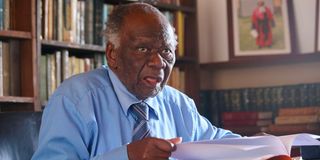

Senior Counsel John Khaminwa during an interview at his Kileleshwa home in Nairobi on September 9, 2023.

| Wilfred Nyangaresi | Nation Media GroupNews

Premium

John Khaminwa: My 53 years as a lawyer and why I don't own a smartphone

When senior counsel John Khaminwa turned 87 years old on September 10, he mostly thought about the dark cloud of death that had hung over his family, his previous struggles in colonial days, and his life ahead.

For a man who lost his wife, Joyce Khaminwa, just two years shy of celebrating 50 years of marriage in 2014 and his elder son Albert Khaminwa in 2017 then a brother soon after, he says the pain never fades away.

But none of these occasions compares to his experiences in July 1990 when he says he missed death by a whisker. The country was gearing up for Saba Saba Day when Kenneth Matiba and Charles Rubia were arrested on the eve of the rally. A meeting at the home of then Shinyalu MP Japheth Shamalla resolved that Mr Khaminwa and Mr Shamalla would go to the police to seek the whereabouts of the two and plead for their release.

When they arrived at Nairobi Area Police Station (now Traffic Police Headquarters, Upperhill), they were received by a pleasant police inspector who offered them tea and invited them into a lounge. The meeting would later turn out to be a big trap.

“He told me there was something very private he wanted to share with me. I insisted that my colleague Mr Shamalla should also accompany me but he said that I should just go with him and I followed him. He led me through a door that had remained closed to a room where I saw a long line of police officers who were armed to teeth,”Mr Khaminwa recounts. He was ordered to walk between the officers and turn around to face the inspector after a few steps.

“He looked at me, smiled and said: Khaminwa you have been detained!”

He was taken to a cell and stripped naked. The room was half-filled with cold water. He stood there up to past midnight.

“They came into the room past midnight, gave me clothes, blindfolded me and led me to a police car,” he recalls.

The police car came to an abrupt stop and he was ordered out. He noticed that they were in the dense Karura Forest. As he was led into the forest, all he could do was pray.

“I prayed to God and told him: You gave me life, please do not take it away. I ask you, God, please let me not die this way,” the octogenarian says. Suddenly, the officers had a change of heart and ordered him to get back into their vehicle. He was taken to Kamiti Prison in Nairobi, kept in solitary confinement for about three weeks and later released thanks to the international development partners who threatened to withdraw their aid if President Moi did not release political detainees.

Recalling the incident, Mr Khaminwa says his strong beliefs and the short prayer carried the day. A Quaker by faith, Mr Khaminwa was born in 1936 in Western. His father Ralph Asiabugwa Khaminwa was a primary school teacher while his mother Rasoah Muhonjia Khaminwa was a housewife.

It was his parents who encouraged him to study hard. He attended Masiyenze Primary School in Ikolomani, Musingu Intermediate School, Alliance High School, Makerere University and Dar es Salaam University where he graduated with a bachelors degree in law. He would later pursue a masters degree in international law at the New York University in the United States and an external bachelor’s law degree at the University of London.

His career in law has seen him serve as State counsel, a magistrate, and a deputy registrar of the judiciary. He would, in 1968, cross over to Uganda where he served as the principal legal assistant of the East Africa Community (EAC) and rose to the position of deputy counsel. His wife also served as registrar of the East Africa Industrial Court. In 1970, Mr Khaminwa was admitted to the bar. He worked at the EAC for four years.

The events of September 1972 during which then Uganda Chief Justice Benedicto Kiwanuka was shot in Makindye Military Prison in Kampala for releasing British businessman Daniel Steward who had been detained by the Ugandan military allegedly on the orders of President Idi Amin turned his life upside down.

“Lawyers were being killed and the moment I saw that the chief justice was killed, I knew things were not well. I had to make a quick decision lest the same fate befall me,” Mr Khaminwa says.

A few days later, Mr Khaminwa resigned from the EAC. His wife also followed suit. In Kenya, President Jomo Kenyatta and those around him were tightening their grip on power.

Lawyers in the country were cautious about the cases they were handling. Mr Khaminwa explains that lawyers during those days dealt with common law issues such as contractual and commercial matters.

“They avoided cases that put them on a collision course with the government,” he says.

Senior Counsel John Khaminwa during an interview at his Kileleshwa home in Nairobi on September 9, 2023.

At the time, judicial officers were usually of Asian and European origin and only a few Africans were practicing law. It wasn’t until a few years later that Kenya had its first black resident magistrate, Mr Sibi Okumu.

Mr Khaminwa recalls that the circumstances surrounding his appointment were also special. A black American man was arraigned before the chief magistrate who was white but the suspect protested, saying that there was no way a white man would hear his case in a black country. This made President Kenyatta intervene and Mr Okumu was picked from the AG’s office and sworn in as the first black resident magistrate in the country.

As a barrister, the next thing he thought after landing in the country was establishing his private practice.

Together with his wife, they established Khaminwa and Khaminwa Advocates in 1974. The law firm specialised in constitutional matters. His policy was to represent anyone who came to the law firm for assistance. The aspect of representing “everyone” did not sit well with government mandarins.

In contrast to Mzee Kenyatta’s reign, Mr Khaminwa says President Daniel Moi, his successor from August 1978, was very sensitive and chose to deal with dissidents directly.

As he reflects on his 87 years of life, Mr Khaminwa says that the death of his wife, son and his brother Charles Forde left a big wound in his life. But this has not stopped him from working. His office in Lavington is a beehive of activity. Always donning a trench coat and a black hat, Mr Khaminwa together with his team of researchers are always busy. .

At his office, there are also a few electronic gadgets and it is for a good reason. One expects Mr Khaminwa to own flashy gadgets or vehicles but he has maintained a moderate lifestyle.

Senior Counsel Dr John Khaminwa in his office along Gitanga Road in Nairobi on December 1, 2020.

He owns a basic feature phone and has always avoided owning smartphones in his life.

“It is a personal decision that I decided not to own a smartphone,” Mr Khaminwa says.

He also recalls that, in the 1980s and during subsequent years, the government would try to monitor conversations of human rights activists and they were kept under police surveillance all the time.

This is one of the reasons he is keen and occasionally requests us to pause the recorder when he wants to mention something that he does not wish to be recorded.

Reflecting on the current judiciary, Mr Khaminwa insists that endless criticism of the judiciary by those in power is not doing the country any good as it erodes the confidence of investors and citizens. “It is better for us to have a judiciary with shortcomings that can be corrected privately than to have a judiciary without confidence, the alternative is chaos,” he adds.