An intersex person follows proceedings at Kenya National Commission on Human Rights offices in Nairobi on July 9,2018 during the launch of nationwide data collection on intersex persons in Kenya.

| Evans Habil | Nation Media GroupNews

Premium

It’s a dog’s life for Kenya’s intersex community

What you need to know:

- A look at an intersex person cannot reveal whether they are a man or woman; many of them exhibit characteristics associated with both sexes.

- For the first time in Kenya’s history, the intersex persons participated in the 2019 Census and a total of 1,524 were recorded.

In many traditional African communities, a woman who gave birth to a baby with any deformities or disability was rejected by her family and the child considered to be a bad omen to the larger society.

Women who gave birth to intersex babies were also subjected to the same fate, besides being divorced by their husbands.

A quick look at an intersex person cannot reveal whether they are a man or woman, since many of them exhibit characteristics associated with both sexes.

Thus, despite having female reproductive organs, many have opted to live like men – sporting men’s trousers, vests, shirts/t-shirts and shoes.

A report by the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights (KNCHR), the Secretariat of the Taskforce on Policy, Legal, Institutional and Administrative Reforms regarding Intersex Persons in Kenya established that intersex persons are a marginalised, minority and vulnerable group.

The study further noted that this group continues to face a multitude of challenges and human rights violations from birth, including stigmatisation, ridicule and discrimination.

The task force was constituted in 2017 by the Attorney-General.

The report decried general lack of awareness about the intersex condition and the appropriate ways of supporting an intersex child and the immediate family.

The key areas affected include registration of persons, health, education, employment, civil registration, social protection, immigration and access to justice.

The third gender

The report further brought to light limitations to enjoyment of their basic rights, such as use of mobile money, bank services, insurance policies, access to education and employment.

Recently, the commission embarked on an awareness and sensitisation campaign in the Coast region on the third gender.

For the first time in Kenya’s history, the intersex persons participated in the 2019 Census and a total of 1,524 were recorded.

However, according to Kwamboka Kibagendi, an intersex person with ‘JINSIANGU’, a community-based organisation, the number is higher across the country, but intersex persons are not coming out due to stigma.

JINSIANGU, whose mission is to create a safe space for the Intersex, Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming (ITGNC) individuals, called upon the Senate to hasten amendment of the Constitution to recognise intersex persons.

While the Constitution recognises and protects intersex persons’ human rights, there are serious gaps in legal, institutional and administrative processes, which fail to take cognisance of the existence, needs and challenges of intersex persons.

The envisaged amendments will affect the Person Deprived of Liberty Act,2014, the Children Act,2001, the Birth and Death Registration Act, the Registration of Persons Act and the Kenya Citizenship and Immigration Act.

Kibagendi said public awareness would help change people’s attitudes towards intersex persons and encourage more to come out and fight for recognition by both the national and county governments.

“It is a challenge for the few intersex persons who have come out to speak about their plight since the community does not believe us and, in most cases, they feel we are faking everything,” says Kibagendi.

Seeking recognition

Kibagendi says these challenges affected the 2019 Census, which saw few intersex persons come out. Parents, too, failed to reveal that they had intersex children.

The enumerators were also not informed about the gender, so they did not ask if one was intersex.

“We want recognition, we also want to share information on intersex so that 10 years from now we will have thousands of intersex persons living happily and enjoying equal rights, just like any other gender,” says Ms Kibagendi.

Kibagendi called upon the county governments to offer health services to intersex persons without discrimination.

“Most families with intersex children come from poor backgrounds and cannot afford to take their children to hospitals in Nairobi due to the high costs,” says Kibagendi.

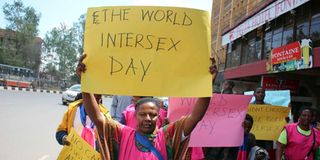

Intersex persons march on the streets in Nairobi to present a petition to Parliament on October 26, 2016. They were also celebrating the International Intersex Awareness day.

The August 2019 Census indicated Kilifi County had the highest number of intersex persons (25), followed by Kwale County (18). Taita-Taveta had seven, Lamu (4) and Tana River County (2).

Fiddie Omolo, an intersex focal person from Malindi sub-county, said most were yet to come out due to fear.

“Currently, there are about 42 intersex persons in Kilifi and many others are still hiding due to the many challenges we are facing. Even parents are not willing to disclose their children’s intersex status for fear of rejection,” says Omolo.

“I was arrested and found myself at Shimo la Tewa GK Prison. I explained my status and was given a separate room, but what followed was quite inhumane. The person who was serving food came and placed it behind the door and left,” says Omolo.

Subjected to humiliation

Though Omolo had not been imprisoned, he was denied freedom and subjected to humiliation by senior officers.

“It reached a point where a senior officer wanted to befriend me only because he wanted to spy on my genital organs,” says Omolo.

Omolo called upon the government to sensitise prison officers about the intersex gender.

“Prison officers should understand that we are human beings who also have rights and being Intersex is not by choice. It is not an easy task and I am alive today because my mother had to take her own life in order to save me,” adds Omolo.

Omolo appeals to parents and intersex persons to speak openly about their status in order to get support.

The activist added that it has become difficult for intersex persons from the Muslim community to come out in public despite their high numbers.

Sharon Ngeru from Kiambu was born a girl but lives like a man.

“It is tough for me because it is difficult for the community, starting from my home, to get to know and understand me. They think I pretend to be someone different, not male or female. Some say I am a Lesbian,” says Ngeru.

The first-born in their family, Ngeru went to a primary school in the locality and was thereafter taken to a girls’ boarding school after sitting for her Kenya Certificate of Primary Education (KCPE) examinations.

Exhibited male characteristics

“It was difficult for me because I knew I was not female. I have never received my monthly periods and can’t explain what menses are. I do not even know how to use sanitary towels,” says Ngeru.

To bear the strict rules that required all the girls to report back with sanitary towels, Ngeru started absenting herself from school during the first weeks for fear of being harassed by the boarding teacher.

“While inspecting my box, the teacher would wonder why I had not carried sanitary towels and I lacked words to explain,” says Ngeru.

Due to her condition, Ngeru would wake up as early as 4am to shower in order to avoid being exposed.

“The girls had many questions about me and how I used to behave. Some wanted me for a girl-to-girl relationship, just to find out what I had,” adds Ngeru.

At school, Ngeru exhibited male characteristics, complete with a fast-growing beard.

“The beard was bushy, forcing me to shave it with a razor blade all the time in order to look like a girl,” Ngeru explained.

Discrimination saw Ngeru feigning sickness to be away from school. So attracted to girls was Ngeru, to the point of going to peep into the bathroom as they were taking a shower.

“I scored a D- in my Kenya Certificate of Secondary Education examination. I could have done much better but the school environment was not conducive for me,” Ngeru says.

Beaten by crowds

“Last year I secured a job and after three days I was attacked and stripped naked by a crowd and my fellow workers, who wanted to know my status,” Ngeru adds.

Even social amenities are a problem.

“I cannot use a public toilet because I can’t go to the gents yet I look like a woman. I also can’t go to the ladies’ as they would think I am a man. I have on several occasions been beaten by crowds who thought I was a thief,” Ngeru adds.

Gloria Luhanga was mistakenly arrested alongside drunk passengers in a vehicle in Machakos County.

“A lady claimed I was among them and I was arrested and taken to the police station. The officers could not tell whether I was a man or woman, until the Deputy OCS ordered that I be searched.

Intersex persons during a march at Nairobi streets to present a petition to parliament on October 26, 2016. They were also celebrating the International Intersex Awareness day.

They took me to a toilet but I refused to undress. The police officers could not even explain to their boss who I was. They told him that I had small breasts,” says Luhanga.

Luhanga was not booked in any cells, but was left to spend the night at the inquiry office.

“The officers and the deputy OCS left me stranded at the inquiry office. The team that came for the night shift thought I was a new police officer who had just been deployed at the station,” says Luhanga, adding that she was released the following day by the OCS after coughing up Sh1,000.

Self-discovery journey

The journey to self-discovery was tortuous.

“I was in Class Eight when I started asking my parents to tell me who I was, since I all along had been presenting myself as a lady, wearing dresses and girls’ school uniform. My parents could not give me an answer,” says Luhanga.

Somewhere between 12 years and 13 years of age, Sydney Etemesi started experiencing body changes.

“My parents disowned me and I recently came to know that they did that because society perceived me as a bad omen. My parents were even accused of practising witchcraft,” Etemesi says.

Etemesi moved from their rural home in western Kenya to Nairobi after sitting KCPE exams and resorted to heavy drinking and drug abuse, a habit that occasioned numerous run-ins with the police.

“I was stressed and my only saviour was alcohol. I’d be arrested in nightclubs and accused of being lesbian or gay,” says Etemesi.

“I could not speak much to defend myself as the police would lock me up in either the male of female cells, depending on my appearance at the time of arrest,” adds Etemesi.

It was challenging for Etemesi to use the washrooms in the men’s cells.

“I was comfortable in the female cells because it was hard for them to realise I am intersex.”

Despite the challenges, Etemesi is married and has a child.

Embarrassment and confusion

Though living as a man, Etemesi had monthly periods for six consecutive months after a period of three years.

“My periods are always painful and I have severe crumps. I also experience heavy flows in the first days,” says Etemesi.

In its report, KNCHR’s Secretariat of the Taskforce on Policy, Legal, Institutional and Administrative Reforms explains that a majority of the intersex persons of school-going age experience low levels of access to education, with only about 10 per cent of them attaining tertiary education.

Most intersex persons and their families go through shock, anger, embarrassment and confusion before ultimately accepting the intersex status.

About five per cent recognised themselves as intersex, while the others are mostly confused about their exact status.

The study also found out that a majority of intersex persons lacked birth certificates and, for those who had them, there was often a conflict between the recorded sex and the self-recognised sex.

Birth certificates make it difficult for intersex persons to acquire identity cards, a fact compounded by their physical appearance, which often clashes with the recorded sex.

And 54 per cent of intersex persons cannot access quality healthcare services due to high cost of treatment and inadequacy of specialised hospitals.

Parents and caregivers who had their children undergo corrective surgeries recorded mixed reactions.