Premium

Former detective reveals details of how outspoken Bishop Muge met his death

File I NATION

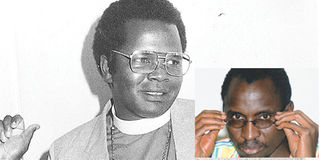

Bishop Alexander Kipsang Muge, the cleric who died in a tragic road accident many, including former intelligence officer James Khwatenge (inset), suspected was planned.

What you need to know:

- He talks of two previous plans by the dreaded Special Branch to ‘finish’ the vocal cleric

Had the Kiplagat team, which is supposed to dig out the truth from Kenya’s past, started off on the right footing, Kenyans would already have been treated to shocking details about their political past.

And it might just happen if they take up testimony from a former intelligence officer, James Lando Khwatenge, who has stepped out, saying the time has come to speak out on the atrocities committed in the 1980s and early 1990s by agents of the now defunct Directorate of State Intelligence.

The dreaded torture machine for the Moi government was commonly referred to as the Special Branch and Mr Khwatenge, who worked with the agency, says he knows the chilling details only too well.

He has contacted the Truth Justice and Reconciliation Commission to give his side of the story and provide highlights of what might turn out to be controversial revelations.

Mr Khatwenge, who left the security service as inspector in 1992, is waiting for his chance at the witness stand to tell Kenyans what he knows about the operations of the defunct State agency and the men and women they marked for torture and death.

Their only crime was challenging the government at a time when dissent was suicidal.

Anglican bishop Alexander Kipsang Muge was one of the many marked men. One of the Kanu hawks who had issued threats against the bishop was then Cabinet minister Peter Okondo. He had warned the bishop that should he step into Busia, he would not leave alive.

But Bishop Muge was not a man to take such threats. He was committed to the justice he lived and died for and he believed in speaking the truth.

On August 14, 1990 he decided to go to Busia for a crusade. On his way back to his Eldoret base, the outspoken cleric died in a mysterious road accident.

Observers and commentators did not miss the point of the threats that had been issued before his death. But that was as far as they could go.

Bishop Muge’s death was attributed to an ordinary accident. The driver of the “killer vehicle” was jailed for dangerous driving but died after serving five of his seven-year sentence.

Ordinary accident

But now Mr Khwatenge, who worked in Eldoret at the time, says the theory of an ordinary accident was only a cover-up, or even “an accidental” cover by the government for a murder well-planned and executed by agents of the Intelligence service. And that’s the testimony he so badly wants to tell the Kiplagat commission.

“This was an induced accident,” the former policeman told the Sunday Nation.

Mr Khwatenge says he was not involved in the mission and obtained details of what befell the bishop through his position in the Eldoret office.

According to him, days before the bishop died, four Special Branch officers from Nairobi arrived in Eldoret with specific orders to “finish the bishop” who was becoming a thorn in the flesh for the Moi regime.

This was at the height of clamour for the opening of democratic space and introduction of multiparty democracy.

Bishop Muge, Rev Dr Timothy Njoya and Bishop Henry Okullu were at the forefront pushing for reforms, but President Moi and his political lieutenants resisted, often accusing pro-reform voices of plots to destabilise the government.

The officers were seconded after “the Eldoret team failed to execute the mission”. At the time, Mr Khwatenge was serving in Eldoret as an inspector on a recent transfer from Mandera.

Bishop Muge’s biggest crime, claims the former security agent, was to publicly claim that people in West Pokot were dying of hunger and accusing the government of neglecting them.

“Those were the days when you could be poisoned but you could not say so. Everybody waited for our political leaders to say something then you all supported it. I don’t know for sure whether people were dying but I know that a decision was made to kill Muge,” Mr Khwatenge said.

Initially, two sites had been identified for the mission, he said. But each was dismissed for reasons that was not given to the assigned officers.

The first site was a ravine at Mutembur between Nasoko Girls High School and Kacheliba, West Pokot.

“The plot was to kill him and push his vehicle into the ravine and then fake an accident,” said Mr Khwatenge.

The second site was Chepkararat, inside Uganda but near the border with Kenya. Having worked in West Pokot, Mr Khwatenge remembers that the place was known for smuggling, prostitution and criminal activities.

Many people knew Bishop Muge in spectacles and simple hairstyle. In their plan, said Mr Khwatenge, Special Branch agents would remove his glasses and shave him clean. They would then remove his priestly robes and dress him up like a Pokot so that people would not recognise him. They would then take him and leave him among the tribal villagers who would have killed anybody dressed like a Pokot because of the enmity between the two cattle rustling communities.

Frustrating bishop

The plan to fake a disappearance was supposed to have worked perfectly well. This plan did not work and both police and Special Branch resorted to frustrating the bishop, he said.

A trained paramilitary explosives expert himself, those trailing him thought Bishop Muge somehow understood their motives.

“There are occasions he would be stopped on the road and be harassed. Whenever they did that, he recorded them on a voice recorder that he always carried in his pocket and kept the tapes,” said Mr Khwatenge. “It reached a stage when they were being pushed but they were not acting because he (bishop) was cleverer than them. He was a GSU-trained man, remember.”

Just when the Special Branch agents were considering giving up, an opportunity presented itself. The then Labour minister, Peter Okondo, warned him not to set foot in Busia.

“When Mr Okondo talked, he wanted to be seen to be so loyal to the President. As far as we in the Intelligence knew, he was not part of any scheme (to harm the bishop). Muge knew his life was in danger but when he heard Okondo saying that, it confirmed his fears so he dared them and went there.”

The minister was going to be the scapegoat, it was widely agreed. Immediately, four officers were dispatched from Nairobi to Eldoret. The four met a widely-feared senior officer. Mr Khwatenge recalls that the four men introduced themselves as dog handlers and requested an escort who would show them the crime-prone areas.

“They needed dog escort. That is to say they had been sent to carry out some work but they needed a local person to show them around,” he said.

A young agent of the rank of constable was chosen as the “dog handler” for two reasons. His home area was Busia and, secondly, he had worked in Lugari before he was transferred to Eldoret. Therefore, he had a good knowledge of the region.

What happened after they left Eldoret, Mr Khwatenge said, was narrated to him by the constable whose code-name cannot be published for legal reasons.

They started by trailing him to Busia. Surprisingly, Mr Khwatenge said the agents did not make attempts to hide it from their victim that they were following him.

They hurled insults at the bishop and made middle finger gestures every time they overtook his car just to annoy him.

“It is called hostile surveillance, where you make somebody aware that he is being trailed then he becomes emotional and irrational,” Mr Khwatenge said.

When Bishop Muge was returning to Eldoret, they kept up with their harassment.

“All along, Bishop Muge knew he was being followed and he was looking for a way to shake them off.”

So, when he was approaching Kipkaren town towards Eldoret, he noticed a lorry ahead of him that was emitting thick smoke.

The ex-intelligence officer believes Bishop Muge wanted to overtake the lorry in the cover of the thick smoke, and then make good an escape.

For the bishop’s plan to work, he had to wait for an oncoming vehicle, preferably a trailer and then make the manoeuvre – to overtake the smoke-emitting lorry at high speed and get back to his lane just before the oncoming one approaches to delay his tormentors from overtaking.

“After Bishop Muge crashed his vehicle, the man who was in charge of the operation from Nairobi came out of their vehicle and ordered the rest to stay behind. He went straight to Muge’s damaged vehicle and only God knows what he did there,” said Mr Khwatenge. “When he came back, he took a powerful communication gadget to call Nairobi and said, ‘Operation Shika Msumari successfully completed’. It meant the bishop had been pushed to his own death.”

But the death of Bishop Muge shook the country and galvanised the proponents of multipartyism to carry on with their struggle.

There was no independent confirmation of the claims by Khwatenge, which are likely to be investigated by the TJRC, to which he has submitted a statement. The commission confirmed that it had received his forms.

Police charged the lorry driver who was driving on his lane at the time of the accident with dangerous driving. He was also charged with stealing school milk after several cartons were discovered in the lorry. He later died in prison.

Mr Khwatenge says he has approached the Kiplagat team and filled the forms some four weeks ago. Mr Wafula Buke, who is now a statement taker with the commission, handed him the forms.

Prodded him

Afterwards, a friend he did not name approached him and prodded him to apply for a job as a statement taker at the commission, but he declined because he believes had he got the job, he would be unable to testify as a witness.

Witnesses and victims give highlights of their testimony only in those forms to help the commission determine which witnesses they should call. According to Mr Khwatenge, he filled both as a victim and witness and is waiting for a call from the commission to testify.

TJRC’s communication director Kathleen Openda said they have yet to call Mr Khwatenge or any of those who have expressed their intentions to testify because the process of statement taking is still ongoing.

“We shall only call people after investigations and verification by the commission of the statements we have received. Right now, everything we have are claims and allegations that have to be investigated and verified before acting on them,” said Ms Openda.

Statement taking and verification is a five-month process that will then form the content for hearings set to begin in January 2011.

The commission has said that at the end of September they expect to have received 6,000 statements.