Kenya-Somalia maritime border.

| Joe Ngari | Nation Media GroupNews

Premium

Kenya to take Somalia border row case to UN Security Council

Kenya will today (Monday) inform the International Court of Justice (ICJ) of its withdrawal from the case on boundary dispute with Somalia citing bias, the next action being a protest to the United Nations Security Council (UNSC).

The Kenyan government, which has objected to virtual proceedings, has asked the court to allow Attorney General Kihara Kariuki a 30-minute address to express its displeasure with the court’s conduct, before public hearings in the Indian Ocean boundary dispute between the neighbouring countries begin today.

And in a dramatic escalation of Kenya’s relations with the ICJ, which is reminiscent of its fall-out with the International Criminal Court years back when Kenyan leaders were on trial, the government has vowed “complete divorce” with The Hague-based court if its grievances are not addressed today.

“Whether they refuse to admit the request or grant it, we have reached tipping point, a point of no return. If you like, the irreducible minimum is for us to be granted time to complete our preparations with our new (defence) team and to present our case in normal conditions of physical appearance where we can put across our case without hindrance. A token, cosmetic appearance won’t do for Kenya,” a highly-placed Kenyan official told Nation yesterday.

And signalling Kenya will resort to drastic action to question the credibility of the court, triggering a diplomatic crisis, the official added: “I don’t see the court acceding to our request and as such it’s fair to conclude that tomorrow we are headed for complete divorce with that court.”

Boundary dispute

Asked Kenya’s next course of action given it’s a non-permanent member of the UN Security Council, and it has in the past portrayed the boundary dispute as a threat to regional security, the official revealed Nairobi will this week petition the global body tasked with maintenance of international peace and security.

“For now it would be interesting to see how the court handles the dispute. But in the meantime we remain fully seized of the matter and starting this week we shall be notifying the UN Security Council of the transgressions that Kenya has faced before that court and the danger the court’s cavalier attitude poses to security in the Horn of Africa. Our statement shall also be circulated widely through diplomatic channels worldwide,” the official disclosed.

In a letter on March 11 communicating Kenya’s decision not to participate in today’s hearings, the government cited judges’ disregard of all its applications— including the recent postponement of proceedings as Covid-19 pandemic had disrupted preparations by its newly appointed legal team and the shortcomings of presenting its complex case virtually.

“Kenya regrets that it has been compelled to take this step- unprecedented in its history in relation to any international adjudication mechanism- because of the unwillingness of the court to afford it a fair opportunity to prepare for and to present its case,” the AG wrote in the letter addressed to the court’s registrar Philippe Gautier.

“Since the case herein is not urgent for any reason, Kenya least expected the court would make this into the first case to be heard on the merits via video link, despite one party’s sustained and well-grounded objections,” the letter adds.

Kenya contends online proceedings favour Somalia whose case is not dependent on complex demonstrations and that Kenya has more than four critical members, above the number each party is allowed into the courtroom, who are all in the age bracket at greater risk of Covid-19 hence unable to travel to The Hague.

The disregard of these concerns, alongside previous “inexplicable” rejections of its preliminary objections to the court’s jurisdiction and the dismissal of the request for the recusal of Judge Ahmed Yusuf, a Somali national, have fueled Kenya’s perception of “unfairness and injustice in this matter.”

The case concerning maritime delimitation in the Indian Ocean will open at 3pm at the Peace Palace in The Hague, the seat of the court.

Kenya lost its quest to have proceedings of the long running dispute postponed, with the court directing the public hearings run from Monday to Wednesday, March 24.

Given the Covid-19 pandemic, the hearings will be held in hybrid format— in-person appearance and virtually.

“Some members of the court will attend the oral proceedings in person in the Great Hall of Justice, while others will participate remotely by video link. Representatives of the parties to the case will participate either in person or by video link,” the court directed in a statement that releases the schedule of the hearings.

The dispute

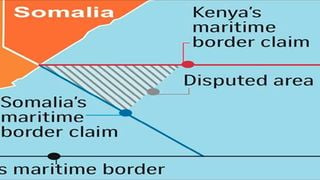

As adjacent coastal States facing generally south southeast onto the Indian Ocean, the potential maritime entitlements of Somalia and Kenya overlap, including in the area beyond 200 nautical miles.

The parties disagree about the location of the maritime boundary in the area where their maritime entitlements overlap, according to court records.

Somalia, which filed the case in 2014, argues the maritime boundary between the parties in the territorial sea, exclusive economic zone (EEZ) and continental shelf should be determined in accordance with the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) Articles 15, 74 and 83, respectively.

Article 15 of UNCLOS states: “Where the coasts of two States are opposite or adjacent to each other, neither of the two States is entitled, failing agreement between them to the contrary, to extend its territorial sea beyond the median line every point of which is equidistant from the nearest points on the baselines from which the breadth of the territorial seas of each of the two States is measured.”

But there is a rider. “The above provision does not apply, however, where it is necessary by reason of historic title or other special circumstances to delimit the territorial seas of the two States in a way which is at variance therewith.”

Article 74 states: “The delimitation of the exclusive economic zone between States with opposite or adjacent coasts shall be effected by agreement on the basis of international law, as referred to in Article 38 of the Statute of the International Court of Justice, in order to achieve an equitable solution.”

The same provision applies under Article 83 with respect to the delimitation of the continental shelf.

In both instances, the Articles provide where there is an agreement in force between the States concerned, questions relating to the delimitation of both the EEZ and continental shelf shall be determined in accordance with the provisions of that agreement.

Somalia’s argument is based on the use of the equidistance principle as the method of determining states’ maritime boundaries.

Accordingly, Somalia argues, in the territorial sea, the boundary should be a median line since there are no special circumstances that would justify departure from such a line.

In the EEZ and continental shelf, Somalia contends, the boundary should be established according to the three step process that the court has consistently employed in its application of Articles 74 and 83.

But Kenya’s case is that a boundary along the parallel of latitude has developed through the consent of Somalia since 1979.

Since Somalia never protested for that long, Kenya contends that a boundary was established by a tacit agreement between the two states.

Accordingly, Kenya’s position on the maritime boundary is that it should be a straight line emanating from the States’ land boundary terminus, and extending due east along the parallel of latitude on which the land boundary terminus sits, through the full extent of the territorial sea, EEZ and continental shelf, including the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles.

Kenya measures the breadth of its territorial sea and EEZ from a series of straight baselines covering the full length of its coast.

These baselines were first declared in the 1972 Territorial Waters Act and have been amended from time to time.

Somalia considers that Kenya’s straight baselines do not conform to the requirements of UNCLOS

Kenya’s submission to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS) is that the outer limit of its continental shelf lies fully 350m from its coast.

Somalia has since 1979 respected the maritime boundary between the two countries along a parallel of latitude.

However, in 2014, shortly before filing its case with the Court, Somalia claimed a maritime boundary along an equidistance line, ignoring the 35-year practice of recognising the maritime boundary along a parallel of latitude.

Kenya asserts that all her activities including naval patrols, fishery, marine and scientific research as well as oil and gas exploration are within the maritime boundary established by Kenya and respected by both parties since 1979.

Court decision

The court will determine, on the basis of international law, the complete course of the single maritime boundary dividing all the maritime areas appertaining to Somalia and to Kenya in the Indian Ocean, including in the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles.

Also, judges will determine the precise geographical coordinates of the single maritime boundary in the Indian Ocean.

The case resumes with Judge Joan Donoghue from the United States as the president of the ICJ.

She was elected in February to replace Judge Ahmed Yusuf, a Somali, who has been at the helm of the court since 2018.

Others judges are Yusuf, Peter Tomka (Slovakia), Ronny Abraham (France), Mohamed Bennouna (Morocco), Antônio Augusto (Brazil), Xue Hanqin (China), Julia Sebutinde (Uganda), Dalveer Bhandari (India), Patrick Robinson (Jamaica), James Crawford (Australia) Nawaf Salam (Lebanon), Iwasawa Yuji (Japan) and Georg Nolte (Germany).

Kenya had applied for postponement of the case citing Covid-19 pandemic disruption to its preparations but the court rejected the application.

Kenya had argued its new legal team, recruited in January last year, has faced difficulties since the pandemic struck the country in March, last year, as travel bans stopped its foreign lawyers from meeting their local counterparts and also hampered efforts to collect material evidence.

Another concern by the Kenyan government was about a missing document authorities say is critical to Kenya’s case.

“While the adverse effect of the pandemic has occasioned Kenya’s inability to access this document and other additional material evidence that it hoped to secure for presentation to the court in advance of hearing, Kenya has nevertheless gathered significant evidence, which it wishes to present to the court,” Attorney-General Kihara Kariuki wrote in the letter dated January 28 addressed to Mr Philippe Gautier, the court’s registrar.

Schedule for the hearings:

First round of oral argument

Monday 15 March — 3pm-6pm (Somalia)

Tuesday 16 March — 3 pm-4.30pm (Somalia)

Thursday 18 March — 3pm-6pm (Kenya)

Friday 19 March — 3pm-4.30pm (Kenya)

Second round of oral argument

Monday 22 March — 3pm-6pm (Somalia)

Wednesday 24 March — 3pm-6pm (Kenya)