How is the race for green energy shaping relations between China and Africa?

The global climate crisis has created a push for renewable energy technology – like solar or wind power – which would lessen reliance on polluting energy sources. China saw some years ago it had a chance to lead in such a new industry.

Africa is home to a lot of the important minerals needed to create renewable technologies – like copper, cobalt and lithium, key ingredients in battery manufacture.

The race for green energy is therefore leading to a rush for these minerals in Africa, led by China, the US and Europe.

Chinese mining presence in Africa, which is much lower than western presence, is concentrated in five countries: Guinea, Zambia, South Africa, Zimbabwe, and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

Among them, the DRC, Zambia and Zimbabwe are the crucible of the new green energy race in Africa. They are home to Africa’s copper belt and the greatest store of lithium, copper and cobalt.

The DRC is particularly important. It has significant reserves of cobalt and high grade copper, as well as lithium. Cobalt is an unusually hard metal with a high melting point and magnetic properties. It is a key ingredient in lithium batteries.

More than 70% of the world’s cobalt is produced in the DRC and 15%-30% of that is produced by artisanal (informal) and small-scale mining.

China is the leading foreign investor – it owns some 72% of the DRC’s active cobalt and copper mines, including the Tenke Fungurume Mine – the world’s fifth largest copper mine and the world’s second largest cobalt mine.

China’s CMOC Group is the world’s leading cobalt mining company. It could produce up to 70,000 tonnes, thanks to the new Kisanfu mine.

In 2019, the DRC and China were responsible for about 70% of global production of cobalt and 60% of rare earths.

Zimbabwe is another country in which China has been investing within the context of the green energy race. Zimbabwe is home to Africa’s largest lithium reserves, a critical element in electric-vehicle battery production. In 2023 Prospect Lithium Zimbabwe, a subsidiary of Chinese company Zhejiang Huayou Cobalt, opened a US$300 million lithium processing plant. It has capacity to process 4.5 million tonnes a year of hard rock lithium into concentrate for export, against a global backdrop of some 200 million tonnes produced annually.

Zimbabwean president Emmerson Mnangagwa (L) shakes hands with a representative from China’s Sinomine Resource Group at Bikita Lithium Mine (2023). Tafara Mugwara/Xinhua via Getty Images

There are a couple of other developments on the continent that are worth watching.

China is investing in the first mega-scale battery factory on the continent, in Morocco.

Chinese interests also have permission to develop the world’s largest untapped high-grade iron ore deposit, in Guinea. Iron ore, used in steel production, plays a crucial part in the renewable energy sector in several ways – for instance, steel is used in wind turbines and in mounting structures for solar panels. The agreement to exploit the Simandou iron ore deposit involves various countries. China’s steel-making giant Chinalco is among the players. Production is due to begin in early 2026.

As China ramps up investments in these green minerals, what concerns exist for African countries?

China’s growing control over key renewables minerals brings several challenges to African minerals suppliers.

For African countries it generates concerns for development – many want to add value to their minerals endowment at home rather than export raw materials to China and then import manufactures. China has been criticised for abandoning African interests by adding value in China and not in Africa. Many people and industries on the African continent lack access to reliable and affordable energy – and local industry is keen to capture that market.

For instance, according to the International Energy Agency, China controls over 80% of the global manufacturing steps involved in making solar panels. The concentration of production in China, alongside competition, has pushed down global solar panel prices.

China’s solar industry is keen to close Africa’s energy gap, providing sustainable energy to the millions that don’t have access. For instance, at this year’s Forum on China–Africa Cooperation gathering, China is expected to advance its Africa Solar Belt Programme. This is an agenda supported by the World Resources Institute which not only seeks to use solar energy to close Africa’s energy gap, but also to focus on powering schools and healthcare facilities with solar too.

Some countries, like South Africa, are pushing back by imposing tariffs on solar imports to protect their local industries.

There are also fears that the race to renewables, and the approach of Chinese mining-sector firms in Africa, is setting back workers’ conditions. Expansion of mines in some countries has also led to forced evictions and human rights abuses.

What can African countries do differently to take advantage of China’s mineral rush?

There are several steps they can take.

First, they can pay more attention to basic labour standards and human rights.

Second, African firms should aim to learn from their Chinese partners. They can develop the industrial knowledge and understanding of the skills and capabilities needed on the continent, similar to how China learned from Japanese, Taiwanese, Singaporean and western companies in the past.

Third, learn from how other emerging markets manage their relations with China. For instance, with China’s help, Indonesia has taken control of the global nickel market. Indonesia started by banning nickel exports in 2014, aiming to build up its own industries for processing and manufacturing. This plan was supported by Chinese investments.

Lastly, what I call China’s Hunan Model for Africa has a focus on agriculture, mining, transport and construction industries, and on building talent. This includes technical and vocational training.

The more African nations position themselves to take advantage of training programmes from other countries, the better their young people will be prepared to drive industrial growth and economic development in Africa.

Written by Lauren Johnston, Associate Professor, China Studies Centre, University of Sydney