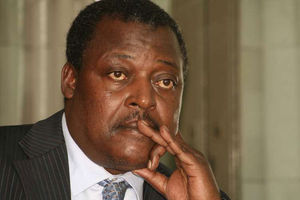

Cyrus Jirongo during an interview at his Mayfair Suites offices in Nairobi on October 28, 2021.

Fifty days after President Moi was sworn in for another term on January 4, 1993, the powerful Youth for Kanu ’92 chairman Cyrus Jirongo walked into the National Social Security Fund (NSSF) headquarters to force through a deal. It was a Tuesday, February 23, 1993 and hubris had set in.

In the corridors of power, Jirongo moved with the easy authority of a man honed by the campaign trail. He had chase cars and security. He had become fluent in a lesson Kenya often reserved for its quickest learners: influence was currency, and he knew precisely how to spend it.

Weeks earlier, before he entered the NSSF boardroom, Jirongo had steered a polished, well-heeled campaign machine—one that quickly elevated him into the inner sanctum of the ruling party, Kanu. In the wake of Kanu’s controversial victory, the hour had turned in Jirongo’s favour: this was his moment to harvest the dividends of politics… and to collect what power had promised: money.

For Jirongo, the battlefield had changed from rallies to NSSF boardroom where he struck first. The deal he fronted through his Sololo Outlets Ltd, whose other chairman was Mombasa Kanu supremo Shariff Nassir, was both audacious and seductive. The idea was to turn two NSSF’s plots in Nairobi —LR No 209/9101 and LR No 209/9103—into a small republic of middle-class promise: 100 maisonettes, 320 flats, a nursery school and health centre, shops, a recreation complex, a primary school. The stated price for the entire vision was Sh1.2 billion, and Jirongo asked for 50 per cent payment, upfront.

Cyrus Jirongo during an interview at his Mayfair Suites offices in Nairobi on October 28, 2021.

For the money to move, a conduit had to be put in place. Jirongo turned to a trusted associate: Vihiga-born Francis Chahonyo, who headed the politically connected Post Bank Credit Ltd, another bank that YK’92 had previously used as a conduit. By then, Post Bank was widely viewed as one of the most abused banks in Kenya and had reportedly also been used by Kamlesh Patni’s Goldenberg International as a channel before he was allowed to run his own bank, Exchange Bank. Jirongo then signed a memorandum of understanding with Post Bank Credit to act as the disbursing agent for NSSF’s payments to Sololo.

When YK’92 functioned as a cash dispenser, Jirongo opened accounts for his companies—Cyperr Projects International and Cyperr Enterprises—at Post Bank Credit. He had also perfected the art of running up overdrafts. For instance, after Cyperr Projects opened an account in July 1992, it was, by April 1993, overdrawn by about Sh20.8 million.

But it was Sololo’s account—opened in September 1992, just three months before the general elections—that truly stood out. By May 31, 1993, its overdraft had soared to Sh1.686 billion, an exposure large enough to bring Post Bank to its knees.

How did it happen?

Post Bank had extended Sololo an overdraft facility of up to Sh1 billion, secured by a debenture dated March 23, 1993. The facility was also personally guaranteed by Jirongo and his new ally, Dr Davy Koech, who was linked to the controversial Kemron “HIV/AIDS drug” claims. In practical terms, Sololo exceeded the approved limit by an additional Sh686 million.

By then, NSSF had already paid Jirongo’s firm Sh500 million to kick-start the housing project. Yet even without delivering, Sololo wrote demanding payments far beyond the agreed consideration—and before completion—citing cost escalations following the devaluation of the shilling.

Banking on the promise that funds from the NSSF were imminent, Jirongo milked Post Bank with an ease that bordered on audacity. Flush with cash, he fashioned himself into a philanthropist, dispensing money to politicians and purchasing influence in the very act.

Beer parties became routine, harambees multiplied, and his office was never short of visitors. In Western Kenya, his name had become a byword; he was determined to bankroll the region’s politics and, by extension, its power.

Yet Jirongo nursed little warmth for Vice-President George Saitoti and Kanu Secretary-General Joseph Kamotho. He moved against them first, as Moi observed YK’92’s bid to manufacture a new class of power-brokers.

Unwilling to sacrifice loyal allies—or to risk the emergence of an alternative centre of authority—Moi chose instead to tighten the leash. In April 1993, with the NSSF scandal now public, he ordered the dissolution of YK’92 within a month, reining Jirongo in before the project could harden into a rival power base.

Former Member of Parliament for Lugari Constituency the late Cyrus Jirongo.

Buoyed by Jirongo’s fall from power and as Parliamentary watchdogs continued to put pressure on NSSF, the Fund’s managing trustee had, within weeks, on May 26, 1993, written to Jirongo seeking to end the agreement and demanded Sololo hand over the site and materials.

A week earlier, thanks to the cash dispensed to Jirongo and other politically-correct Kanu outfits, Post Bank had slid into statutory control. On May 20, 1993, the Deposit Protection Fund Board had appointed a statutory liquidator under section 35 of the Banking Act, tasked—according to the court record—with taking custody of the institution’s books and assets, recovering what was owed, and managing creditors and debtors under the High Court’s supervision.

Without political power, Jirongo found that the language of persuasion had given way to the language of enforcement.

On July 15, 1993, receiver-managers were appointed for Sololo and Cyperr Projects under the debentures’ powers. In commerce, that was the moment talks ended, and collection began.

And then—the twist.

By the time YK’92 was formally disbanded on June 12, 1993, Jirongo had managed to amass substantial funds from public land that could not be auctioned. Notably, YK’92 was never formally registered, meaning that Jirongo alone, rather than Moi or Kanu, bore responsibility for its excesses.

In public, the man associated with the ruling party’s electoral muscle had been useful; in the ledger books and court pleadings that followed, he was now simply a guarantor, a director, a signatory—someone whose influence no longer softened the edges of institutional power. The same political climate that had once turned his name into currency now changed, and he found himself negotiating not with crowds but with receivers, liquidators, trustees, and judges.

That was Jirongo’s life, post-YK’92. What followed was not merely a commercial dispute; it became an argument about the moral architecture of Kenya’s early multi-party era—how deals were made, how they were enforced, and who could credibly claim victim-hood when the machine turned.

In March 1994, eight months after receivership began, the companies and Jirongo sued. Their plaint accused NSSF, Post Bank, the statutory liquidator and the receivers of acting through threats, coercion and duress to procure mortgages, charges and debentures securing refund of money allegedly paid under the NSSF agreement.

The allegations were vivid, including claims of intimidation by CID officers at advocates’ offices linked to the Fund and Post Bank. Sololo admitted receiving Sh900 million via Post Bank, and insisted the project was 75 per cent complete. It said that the escalating costs had pushed the price to Sh2.5 billion—an amount it demanded and NSSF refused.

Mr Cyrus Jirongo who was the chairman of YK'92.

This was the hinge on which Jirongo’s public mythology and private paperwork swung. Sololo alleged that Post Bank sought to “convert” NSSF payments into a loan; it claimed the March 23, 1993 debenture was procured by misrepresentation and economic pressure; it accused NSSF of dispossessing it of the site and materials after termination.

Cyperr Enterprises, meanwhile, claimed trespass—saying the receivers seized its offices on the 16th floor of Anniversary Towers.

Jirongo fought many battles in court—some against men who borrowed from him and never looked back, others against partnerships and glittering deals that collapsed the moment the ink dried.

For years, the disputes came in waves, each one a reminder that money can move faster than trust, and that an empire built on handshakes can be shaken by a single broken promise.

Yet he was not a man who stayed in the shadows of his own troubles. He stepped into the arena of politics with the same audacity that had marked his rise, winning the Lugari seat in 1997 and, for a brief nine months in 2002, taking his place in Moi’s Cabinet. When the political shield that once softened blows was switched off, the hidden fractures in his architecture of debts and deals began to show. Jirongo lost his Lugari seat.

By 2017, the distance between legend and reality had grown painfully visible. He ran for the presidency and drew only 11,000 votes, an embarrassment for a man who once manufactured Kanu’s victory.

Then came October 2017: the High Court declared Jirongo bankrupt over a Sh700 million debt owed to businessman Sammy Kogo. The headlines did what headlines always do: they turned a complicated human story into a single cold word, a verdict that seemed to swallow everything that came before it.

And still, the Jirongo myth refused to die completely. To many, he remained the man of open hands and sudden generosity—the philanthropic figure who could walk into a bar and walk out after cash rounds, entertaining friends, acquaintances, and strangers alike, as if joy itself were something he could purchase in bulk and distribute on impulse. It was a kind of theatre, yes—but also, for those who benefited, a kind of grace: the charisma of a man who gave as though tomorrow was guaranteed.

In the end, his story reads like a hard Kenyan parable about the volatility of power and the illusion of permanence. He was a man remembered for the money he spread, the doors he opened, and the boldness with which he lived. But at the end of it, he was part of a scheme that took money meant for pensioners.

Follow our WhatsApp channel for breaking news updates and more stories like this