The people's lawyer who rewrote Kenya's family laws

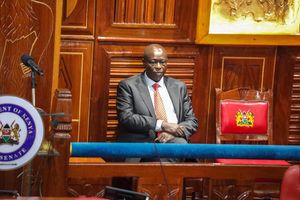

Judy Thongori who was a senior counsel and family lawyer during an interview on September 4, 2024 at her office in Westlands Nairobi.

What you need to know:

- Kenya's legal landscape has lost Judy Thongori, a pioneering family lawyer who was instrumental in crafting transformative legislation.

- As deputy executive director of Fida-K and later as an independent advocate, she championed women's and children's rights, helping outlaw underage marriage, protect women's property rights, and combat harmful traditional practices.

- Beyond her professional excellence, Judy was remembered as an exceptional human being known for her compassion and approachability.

News of the demise of Judy Thongori on Tuesday, January 14, landed like a thunder bolt – sudden, vicious, hot, pulverising, paralysing and destructive, yet final. The immediate feeling was that of disbelief, dullness, anger and helplessness. How could this happen just when Kenya was still moaning two other illustrious women – Roselyne Odede, chair of the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights, and Rasna Warah, the indefatigable former Nation columnist who stood for truth even if it cost her a living?

Judy Wanjeri Thongori was famously referred to as a family lawyer, in recognition of her specialisation on this branch of law. The phrase “family laws” refers to legislation focusing on marital issues, ownership of and succession to property and relationships within the domestic sphere. Three of these laws – the Matrimonial Property Act, Marriage Act and Protection against Domestic Violence Act - were passed by the 11th Parliament in quick succession, bolstered by an increased number of women in the legislature due to affirmative action and an optimistic transformative environment following promulgation of a new constitution in 2010.

Notably, Judy was one of the architects of these laws, working in the background to fine tune them and strategising with female legislators on how to ensure their passage. The main gains in these laws are: protection of girls from under-age marriage; equal recognition of women in monogamous and polygamous unions; mandatory registration of all except Muslim marriages; spousal individual rights to pre- nuptial property; and inclusion of harmful traditional practices in the definition of domestic violence.

Collectively, the laws create a legal framework under which various gender inequalities can be prosecuted.

From her position as the Deputy Executive Director and Head of Litigation at the Federation of Women Lawyers Kenya (Fida) in the late 1990s, to her practice as an independent advocate, Judy stood out as not only a passionate advocate of women’s and children’s rights, but also a compassionate one. When she spoke about these matters, it was clear that she was not merely doing a job but was on a mission to change the world for the better. Thus, it was quite apt for a local TV station to refer to her as “the people’s lawyer”, because transforming women’s and children’s lives is improving the whole society.

Judy constantly confessed that exposure to gender awareness, in which this writer paid an instrumental role for Fida, was catalytic in transforming lawyers from mechanistic to activist practitioners. Professional colleagues who benefitted from the same include Anne Amadi (former Chief Registrar of the Judiciary), Judy Sijeny, Justice Njoki Ndungu and Justice Fatuma Sichale.

She co-authored World Bank’s Gender and economic growth in Kenya: Unleashing the power of women (2007), which looked at Kenya’s legal framework in relation to gender equality before examining: the gender-economic growth nexus; access to property, finance, collateral, formal sector- business entry and licensing and justice; and the impact and opportunities of international trade and labour. The gist of the publication was that although Kenyan women were making enormous contributions to economic growth and development, they were shackled by multiple gender-related challenges.

In “Overview of Kenya’s legal framework”, which Judy must have contributed to, the book identified discriminatory elements in the Law of Succession Act, Children’s Act, divorce laws and customary laws. Many of these were subsequently addressed in the family laws passed in the 2013 – 2015 period, as well as the 2020 Constitution. She wrote a chapter titled “Constitutionalisation of women’s rights in Kenya” in Gender gaps in our constitutions, published by Heinrich Boell Foundation in 2002. The book explores the then constitutional gender issues from South Africa, Zimbabwe, Somaliland, Southern Sudan, Northern Sudan, Uganda, Ethiopia and Kenya. Judy also penned a column on family law in the Daily Nation, albeit for a short period.

During the first scientific conference of the Kenyatta University Women’s Economic Empowerment Hub in 2023, Judy made a pitch for making the family the hub around which to tackle gender based violence. She argued, rightly, that data persistently identifies the family as the locus of majority cases of violence, especially by intimate partners.

Judy is one person you cannot begrudge the honours she received: induction into the Law Society of Kenya’s (LSK) Roll of Honour – 2013 (first female Kenyan lawyer); LSK award for pro-bono legal services – 2015; and conferment of the coveted title of Senior Counsel - 2020.

If reincarnation is true, it should recycle Judy immediately. Needless to say, her name deserves to be immortalised in institutional and state honours, as well as in names of public infrastructural assets. Beyond her legal excellence, Judy was simply an exceptional human being – affable, unassuming, approachable, friendly, sociable and ready to listen and assist. Shame on death.

The writer is a lecturer in Gender and Development Studies at South Eastern Kenya ([email protected]).