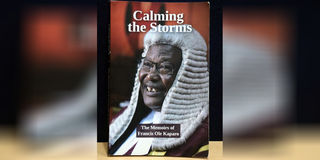

Former National Assembly Speaker Francis Ole Kaparo.

In 1991, President Moi appointed me the Minister for Industry. For the first time, I was to hold an office that was going to affect the lives of millions of people in the nation. It was humbling indeed!

When I was appointed Minister for Industry, I viewed that as a great honour. It was the culmination of an unlikely journey that started when colonial authorities plucked me out of my village and forced me into school. My rise had been meteoric.

As the Minister for Industry, I knew I wasn’t the most suitable man to handle the docket. I was also aware that I wasn’t the most qualified, but I was ready and willing to try my best.

So, when I accepted the job, I was aware that I was to act within the culture of top-down decision-making. It was my role to see how to engage the top so that my vision and dreams for Kenya were felt further down.

By now I had evolved into a realist because I already knew that the issues facing us had to run the gauntlet of public opinion, both at home and abroad.

In particular, my elevation to a full Cabinet ministerial portfolio was occasioned by international pressure on President Moi to relieve honourable Nicholas Biwott of his duties, pending investigations into the murder of Foreign Affairs Minister, Dr Robert Ouko.

Hon Biwott’s name had been adversely mentioned in connection with the Ouko murder by sleuths from Scotland Yard, the Metropolitan Police Service in London.

As Minister for Industry, I was cast in a critical role that made me have to play a key part in championing that rise. The year was 1992. It was a difficult time for our country because foreign governments and global bodies had staked continued aid to Kenya on a return to multiparty democracy.

Sanctions were biting hard, reverberating throughout the fragile economy, and gravely affecting many aspects of economic and social life. Government programmes stalled and salaries ate up a chunk of monies hitherto reserved for development. Factories were closed.

The supply of goods to our supermarkets began to dwindle. We were either going to become a multiparty State, or Kenyans would remain mired in poverty as sanctions bit harder.

Calming the Storms book by former Speaker of the National Assembly Francis Ole Kaparo as pictured on April 19, 2024.

I had to hit the ground running. Given the pivotal role my ministry had to play in the regulation of foreign exchange and stabilisation of the manufacturing sector, I acquainted myself with the many regulations that guided Kenya’s industrial operations.

At that time, international sanctions made foreign exchange very scarce. As a result, all foreign money was kept in the hands of the Government, and banks could only give it out after approval from the Foreign Exchange Allocation Committee, which was set up for the purpose.

In fact, it was a crime to hold foreign currency without this approval: I recall one Member of Parliament from Central Province being jailed for flouting this law.

The system was quite restrictive. For any individual travelling abroad, the amount of forex they were permitted to take with them was recorded in their passport. On returning to Kenya, travellers had to declare how much they had spent, and any shortfall was remitted to the Central Bank.

Unsurprisingly, the allocation of foreign exchange became a hotbed for illicit deals, confirming the adage that the more licences, permissions and bits of paper that a business needs to operate, the more likely corruption is to flourish.

I recall that at the height of liberalisation, an interview was arranged in which either Hon George Saitoti or the Permanent Secretary for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Dr Sally Kosgei, was to answer questions from a BBC Swahili anchor – a young woman from Tanzania.

We were in Brussels as part of our whirlwind tour to drum up international support in the face of a debilitating drought back at home.

It was Professor Saitoti who said, ‘Here is the Minister for Industry,’ as he jovially handed me to the young woman, who smiled and delved right into the matter at hand – with impressive professionalism.

I cleared my throat.

She said, ‘Waziri, hauogopi kwamba mkifanya soko ya pesa za kigeni huru pesa zenu zote zitatoka nje?’(Are you not worried that after liberalisation of the foreign exchange market your nation’s money will be stashed abroad?).

‘Zingine zitaenda, zinginezitaingia! (Some will be stashed away; some will find its way in!)’ I said.

It turned out that I was right.

And because of liberalisation, we ceased to have the foreign exchange allocated to Kenyans travelling abroad indicated on their passports; and Kenyans no longer had to apply to have their profits made in ventures abroad allowed into Kenya.

Former Speaker Francis ole Kaparo.

We removed prohibitive restrictions on transferring large sums of money from Kenya to offshore accounts and from offshore accounts into Kenya, believing that as the economy got more stable, more money would be invested within than siphoned off to accounts in foreign lands.

*****

On the basis of my proximity to the seat of power, I felt the sudden danger that the designation as the Minister for Industry posed. I ran the risk of becoming proud, seeing myself as better than those who hadn’t made the cut into the Cabinet. I also sensed that being in the Cabinet exposed me to the danger of engaging in corrupt dealings.

I knew this because the budget that went with my portfolio wasn’t a small one. Another danger I faced was that of becoming a sycophant. Still trapped in the transition trends between African patriarchies and participatory democracy, most public officials in Kenya held their offices at the whim of the Head of State.

Within this restricted context, open sycophancy became not just a reliable survival stratagem, but an ingrained philosophy in governance. Those who survived in the Cabinet or any other appointive office were the men and women who acted within the narrow framework of sycophancy.

They were the cunning state officials who knew that all decisions were made at the top, and that they were merely there to implement them.

Given my nature, I oftentimes found myself at odds with this approach. I wanted to be left alone to manage my ministry, to be freed to hire the best brains so that innovation would lead to greater growth and a better life for Kenyans.

I thus thought about the matter and felt that there had to be a way to handle it safely. I was going to play both hands at once – open sycophancy and demonstrable pragmatism.

I was going to be compliant when the stakes were low, a pragmatist when the stakes were high. I wasn’t willing to buy into the prevailing chorus of the time – that the only way to survive in the system was to become a reliable sycophant.

I had been around the Head of State long enough by now to realise that the man valued transformative opinions and was always willing to listen to whoever had great ideas. What he found unacceptable was acting contrary to decisions once they were made. It was all about collective responsibility.

I don’t know how historians will judge my tenure at Industry, but I know that I gave it my all within the framework of existing space for action. In spite of the unwritten rule requiring all government officials to be at public events officiated by the Head of State, I found time to sit, think and formulate strategies for the ministry. I understood that in those turbulent years my role was to be a trendsetter, to lay a firm foundation upon which future players in Kenya’s growth would anchor their new strategies.

*****

My public profile has often led people to assume that I was particularly close to Moi. I was not. In fact, I refused to praise him unconditionally, and this, together with my reputation for stubbornness, earned a measure of admiration from him. It is a matter of record that he promoted me from Assistant Minister to Minister in December 1991, just three days after I had taken my stand for multipartyism at Kasarani, when all around me were convinced that my political career was finished.

I do remember Moi as a hard worker, starting his day at five in the morning, and he had a talent for putting people at their ease when they were meeting him for the first time. Despite the manner in which he was often portrayed in the media, my personal experience was that he was an excellent listener, who paid due respect to those who were prepared to stand up to him.

At the same time, Moi was surrounded by acolytes who relentlessly misinformed him, telling him what they thought he wanted to hear, rather than any semblance of the truth, on many occasions. This was partly a situation that he brought on himself, having acquired a reputation for dishing out large sums of cash and parcels of land to those who pledged their loyalty to him.

He could even entertain conflicting factions simultaneously, though none would be aware that their adversaries also had his ear. Each would leave Moi’s company with a consignment of cash, without knowing that his political enemies were being treated in exactly the same manner.

They would then sing his praises at public gatherings, thinking unwittingly that they had been singled out for special treatment. This kind of behaviour will doubtless earn Moi a chequered reputation in the annals of history.

*****

Tomorrow: The one year that I worked as the Minister for Industry turned out to be one of the most inspiring of my life. It also marked the end of my five years as a Member of Parliament for Laikipia East, because I lost the next election in a Democratic Party wave in which a KANU candidate stood no chance.