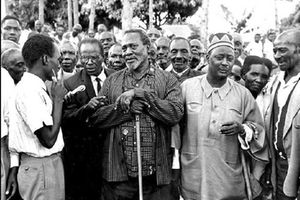

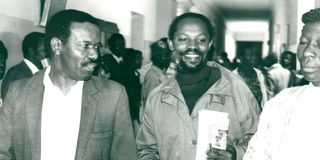

‘Society’ Managing Editor Blamuel Njururi (left), ‘Society’ Editor Pius Nyamora (centre), and his wife Loyce in a Mombasa court on April 24, 1992. Nyamora, his wife and three of the magazine’s writers had been remanded on 11 counts of sedition.

In an era awash with journalistic retreat, Blamuel Njururi stood apart — unflinching, unsparing, and defiantly unbought. He was instantly recognisable: a man of quiet intensity, often seen driving his Citroen through Nairobi’s restless streets, a leather briefcase always by his side.

For more than five decades, he wielded his pen not for profit or praise, but as a weapon against impunity, injustice, and silence. Even in retirement, Njururi refused to fade into comfort. He remained a vigilant citizen — filing petitions to Parliament, challenging powerful figures, and pressing for reform in his own principled, persistent way. Speaking truth to power was not a phase for him; it was a lifelong calling.

In the turbulent 1990s — an era marked by political repression, economic anxiety, and the battle for multiparty democracy —Blamuel Njururi emerged as a formidable force in the realm of independent publishing.

At a time when the State tightened its grip on media houses and many editors hedged their truths, Njururi chose the harder path: to speak boldly, to publish defiantly, and to remain unbought. His name became synonymous with investigative grit and editorial courage often cited along Gitobu Imanyara, Pius Nyamora, and Njehu Gatabaki.

Through publications such as Society and later Kenya Confidential, he carved out spaces for alternative narratives that challenged the official line and amplified the voices of dissent.

Those who knew him — fellow journalists, human rights activists, and even those he held to account — agree on one truth: that Kenya is a freer, more conscious, and more democratically awakened nation because Blamuel Njururi, among others, chose to write.

He wrote fearlessly, relentlessly, and with unshakable principle — refusing to be silenced, no matter the cost. His was not just journalism; it was a moral undertaking. And through it, he helped redraw the boundaries of press freedom in Kenya, though critics dismissed such journalism as ‘Gutter Press” or “Yellow Journalism.”

Njururi, who was born in 1948 and passed away on Tuesday June 17, 2025, was more than a journalist. He was a truth-teller who walked though the turbulence of Kenya’s post-independent politics.

Educated at Kangaru School in Embu and later at the University of Nairobi — where he earned his Bachelor of Arts and a postgraduate diploma in journalism — he emerged not merely as a reporter, but as a crusader.

From his early posting as an Information Officer in 1968 to the heights of editorial power at Nation, East African Standard, Kenya Times, Weekly Review, and Society, Njururi stood at the intersection of journalism and resistance. His pen was his protest and the newsroom was more of a platform for democratic change.

Those who worked with him at the Old Nation House, along Tom Mboya Street, say that Njururi was not just a newsroom presence — he was a force. In an era when many journalists capitulated to the iron grip of the Jomo Kenyatta and Daniel arap Moi excesses, Njururi dared to speak truth to power. He wielded the written word like a scalpel, excising the cancers of bad governance, corruption, and authoritarianism from Kenya's public discourse.

In the shadow of repression, he flourished as one of the country’s foremost investigative editors — exposing financial scandals, political betrayals, and state-sponsored violence. While at the Nairobi Times — the precursor to the now-defunct Kenya Times —Njururi distinguished himself as a dogged investigative reporter, unafraid to expose the nexus between politics and profiteering.

It was there that he broke the explosive Ken-Ren Fertiliser scandal, uncovering how powerful political interests deliberately sabotaged the construction of a fertiliser factory in order to continue profiting from lucrative import deals. His reporting laid bare a pattern of economic sabotage cloaked in policy—a tale of greed disguised as governance.

Later, during his tenure at Economic Review, Njururi cemented his role as one of Kenya’s most fearless watchdogs. He became part of the pioneering investigative team that relentlessly pursued the Goldenberg scandal — one of the country’s most notorious economic frauds.

Long after others moved on, Njururi and his colleagues kept digging, connecting dots, exposing shell companies, and tracing the multi-billion-shilling web of deception that implicated the highest offices in the land. Alongside Goldenberg, he also tracked other murky deals of the Moi era, each report a testament to his commitment to journalistic vigilance and public accountability.

Njururi was a veteran of the Old Nation House on Tom Mboya Street, a battleground of editorial integrity in the 1970s and 1980s. There, and later across many newsrooms, he trained generations of young reporters, instilling in them a deep respect for truth, design discipline, and investigative rigour.

A holder of multiple “Kenya Journalist of the Year” awards — Nation Group in 1975 and Nairobi Times (Stellascope Group) in 1978 —his editorial excellence was matched only by his editorial courage.

As East African Bureau Chief for Inter Press Service (1979–1981), and later as Foreign Editor at Standard Group, he covered historic events like the Commonwealth Heads of State and Government summit in Melbourne, Australia, with grace and gravitas.

In the murky and often treacherous waters of Kenya’s Second Liberation, Njururi was not a mere chronicler, but a combatant. He was one of the few prominent journalists who refused to be cowed or compromised, and stood at the frontline of a press war against state censorship and political repression.

As Managing Editor of Society magazine, he oversaw a string of hard-hitting stories that the State deemed incendiary. The backlash was swift and severe.

In 1992, following the magazine’s publication of sensitive documents allegedly linked to the assassination of Foreign Minister Dr Robert Ouko, the government unleashed its machinery of intimidation.

The magazine’s publisher, Pius Nyamora, along with writers Mwenda Njoka, Mukalo wa Kwayera, and Laban Gitau, were slapped with trumped-up sedition charges and dragged before courts strategically located far from Nairobi — part of a deliberate strategy to exhaust them and muzzle dissent.

When his colleagues were arrested, Njururi didn’t flee; he went underground, relocating operations away from Tumaini House to avoid detection. In a daring act of defiance, he produced the next issue of Society in secrecy — determined that the magazine would not be silenced.

But as presses kept rolling, the State tightened its grip. The police raided Fotoform Printers and seized all 10,000 copies of the issue in a dramatic show of force meant to cripple the publication.

Njururi was eventually captured and charged separately, becoming ensnared in a politically motivated judicial vendetta that would stretch on for 14 months until then-Attorney General Amos Wako finally dropped the charges in 1993.

This episode did not just define Njururi’s courage; it underscored the existential risk of telling the truth in an era when journalism was an act of civil resistance. But he was not done. If the mainstream media would not carry the voice of a rising, restless opposition, then Njururi would create a platform that did.

In 1997, he launched Kenya Confidential—a defiant, hard-hitting alternative weekly newspaper committed to covering what the gagged press ignored. Kenya Confidential, which mirrored Africa Confidential, stood as a bulwark against censorship and a torchbearer of multi-party ideals. His earlier ventures like Nairobi Weekly Observer had been crushed by state machinery, but Njururi persisted.

In December 2004, as editor and publisher of Kenya Confidential, he was again detained by police—this time on the eve of his daughter’s wedding. Only the personal intervention of CID boss Joseph Kamau secured his temporary release.

But he was not only a journalist of the past. In 2016, well into his seventh decade, he petitioned Parliament to amend the National Transport and Safety Authority Act. He called for a National Road Safety Insurance Fund to shield victims of Kenya’s devastating road carnage — a testament to his enduring concern for ordinary Kenyans. He also raised various corruption allegations against powerful individuals.

On his Facebook banner, Blamuel Njururi had a simple creed: "Corruption is Evil." It was not just a slogan. It was a life mission.

In his heydays, he was a man who drove a Citroen through Nairobi’s turbulent decades, carrying nothing but a briefcase and an unbreakable belief in the power of truth.

To those who knew him, Njururi was principled, warm, and endlessly tenacious. To his readers, he was a beacon of clarity and resistance. To corrupt officials and power-hungry elites, he was a persistent thorn in the side—unyielding, unafraid.

Blamuel Njururi belonged to a vanishing breed — the kind of journalist who not only reported history, but helped shape it. A warrior for a free press. A freedom fighter in the truest sense. A teacher to generations. A provocateur of conscience. A patriot without compromise. He leaves behind a nation freer, more awake, and more accountable because of his labours.

[email protected]; on X: @johnkamau1