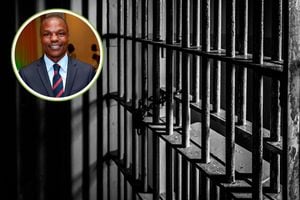

Police officers arrest a protester on Kenyatta Avenue in Nairobi during anti-Finance Bill protests on June 27, 2024. (Inset) Gabriel guda who was abducted and detained for two days.

In this second and final part of his harrowing story of abduction, media personality Gabriel Oguda writes about the night he was grabbed from his Nairobi house by police officers, questioned about his role in the anti-tax protests and driven around the city before being locked up incommunicado at Kajiado police station.

Monday, June 24, 2024 was the deciding day for teams in Group B at the Euros. Italy – whose football team I have supported since the England golden generation of 2006 left me with a bandaged heart – had just risen from the dead via a 98th-minute equaliser which was, it later turned out, the last kick of the game in the tournament hosted by Germany.

I was downstairs celebrating my team’s extended shelf-life when my gate started vibrating. At first, I thought it was one of my neighbours who has the notorious habit of announcing his arrival with a blast from his car that should be licensed by the National Environment Management Authority as a mobile disco.

But the commotion at my gate was not that of rough music from a coughing Datsun. Before long, the light-sleeping daughter of Rarieda was halfway down the stairs in panic, relaying the news of the arrival of police officers.

Kenyan police are not good people. In 2017, a global security index rated them the third worst in the world.

Mr Japhet Koome, the Nairobi County Police Commander at the time of the ranking, accused the study of colluding with enemies of Kenya. He is now the Inspector-General of Police.

Extra-judicial

When his officers started breaking down my gate around 1.40am on Tuesday, I knew my turn at being an extra-judicial statistic had finally arrived.

What could have been a routine visit for them to join me in celebrating the Italy win quickly degenerated into a terrorist hunt.

Columns of menacing armed plainclothes officers combed every blade of grass in my compound, digging for a bomb they claimed was hidden in my house, only to later discover they were looking for Twitter. Being the law-abiding citizen that the Catholic Church trained me to be, I handed over my phone. Not long after that, I was floating out of my compound to the world unknown.

Before this military shakedown at my house, I had read stories about a rogue unit in the National Police Service Police whose main job description was to pick you up and take you to God.

As I was being manhandled into the back seat of the Subaru Outback, which was third in the convoy of five that had blocked the driveway into our court, I made peace with my maker and closed my eyes waiting for the killer shot.

It did not come. Instead, they revved the engines, leaving my neighbourhood in a whirlwind of dust, driving me like contraband goods that were late for the underground market. After greeting me in the name of the government “that you are pricking with a needle”, the two men – who sandwiched me in the backseat – asked questions “to test the hardness of your head”.

“Are you a Gen-Z?” they prodded.

Are you for real? You mean, there are people in this country who wake up in the morning telling their children they’re going to work only to end up dispensing a questionnaire on someone they have not conducted a background check on? What wisdom is that?

I answered in the negative. In such circumstances, I could not afford to lecture my kidnappers on what it means to have a job – any job – in a country where half the population lives by God’s grace.

The rest of the interrogation revolved around my daily bread, weekly hobbies and monthly pay. They also queried me on how long I had lived in Nairobi, my level of education, my family status, and whether I had received any Roubles for the printing of “Occupy Parliament” protest merchandise.

Interrogation

All through the interrogation, I stuck to one-word responses in respect of their time and fear for my life. But when it came to my education status, I thought about reminding them that I went to Maseno School, only for the guy to my left to squeeze a pistol on my tummy as he was adjusting his sitting position, and I was back to reality.

The breakneck tour of the city finally came to an abrupt stop at that dark chicane that connects Outering Road with Airport North Road.

Unknown to me, alarm bells had been raised about my mysterious kidnapping and response teams had started using technology to track my phone and give chase. This is the point I knew these guys might actually have gone to school to a level past Oscar Sudi.

They yanked me out of the Subaru Outback, had me standing in the middle of the road for a mugshot using their mobile phones. When one minute of fame was over, they shuffled me into the backseat of a Ford Ranger double cabin pick-up that had been part of my security detail.

The Subaru teams fell out and took another route as a decoy to those tracking my phone and giving chase. Off we set out with the double cab to Kajiado town.

I arrived at Kajiado police station way past my elastic limit of endurance and with a glimmer of survival barely flickering.

The team of five dumped me at the Occurrence Book desk with instructions for the officers to book me into the cells incognito. It was not the destiny I had asked for, but in life, you play the cards that you’re dealt.

Getting locked up at Kajiado police station was not the first time I had been a guest of the state.

In early 2002 as I was waiting for my KCSE examination results, my friend Robert and I set out to Miwani Division headquarters in Masogo-Nyang’oma Ward, Muhoroni Constituency, to meet the National Registration Bureau (NRB) team from Kisumu who had come to assist us register for national identity cards.

I had this black T-shirt with teenage mutant ninja turtles’ graphics emblazoned in front that made me feel like part-man part-jaguar.

The restless group of young men and women who had been sweltering in the sun as they waited for the NRB folks to arrive might have noticed my high energy levels and decided to nominate me to be the person who would walk up to the District Officer and inform him that had he wanted to boil us in the sun, he shouldn’t have hidden behind a national ID card registration drive.

You should have seen me with a spring in my steps bouncing, only to be stopped by the Administration Police officers at the entrance who asked where I thought I was going. I looked over my shoulders to see if the mob was still with me to represent their interests. When I saw fists in the air, I knew that was my licence to turbo-charge.

In hindsight, I should have chewed gum first before scaling the stairs. The next thing I knew, I was inside the juvenile holding cells at Masogo Police Station asking my new cell mates if they knew who had taken my shoes and belt.

Kajiado police station has a female officer who doubles up as the resident chaplain. Her job is to conduct prayers for those going to court with the intention of numbing them into taking the sentence that is coming as God’s will.

I have never seen anything like that before. I asked my two cell mates that Tuesday morning whether they felt any impact of the woman’s spiritual session. They were categorical that it was the highest form of government idleness.

Constant conflict

This country is in constant conflict with young people because those who make decisions on their behalf live in a parallel universe. There is no way you are going to pacify an agitated group suffering police injustice by pumping Bible verses into their bloodstream. I asked the two boys you read their story in yesterday’s Saturday Nation if they would consider turning to Christ if they were to be found guilty of the crimes placed before them. You should have heard the sacrilegious curses in the room.

These young people staring down the barrel of the gun are not your typical Kenyan youth who were weaned on the Daniel Toroitich arap Moi tyranny and trembled in fear in the presence of authority. The Gen-Zs are not only built different, they’re built to last.

The young men who filled my cell from the crackdown in Kajiado town Tuesday afternoon told me that if there is no fast intervention in a way that pleases the Lord, the demonstrations would cease being about the Finance Bill, 2024 and include all the historical injustices young people have suffered in Kenya.

I have told you what I was told. In the immortal words of a certain roots reggae philosopher: “You can kill the messenger but you can never kill the message.”